plants, steel plants all the way up the

middle of the city. W hile they’re trying

to clean it up now, for years they dumped

raw sewerage into the river. T hat will

always do away with us quicker than the

marketing. T here are enough local sales

here that you’d probably get by with.

Sometimes, we get a little bit better than

market price. I’m afraid there’s just not

going to be any more shrimp.”

A side from pollution, over-fishing has

also proved problematic. Y ears ago, C ape

Fear and other sensitive areas were closed

early in the season to allow developing

shrimp to grow. N ow, G eorge says, closures

are rare and too many commercial and recreational

shrimpers don’t use discretion in

the all-important nursery areas. T he shrimp

46

WBM october 2011

are caught before they can continue the

cycle; much less grow big enough to sell.

G eorge says that while he used to

debunk the disappearing shrimp theory that

G alloway spoke of as a glorified myth, after

years of watching the shrimp size and count

dwindle, he’s now willing to wager that in

ten years there will be no shrimp to be had

in this area.

Potter is more optimistic. “Shrimp can

lay up to 250,000 eggs every three days and

they have a life span of twelve to eighteen

months. T hey reproduce so fast and with

such volume that I’d say they are pretty

resilient.”

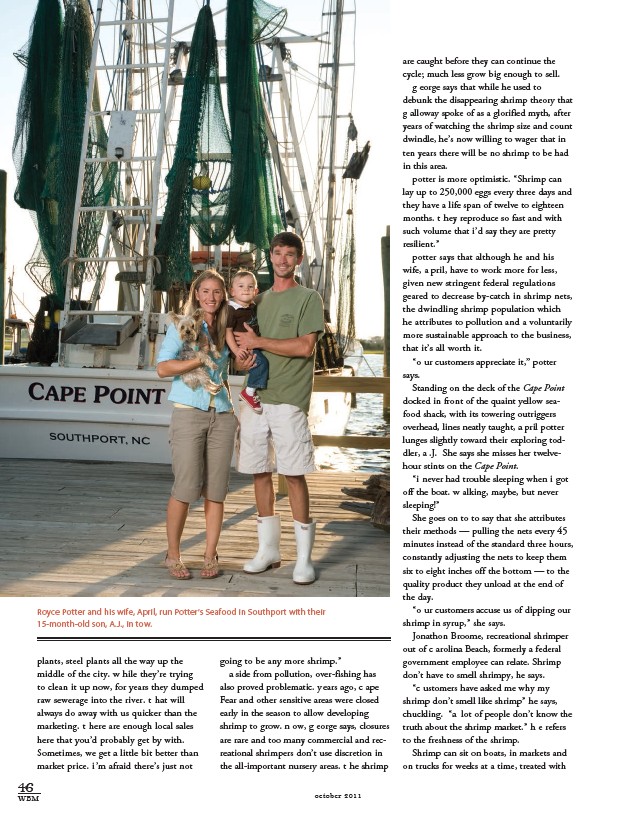

Potter says that although he and his

wife, A pril, have to work more for less,

given new stringent federal regulations

geared to decrease by-catch in shrimp nets,

the dwindling shrimp population which

he attributes to pollution and a voluntarily

more sustainable approach to the business,

that it’s all worth it.

“O ur customers appreciate it,” Potter

says.

Standing on the deck of the Cape Point

docked in front of the quaint yellow seafood

shack, with its towering outriggers

overhead, lines neatly taught, A pril Potter

lunges slightly toward their exploring toddler,

A .J. She says she misses her twelvehour

stints on the Cape Point.

“I never had trouble sleeping when I got

off the boat. W alking, maybe, but never

sleeping!”

She goes on to to say that she attributes

their methods — pulling the nets every 45

minutes instead of the standard three hours,

constantly adjusting the nets to keep them

six to eight inches off the bottom — to the

quality product they unload at the end of

the day.

“O ur customers accuse us of dipping our

shrimp in syrup,” she says.

Jonathon Broome, recreational shrimper

out of C arolina Beach, formerly a federal

government employee can relate. Shrimp

don’t have to smell shrimpy, he says.

“C ustomers have asked me why my

shrimp don’t smell like shrimp” he says,

chuckling. “A lot of people don’t know the

truth about the shrimp market.” H e refers

to the freshness of the shrimp.

Shrimp can sit on boats, in markets and

on trucks for weeks at a time, treated with

Royce Potter and his wife, April, run Potter’s Seafood in Southport with their

15-month-old son, A.J., in tow.