call away. Customers can call or e-mail LINC, and pick up their

order within a few days.

And there is always something available for individuals

who just show up at the farm, Roberts says, “even if it is

nothing but a good story.”

The facility can accommodate up to 40 residents at a time,

and Roberts says about 100 men and women come through

every year. The average length of stay is six months.

“The farm has taken the edge off our sometimes-unattract-ive

mission,” Roberts says. “That has been our struggle, to not

be viewed as an organization that helps so-called criminals.

Since we’ve been farming, people don’t necessarily say that as

much. They look at us more like farmers. It’s also helped our

residents eat healthier, because this is a food desert. And it

allows us to bring in program income.”

For many of the residents, the LINC Urban Farm represents

a second chance — a way to begin anew. John Blackwelder, a

current resident, says the farm has been successful in its goal

of helping former prisoners.

“We have internet, cable, food,” he says. “I mean, it’s just a

comfortable place to stay. And when you get out of prison,

it’s somewhere to go where you don’t have to immediately

try to jump back into all of the responsibilities that you

would normally have. So, it kind of gives you a chance to

work on the things that you need to get done.”

LINC has helped reintegrate 1,200 people into the commu-nity

since 2002. Roberts says 92 percent have remained out

of prison. The farm is a big part of that success.

“The farm puts you in a position to do for yourself and not

have to focus on somebody else doing it for you,” Roberts

says. “That’s another farm model. You’ve got to do for yourself.

You’ve got to get out there and get it.”

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com

21

WBM

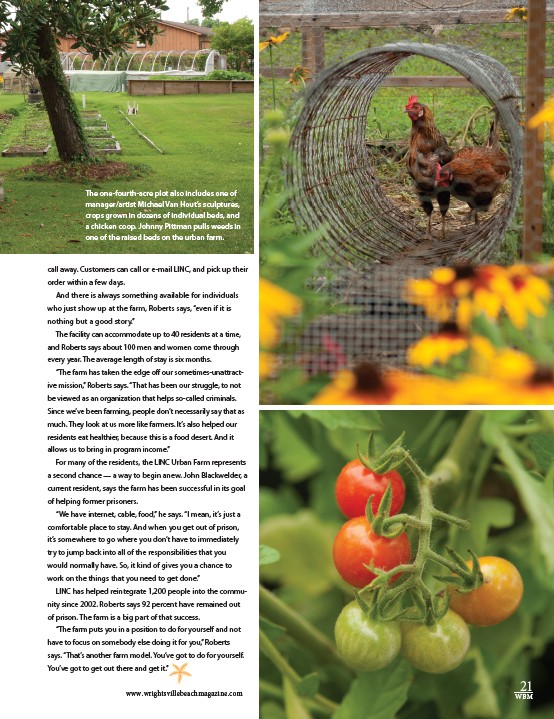

The one-fourth-acre plot also includes one of

manager/artist Michael Van Hout’s sculptures,

crops grown in dozens of individual beds, and

a chicken coop. Johnny Pittman pulls weeds in

one of the raised beds on the urban farm.