WHAT IS A BARRIER ISLAND?

T

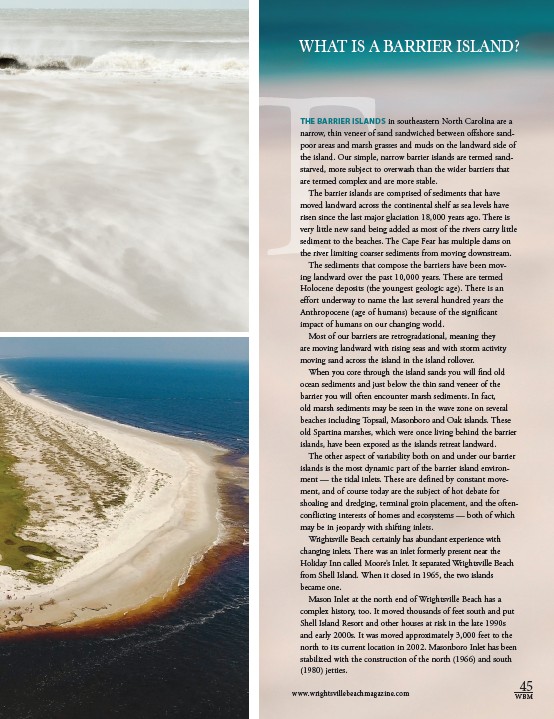

THE BARRIER ISLANDS in southeastern North Carolina are a

narrow, thin veneer of sand sandwiched between offshore sand-poor

areas and marsh grasses and muds on the landward side of

the island. Our simple, narrow barrier islands are termed sand-starved,

more subject to overwash than the wider barriers that

are termed complex and are more stable.

The barrier islands are comprised of sediments that have

moved landward across the continental shelf as sea levels have

risen since the last major glaciation 18,000 years ago. There is

very little new sand being added as most of the rivers carry little

sediment to the beaches. The Cape Fear has multiple dams on

the river limiting coarser sediments from moving downstream.

The sediments that compose the barriers have been mov-ing

landward over the past 10,000 years. These are termed

Holocene deposits (the youngest geologic age). There is an

effort underway to name the last several hundred years the

Anthropocene (age of humans) because of the significant

impact of humans on our changing world.

Most of our barriers are retrogradational, meaning they

are moving landward with rising seas and with storm activity

moving sand across the island in the island rollover.

When you core through the island sands you will find old

ocean sediments and just below the thin sand veneer of the

barrier you will often encounter marsh sediments. In fact,

old marsh sediments may be seen in the wave zone on several

beaches including Topsail, Masonboro and Oak islands. These

old Spartina marshes, which were once living behind the barrier

islands, have been exposed as the islands retreat landward.

The other aspect of variability both on and under our barrier

islands is the most dynamic part of the barrier island environ-ment

— the tidal inlets. These are defined by constant move-ment,

and of course today are the subject of hot debate for

shoaling and dredging, terminal groin placement, and the often-conflicting

interests of homes and ecosystems — both of which

may be in jeopardy with shifting inlets.

Wrightsville Beach certainly has abundant experience with

changing inlets. There was an inlet formerly present near the

Holiday Inn called Moore’s Inlet. It separated Wrightsville Beach

from Shell Island. When it closed in 1965, the two islands

became one.

Mason Inlet at the north end of Wrightsville Beach has a

complex history, too. It moved thousands of feet south and put

Shell Island Resort and other houses at risk in the late 1990s

and early 2000s. It was moved approximately 3,000 feet to the

north to its current location in 2002. Masonboro Inlet has been

stabilized with the construction of the north (1966) and south

(1980) jetties.

45

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM