35

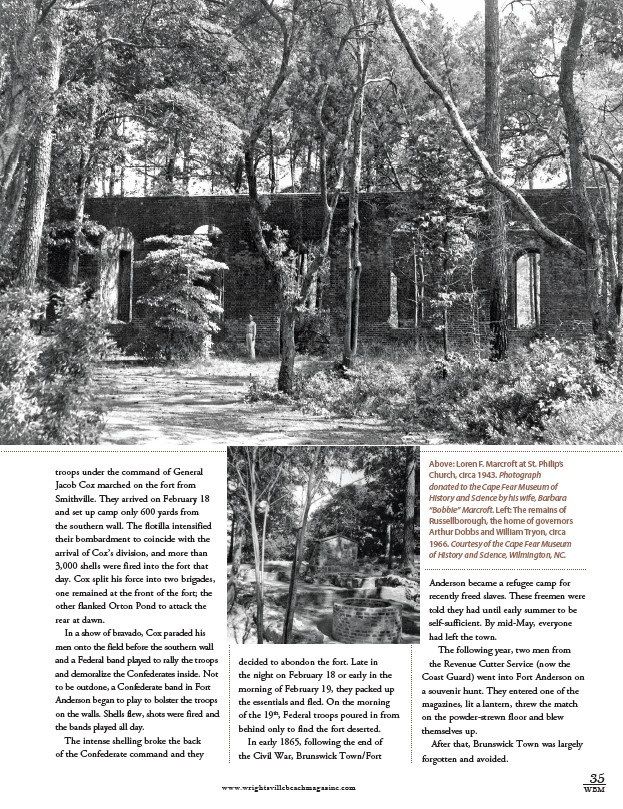

Above: Loren F. Marcroft at St. Philip’s

Church, circa 1943. Photograph

donated to the Cape Fear Museum of

History and Science by his wife, Barbara

“Bobbie” Marcroft. Left: The remains of

Russellborough, the home of governors

Arthur Dobbs and William Tryon, circa

1966. Courtesy of the Cape Fear Museum

of History and Science, Wilmington, NC.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM

troops under the command of General

Jacob Cox marched on the fort from

Smithville. They arrived on February 18

and set up camp only 600 yards from

the southern wall. The flotilla intensified

their bombardment to coincide with the

arrival of Cox’s division, and more than

3,000 shells were fired into the fort that

day. Cox split his force into two brigades,

one remained at the front of the fort; the

other flanked Orton Pond to attack the

rear at dawn.

In a show of bravado, Cox paraded his

men onto the field before the southern wall

and a Federal band played to rally the troops

and demoralize the Confederates inside. Not

to be outdone, a Confederate band in Fort

Anderson began to play to bolster the troops

on the walls. Shells flew, shots were fired and

the bands played all day.

The intense shelling broke the back

of the Confederate command and they

decided to abondon the fort. Late in

the night on February 18 or early in the

morning of February 19, they packed up

the essentials and fled. On the morning

of the 19th, Federal troops poured in from

behind only to find the fort deserted.

In early 1865, following the end of

the Civil War, Brunswick Town/Fort

Anderson became a refugee camp for

recently freed slaves. These freemen were

told they had until early summer to be

self-sufficient. By mid-May, everyone

had left the town.

The following year, two men from

the Revenue Cutter Service (now the

Coast Guard) went into Fort Anderson on

a souvenir hunt. They entered one of the

magazines, lit a lantern, threw the match

on the powder-strewn floor and blew

themselves up.

After that, Brunswick Town was largely

forgotten and avoided.