savor

changing P E RC E P T I O N

Before the Civil War, North Carolina ranked as the leading wine

producer in the United States. Muscadine wine was so popular by

the early 20th century that North Carolina enjoyed a reputation

rivalling Napa Valley.

In 1919, Prohibition changed everything — although urban leg-end

has doctors prescribing scuppernong “tonic.” Upon its repeal,

drier European wines flooded the increasingly sophisticated market,

leaving muscadines to moonshiners.

Today, it’s esti-mated

there are

about 3,200 acres of

muscadines planted

throughout the

Southeast, mainly

in Georgia, North

Carolina, South

Carolina, Mississippi

and Florida. Typically,

the wines are made in

a sweet style, making

oenophiles scoff at the

thought of sipping a

muscadine wine.

Duplin Winery,

North Carolina’s

oldest vineyard,

has started to see a

shift in muscadine

wine consumption.

Co-owner Jonathan Fussell says there has been an increase in their

wines on restaurant menus, partly due to a revived interest in food

and drink indigenous to a region.

In the true tradition of a Southern cook’s waste not, want not ethos,

thrifty, flavor-conscious cooks figured out a long time ago how to

make use of every part of the fruit. They squeezed the pulp out of their

skins into a bowl, catching the juice and saving the thick skins (hulls).

After discarding the big, round seeds, the pulp and hulls were cooked

together and turned into jelly, fermented into wine, or simmered with

sugar, a bit of flour, and butter to make a thick, juicy lattice-topped

hull pie.

Between the steps involved in preparation, the shortness of

their season and the challenges of finding these heirloom gems,

the pie has faded from its former glory of the first half of the 20th

century, when it was a staple in Southern kitchens. Scuppernong

hull pie recipes are Southern relics of a forgotten time these days,

passed down like treasures.

Nancie McDermott, author of “Southern Pies,” grew up spitting

out hulls in her grandparents’ arbor.

“I cherish scuppernongs. I like the frugality and respect for ingre-dients,”

she says. But she admits making a pie is quite a production.

When they’re cooked, scuppernongs have a sweet and tart flavor

bursting with tones of honeysuckle, wildflower and orange blos-som.

American chefs are rediscovering their ancient charms and

creating a new iden-tity

for them with

modern sensibilities,

in both savory and

sweet dishes.

“The skin holds

its shape but loses its

chewy brawn, and

the flesh becomes

the jammy essence

of muscadine,” says

chef Vivian Howard,

author of “Deep Run

Roots.” “If the seeds

weren’t such a pain to

extract, I’d probably

put roasted musca-dines

on everything

from ice cream to

steak.”

Chef Hugh

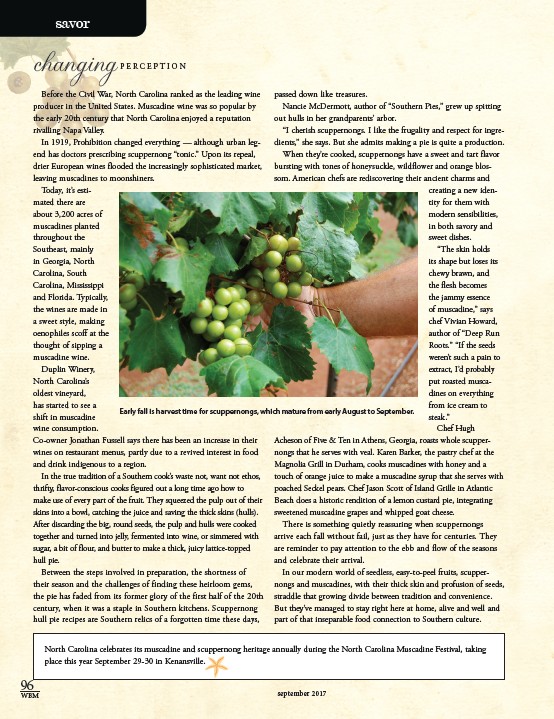

Early fall is harvest time for scuppernongs, which mature from early August to September.

Acheson of Five & Ten in Athens, Georgia, roasts whole scupper-nongs

that he serves with veal. Karen Barker, the pastry chef at the

Magnolia Grill in Durham, cooks muscadines with honey and a

touch of orange juice to make a muscadine syrup that she serves with

poached Seckel pears. Chef Jason Scott of Island Grille in Atlantic

Beach does a historic rendition of a lemon custard pie, integrating

sweetened muscadine grapes and whipped goat cheese.

There is something quietly reassuring when scuppernongs

arrive each fall without fail, just as they have for centuries. They

are reminder to pay attention to the ebb and flow of the seasons

and celebrate their arrival.

In our modern world of seedless, easy-to-peel fruits, scupper-nongs

and muscadines, with their thick skin and profusion of seeds,

straddle that growing divide between tradition and convenience.

But they’ve managed to stay right here at home, alive and well and

part of that inseparable food connection to Southern culture.

North Carolina celebrates its muscadine and scuppernong heritage annually during the North Carolina Muscadine Festival, taking

place this year September 29-30 in Kenansville.

september 2017 96

WBM