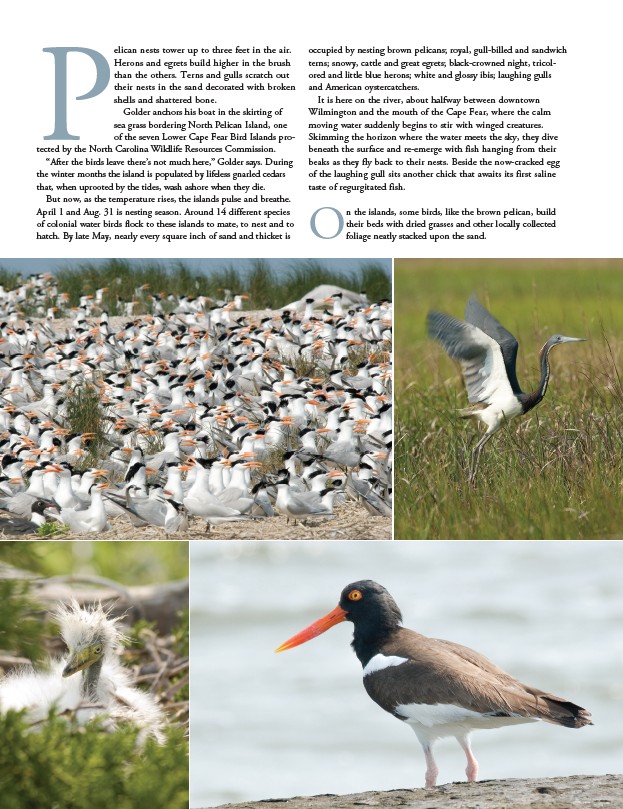

Pelican nests tower up to three feet in the air.

Herons and egrets build higher in the brush

than the others. Terns and gulls scratch out

their nests in the sand decorated with broken

shells and shattered bone.

Golder anchors his boat in the skirting of

sea grass bordering North Pelican Island, one

of the seven Lower Cape Fear Bird Islands protected

by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

“After the birds leave there’s not much here,” Golder says. During

the winter months the island is populated by lifeless gnarled cedars

that, when uprooted by the tides, wash ashore when they die.

But now, as the temperature rises, the islands pulse and breathe.

April 1 and Aug. 31 is nesting season. Around 14 different species

of colonial water birds flock to these islands to mate, to nest and to

hatch. By late May, nearly every square inch of sand and thicket is

occupied by nesting brown pelicans; royal, gull-billed and sandwich

terns; snowy, cattle and great egrets; black-crowned night, tricolored

and little blue herons; white and glossy ibis; laughing gulls

and American oystercatchers.

It is here on the river, about halfway between downtown

Wilmington and the mouth of the Cape Fear, where the calm

moving water suddenly begins to stir with winged creatures.

Skimming the horizon where the water meets the sky, they dive

beneath the surface and re-emerge with fish hanging from their

beaks as they fly back to their nests. Beside the now-cracked egg

of the laughing gull sits another chick that awaits its first saline

taste of regurgitated fish.

On the islands, some birds, like the brown pelican, build

their beds with dried grasses and other locally collected

foliage neatly stacked upon the sand.

42

WBM july 2011