Another tale of triumph for

conservationists is that of the

great egret. The bird’s image is

embroidered on the breast of Golder’s

shirt and hat, the symbol of the National

Audubon Society.

“That’s where the organization

started,” he says.

“Those wispy plumes,” Golder says

as he points to the striking white longlegged

shore birds, “were almost the end

of the great egret.”

Hunted for their plumage, which was

used for garnishing hats worn by women

around the turn of the 20th century, the

great egret’s story is much the same as

the brown pelican’s. It was only through

measures taken during the Audubon

Society’s beginnings in the 1880s and the

protesting of the mass slaughter of the

elegant birds that the species was saved.

Some of Audubon’s earliest conservation

efforts were concentrated close by.

“After the turn of the century,” Golder

says, “there was only one colony that was

known of in the early 1900s and that was

at Orton Plantation.”

The colony was guarded by one of the

state’s first hired game wardens.

Today, there are no such threatened

inhabitants of the Bird

Islands but these aviaries are

still guarded as if they were. The birds

depend on these sanctuaries — a place

where food is readily available and most

predators are too far away to swim.

When a predator is spotted, birds take

flight, blanketing the sky like a quilt of

winged creatures.

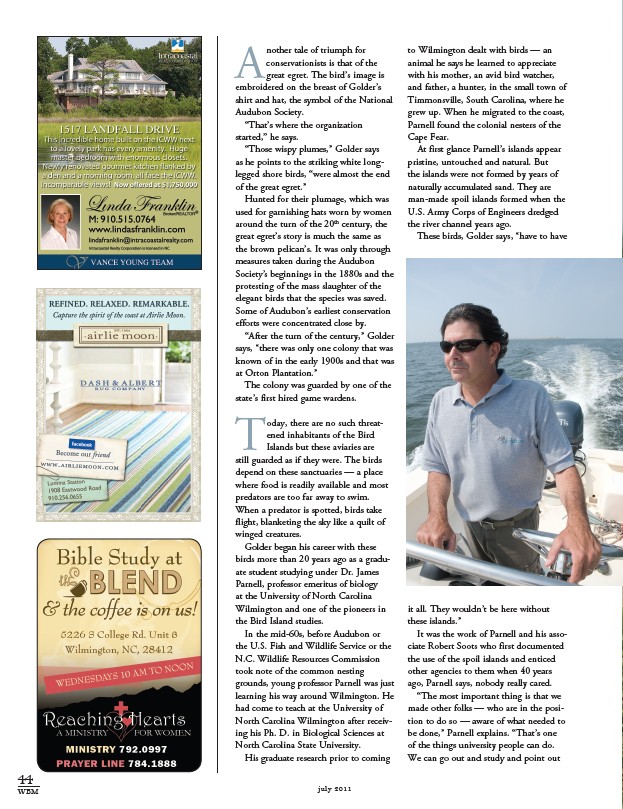

Golder began his career with these

birds more than 20 years ago as a graduate

student studying under Dr. James

Parnell, professor emeritus of biology

at the University of North Carolina

Wilmington and one of the pioneers in

the Bird Island studies.

In the mid-60s, before Audubon or

the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the

N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission

took note of the common nesting

grounds, young professor Parnell was just

learning his way around Wilmington. He

had come to teach at the University of

North Carolina Wilmington after receiving

his Ph. D. in Biological Sciences at

North Carolina State University.

His graduate research prior to coming

44

WBM july 2011

to Wilmington dealt with birds — an

animal he says he learned to appreciate

with his mother, an avid bird watcher,

and father, a hunter, in the small town of

Timmonsville, South Carolina, where he

grew up. When he migrated to the coast,

Parnell found the colonial nesters of the

Cape Fear.

At first glance Parnell’s islands appear

pristine, untouched and natural. But

the islands were not formed by years of

naturally accumulated sand. They are

man-made spoil islands formed when the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged

the river channel years ago.

These birds, Golder says, “have to have

it all. They wouldn’t be here without

these islands.”

It was the work of Parnell and his associate

Robert Soots who first documented

the use of the spoil islands and enticed

other agencies to them when 40 years

ago, Parnell says, nobody really cared.

“The most important thing is that we

made other folks — who are in the position

to do so — aware of what needed to

be done,” Parnell explains. “That’s one

of the things university people can do.

We can go out and study and point out