Bane’s handler then was S. Dixon, who has since left the unit.

Master Deputy G. Pedersen, who joined the sheriff ’s department

in 2009 after 22 years with the New York City PD, has been in

charge of Bane since May.

“He’s a celebrity,” Pedersen says. “My joke is that I chauffer a

celebrity around.”

A celebrity to the public, maybe, but the deputies affectionately

call him the department goofball. Bane belies the stereotype of

a police dog. His job is to find missing children and dementia

patients who wander off. He doesn’t track suspects, so he is not

trained to be aggressive.

“When he is tracking and he finds you, he’s going to lick you,

he’s going to jump in your lap,” Stegall says. “He’s happy. And he

knows food is coming. He has a food reward. The dog loves those

little dollar packets of tuna.”

Bane might never track and apprehend a suspect, but he does

use the same tool as his more aggressive kennel mates.

“Everything they do is because of their nose,” Stegall says.

“Kids always ask about how strong their noses are. This is my

analogy. Someone’s cooking chili, you walk in their home and

smell chili. A dog can walk in and tell you, if they could talk, the

meat, the spices, the beans, the sauce. They could break down

each individual ingredient. That’s how strong their noses are.”

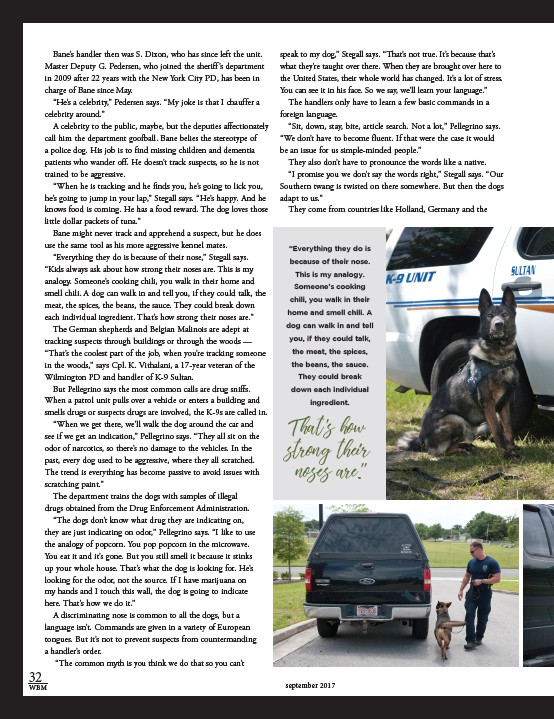

The German shepherds and Belgian Malinois are adept at

tracking suspects through buildings or through the woods —

“That’s the coolest part of the job, when you’re tracking someone

in the woods,” says Cpl. K. Vithalani, a 17-year veteran of the

Wilmington PD and handler of K-9 Sultan.

But Pellegrino says the most common calls are drug sniffs.

When a patrol unit pulls over a vehicle or enters a building and

smells drugs or suspects drugs are involved, the K-9s are called in.

“When we get there, we’ll walk the dog around the car and

see if we get an indication,” Pellegrino says. “They all sit on the

odor of narcotics, so there’s no damage to the vehicles. In the

past, every dog used to be aggressive, where they all scratched.

The trend is everything has become passive to avoid issues with

scratching paint.”

The department trains the dogs with samples of illegal

drugs obtained from the Drug Enforcement Administration.

“The dogs don’t know what drug they are indicating on,

they are just indicating on odor,” Pellegrino says. “I like to use

the analogy of popcorn. You pop popcorn in the microwave.

You eat it and it’s gone. But you still smell it because it stinks

up your whole house. That’s what the dog is looking for. He’s

looking for the odor, not the source. If I have marijuana on

my hands and I touch this wall, the dog is going to indicate

here. That’s how we do it.”

A discriminating nose is common to all the dogs, but a

language isn’t. Commands are given in a variety of European

tongues. But it’s not to prevent suspects from countermanding

a handler’s order.

“The common myth is you think we do that so you can’t

speak to my dog,” Stegall says. “That’s not true. It’s because that’s

what they’re taught over there. When they are brought over here to

the United States, their whole world has changed. It’s a lot of stress.

You can see it in his face. So we say, we’ll learn your language.”

The handlers only have to learn a few basic commands in a

foreign language.

“Sit, down, stay, bite, article search. Not a lot,” Pellegrino says.

“We don’t have to become fluent. If that were the case it would

be an issue for us simple-minded people.”

They also don’t have to pronounce the words like a native.

“I promise you we don’t say the words right,” Stegall says. “Our

Southern twang is twisted on there somewhere. But then the dogs

adapt to us.”

They come from countries like Holland, Germany and the

“Everything they do is

because of their nose.

This is my analogy.

Someone’s cooking

chili, you walk in their

home and smell chili. A

dog can walk in and tell

you, if they could talk,

the meat, the spices,

the beans, the sauce.

They could break

down each individual

ingredient.

That's how

strong their

noses are."

32

WBM september 2017