“I often compare it to a flounder. It’s a nice,

“Not so

much grill-ing

white flaky fish. It lends itself well to a

because the

fillets are thin. But

sautéing, baking, broil-ing,

frying. It’s not oily like a

few preparations,”

Rhodes

says.

mackerel, or bony like other bottom-dwellers,

or anything like that. It’s a

delicious fish. We sell out of it all the

time we have it.”

So does Brent Williams, owner and

chef at Brent’s Bistro.

“Most people are curious to try it,”

he says. “Then they are blown away. It’s

an easy sell once people find out how

good it is. They’re an ugly fish, but they

are delicious.”

When lionfish is on the menu, every-one

benefits. Commercial fishermen

can take as many as they want without

the fear of overfishing. Seafood con-sumers

can enjoy a delicious meal that

benefits the local marine ecology.

“Just the fact that we’re seeing them

now locally and can get them is incred-ible,”

Williams says. “We’re catching

them right off our coast. If it’s on the

plate, it’s good for the environment. It’s

a win-win.”

For commercial spearfishermen,

lionfish tend to be seasonal. There are

no restrictions at any time of the year,

but it makes more economic sense

during the warm summer months to

hunt larger fish like grouper that fetch

a greater price while they are in season.

That leads to a lack of availability at

restaurants and fish houses.

“It’s so unpredictable when the divers

go out for them,” Surratt says. “I call

Motts every morning, and if they have

lionfish I’ll ask for it. It’s probably about

two, three times a month I can get it.”

Even when lionfish are available, they

aren’t always in high demand. For one

thing, there’s the exotic appearance.

Lionfish don’t look like anything else on

display at Motts.

88

WBM july 2017

“You get

a mixed bag,”

Simpson says.

“Some people think

they are weird looking, some

people think they are cool look-ing.

A lot of people are surprised we

have them.”

Then there’s the perception that

they might be poisonous. That’s what

McInnis thought the first time he was

offered a lionfish.

“A friend said, ‘I have a special treat,’”

he says. “I was like, ‘Whoa, dude, is my

mouth going to go numb?’”

Williams sometimes hears the same

thing at Brent’s Bistro.

“I’ve had some customers joke, ‘If

my lips turn blue call an ambulance,’’’

he says.

Proponents of eating lionfish point

out that they are perfectly safe to eat.

“The poison is located in the spines,”

Simpson says. “A couple of hours after

they die, it’s harmless. It’s still quite a

serious needle, but the toxin is harm-less.

And it’s not in the meat at all.”

For now, the bulk of the catch is

brought in by spearfishermen. An ecol-ogy

group in Pensacola, Florida — the

self-proclaimed lionfish capital of the

world because of the amount of them

teeming in the warm waters off the

Florida panhandle — is experimenting

with traps that could remove them in

bulk without harming other species.

As word gets out and they become

more popular as seafood, there could be

a greater effort to catch and to eat them.

“I tend to think as awareness grows,

folks will search for lionfish when

they go out,” Rhodes says. “We can’t

eat flounder all the time. There’s a

wave and passion now for sustainable

seafood. We have to look at our local

aquatic system and how we can ensure

there’s future fish out there for people

to enjoy.”

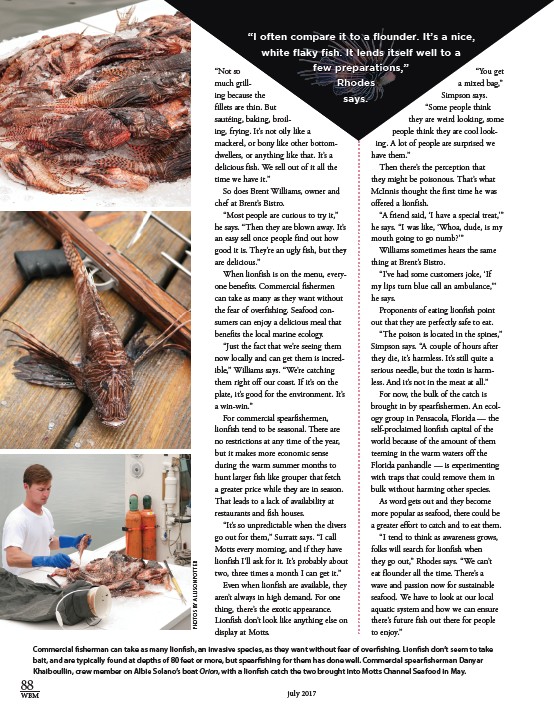

PHOTOS BY ALLISON POTTER

Commercial fisherman can take as many lionfish, an invasive species, as they want without fear of overfishing. Lionfish don’t seem to take

bait, and are typically found at depths of 80 feet or more, but spearfishing for them has done well. Commercial spearfisherman Danyar

Khaiboullin, crew member on Albie Solano’s boat Orion, with a lionfish catch the two brought into Motts Channel Seafood in May.