A

At the time, Solano was running someone else’s

Viking, a premier sport fisherman. Comparing the BHM

to a Viking is like observing an ox beside a bull. The

Viking fiercely slices through the water. The Orion is the

ox: slow, strong and focused. It only travels at eight knots,

and when Solano takes it out he lives at sea on board for

two to five days.

Solano is an ox type of guy. He’s in his 30s and just mar-ried,

yet he is salty enough to be a fisherman from a much

earlier time. He and Orion are one.

The New Jersey native has been fishing most of his life,

and been involved in many aspects of the industry. Solano

received a degree in natural resource management and

fishery science from Rutgers School of Environmental and

Biological Sciences. He worked in the research field and

charter fished through college.

It was in New Jersey, where the water is cold and the

seasons short, that he first started fishing under the water,

beginning recreational diving and spearfishing by swim-ming

offshore to the Shrewsbury Rocks. This is where his

obsession with diving was born. He has the map tattooed

on his arm.

“The more I did it and improved at it, I realized I could

make a living doing it,” Solano says.

He bought Orion, had it shipped to North Carolina,

and began to transform it into an efficient commercial

spearfishing vessel. When he moved to Wilmington, he

bought a state permit that allowed him to sell fish like

African pompano, cobia and sheepshead.

“I didn’t know much about spearfishing here at first,” he

says. “I was more into free diving then. Even to this day, I

like it better, but commercially I realized to make a living

doing it, you have to strap on a tank.”

He also realized he’d have to get a federal permit called

a South Atlantic Snapper-Grouper Unlimited to turn a

profit. These fish are a spearfisherman’s bread and butter,

but a finite number of the permits exist, and they are being

retired at a quick rate. A fisherman must buy a permit that

already exists, and it can run up to $70,000.

This job is a lifestyle eliciting intense dedication. It

calls for diligence and demands a never-ending eager-ness

to learn. Fishermen work even when they’re not at

sea. Solano’s “off days” consist of maintaining the boat or

tackle, watching the weather and tides, and studying chlo-rophyll

levels to determine the visibility of the water. Any

spare time is spent telling fish tales and bending the ear of

other fishermen in an attempt to decipher what’s biting

that day.

“I’ll almost always have the boat ready to go,” Solano says.

The Orion leaves at night because the fishing ground

might be 75 miles away, which with her speed, could mean

a seven-hour boat ride. Solano usually brings one other

diver with him. One takes a shift at the wheel while the

other sleeps. By morning light, they will be anchored up

and diving.

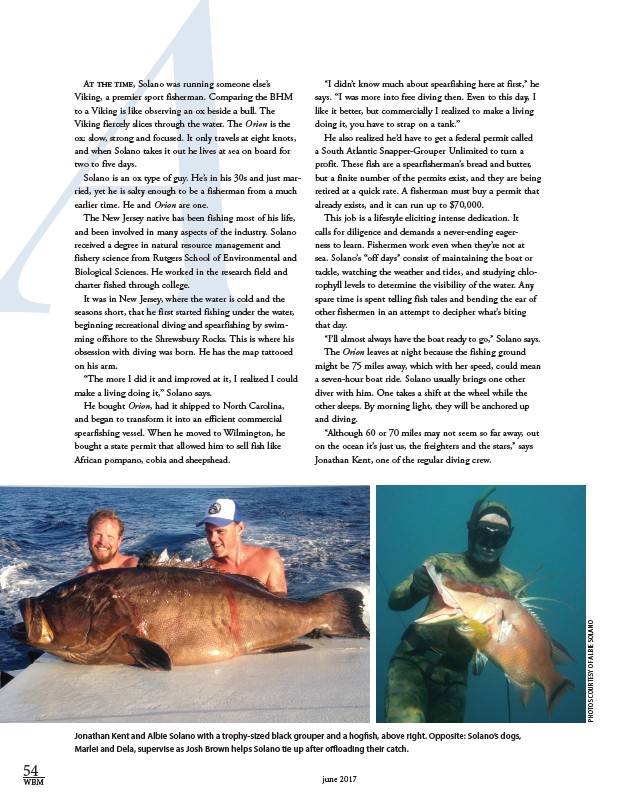

“Although 60 or 70 miles may not seem so far away, out

on the ocean it’s just us, the freighters and the stars,” says

Jonathan Kent, one of the regular diving crew.

Jonathan Kent and Albie Solano with a trophy-sized black grouper and a hogfish, above right. Opposite: Solano’s dogs,

Marlei and Dela, supervise as Josh Brown helps Solano tie up after offloading their catch.

54

WBM june 2017

PHOTOS COURTESY OF ALBIE SOLANO

A