OOne dives while the other stays on board and follows the

bubbles surfacing from the man below. It’s important for the

boat to be near when the diver comes up with a heavy stringer

of fish, often with a couple of sharks tailing him. The men say

it’s easier than it seems to lose a person in the water, especially

in strong currents and choppy seas.

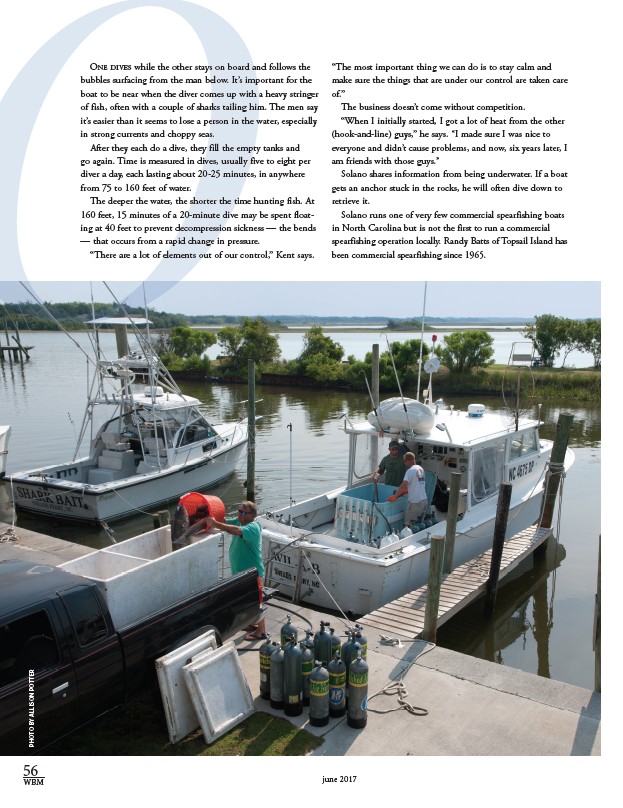

After they each do a dive, they fill the empty tanks and

go again. Time is measured in dives, usually five to eight per

diver a day, each lasting about 20-25 minutes, in anywhere

from 75 to 160 feet of water.

The deeper the water, the shorter the time hunting fish. At

160 feet, 15 minutes of a 20-minute dive may be spent float-ing

at 40 feet to prevent decompression sickness — the bends

— that occurs from a rapid change in pressure.

“There are a lot of elements out of our control,” Kent says.

“The most important thing we can do is to stay calm and

make sure the things that are under our control are taken care

of.”

The business doesn’t come without competition.

“When I initially started, I got a lot of heat from the other

(hook-and-line) guys,” he says. “I made sure I was nice to

everyone and didn’t cause problems, and now, six years later, I

am friends with those guys.”

Solano shares information from being underwater. If a boat

gets an anchor stuck in the rocks, he will often dive down to

retrieve it.

Solano runs one of very few commercial spearfishing boats

in North Carolina but is not the first to run a commercial

spearfishing operation locally. Randy Batts of Topsail Island has

been commercial spearfishing since 1965.

56

WBM june 2017 PHOTO BY ALLISON POTTER