BEACH RENOURISHMENT

In developed areas, periodic sand renourishment helps

protect structures and helps to keep the island “in place.”

Wrightsville Beach is quite stable with the numerous coastal

storm damage reduction projects, a total of 25, that have

been done and continue to be completed every four years.

The renourishment sand for Wrightsville Beach is usually

sourced from Masonboro Inlet. The longshore transport

that moves the sand from north to south also moves some

of that sand into Masonboro Inlet. Sands placed on beaches

must have similar composition and texture to the naturally

occurring sand, so the Masonboro Inlet sands are an excel-lent

source.

(For more about coastal storm damage reduction projects

in our region, see “State of the Sand” by Layton Bedsole in

WBM’s January 2017 edition.)

EROSION

On our beaches, erosion and moving sand are the norm.

The default erosion rate in North Carolina that is used to

guide development is 2 feet per year. Though Wrightsville

Beach erodes less than 2 feet per year because of the peri-odic

renourishment, this value is still used in calculations

of setbacks and planning. Higher erosion rates do occur.

The erosion rate at Kure Beach south of the seawall at Fort

Fisher is up to 9 feet per year; no renourishment occurs

at this location. Parts of Masonboro Island are eroding

at 8 feet per year. The Division of Coastal Management

determines and posts the erosion rates and setbacks for the

North Carolina coast.

LONGSHORE TRANSPORT

One of the obvious changes on the beach is related to

longshore transport, which moves sand along the beach —

the beach front is sometimes called a river of sand.

Imagine a conveyor moving thousands of cubic yards of

sand each year from north to south. The sand movement is

controlled by the wave action and the angle that the waves

impact the beach.

Along Wrightsville Beach, the sand dominantly moves

from north to south. However, it also may move north and

sometimes the waves arrive perpendicular to the beach and

the sand just moves up and back with the waves. This lat-ter

case is when rip currents are most likely; rip currents are

worst at low tide and with waves that arrive perpendicular

to the coastline.

You can experience longshore transport by looking at the

sand movement in the swash zone or you can feel the effect

by floating in the breaker zone. You will be moved down, or

up, the beach away from your towel, depending upon the

direction of longshore transport. Another way to observe

the effects of longshore transport is how the southerly mov-ing

sand piles up on the north side of Wrightsville Beach’s

south-end weir.

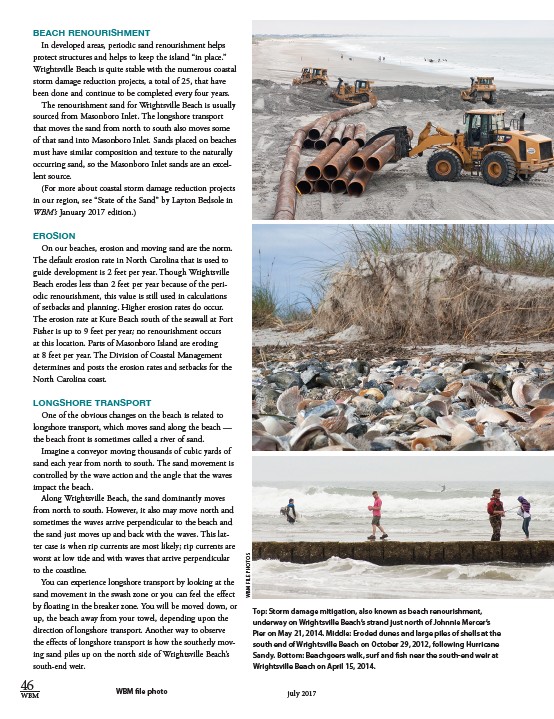

Top: Storm damage mitigation, also known as beach renourishment,

underway on Wrightsville Beach’s strand just north of Johnnie Mercer’s

Pier on May 21, 2014. Middle: Eroded dunes and large piles of shells at the

south end of Wrightsville Beach on October 29, 2012, following Hurricane

Sandy. Bottom: Beachgoers walk, surf and fish near the south-end weir at

Wrightsville Beach on April 15, 2014.

46

WBM file photo

WBM july 2017

WBM FILE PHOTOS