67

that with Roger, I was telling the guys, this place is a natural for a

preserve.”

It didn’t come without some controversy. Naysayers argue that

encouraging amateurs to dive wrecks could encourage removal of

historic artifacts.

“At the time when underwater archaeology was a nascent disci-pline,

the theory was if you’re not an underwater archaeologist you

don’t have any business being out here on wrecks,” Morris says.

“Well, I was diving on these wrecks before I could spell archaeol-ogy.

I’m a firm believer in don’t tell them what they can’t do, get

them to understand why they shouldn’t do it and then they will

work with you. If you go to Mount Vernon, do you feel an over-whelming

need to chisel a brick out of the privy and take it home?

No, you don’t, because you understand you have a shared respon-sibility

to a national treasure. We’re pushing for that here. Go look

at it. Just do it with respect. The Aussies don’t care if you go down

and dive the Great Barrier Reef, but they are going to get their

panties in a severe wad if you go down and take a big chunk off.

And it’ll grow back. But this won’t.”

The key is education, to ensure shipwrecks like the Condor are

viewed as national treasures like Mount Vernon.

“They are non-renewable resources,” Stratton says. “Once they

go, they’re gone. One of the things we’re starting to push very

much lately is teaching a sense of stewardship into the diving com-munity

and public. Take only pictures, leave only bubbles. This

is their shipwreck. It’s not just ours that we dive. This is North

Carolina’s. It’s their cultural maritime history.”

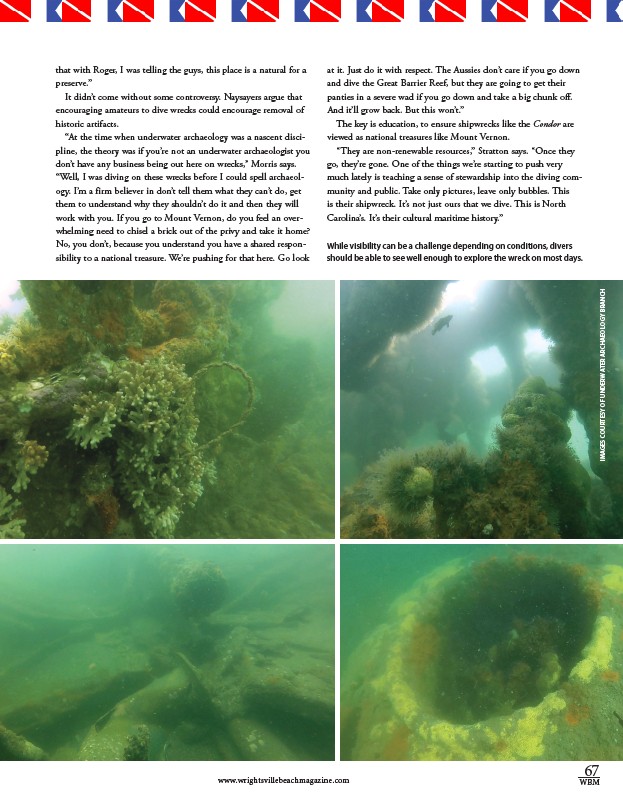

While visibility can be a challenge depending on conditions, divers

should be able to see well enough to explore the wreck on most days.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM

IMAGES COURTESY OF UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY BRANCH