29

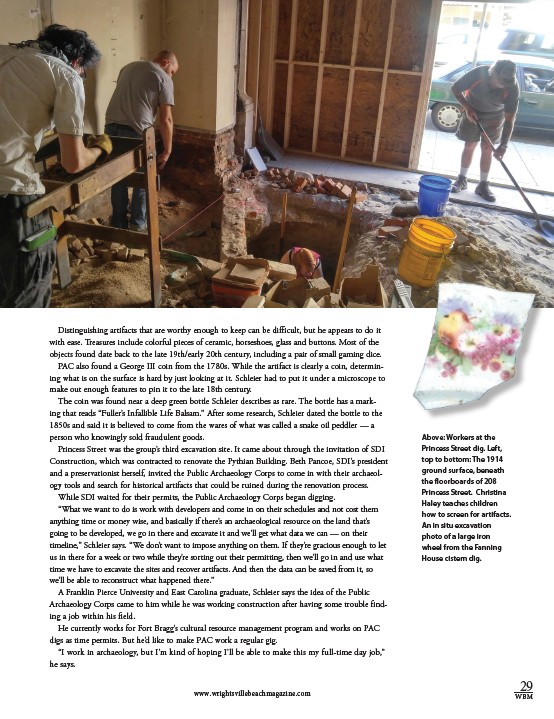

Above: Workers at the

Princess Street dig. Left,

top to bottom: The 1914

ground surface, beneath

the floorboards of 208

Princess Street. Christina

Haley teaches children

how to screen for artifacts.

An in situ excavation

photo of a large iron

wheel from the Fanning

House cistern dig.

Distinguishing artifacts that are worthy enough to keep can be difficult, but he appears to do it

with ease. Treasures include colorful pieces of ceramic, horseshoes, glass and buttons. Most of the

objects found date back to the late 19th/early 20th century, including a pair of small gaming dice.

PAC also found a George III coin from the 1780s. While the artifact is clearly a coin, determin-ing

what is on the surface is hard by just looking at it. Schleier had to put it under a microscope to

make out enough features to pin it to the late 18th century.

The coin was found near a deep green bottle Schleier describes as rare. The bottle has a mark-ing

that reads “Fuller’s Infallible Life Balsam.” After some research, Schleier dated the bottle to the

1850s and said it is believed to come from the wares of what was called a snake oil peddler — a

person who knowingly sold fraudulent goods.

Princess Street was the group’s third excavation site. It came about through the invitation of SDI

Construction, which was contracted to renovate the Pythian Building. Beth Pancoe, SDI’s president

and a preservationist herself, invited the Public Archaeology Corps to come in with their archaeol-ogy

tools and search for historical artifacts that could be ruined during the renovation process.

While SDI waited for their permits, the Public Archaeology Corps began digging.

“What we want to do is work with developers and come in on their schedules and not cost them

anything time or money wise, and basically if there’s an archaeological resource on the land that’s

going to be developed, we go in there and excavate it and we’ll get what data we can — on their

timeline,” Schleier says. “We don’t want to impose anything on them. If they’re gracious enough to let

us in there for a week or two while they’re sorting out their permitting, then we’ll go in and use what

time we have to excavate the sites and recover artifacts. And then the data can be saved from it, so

we’ll be able to reconstruct what happened there.”

A Franklin Pierce University and East Carolina graduate, Schleier says the idea of the Public

Archaeology Corps came to him while he was working construction after having some trouble find-ing

a job within his field.

He currently works for Fort Bragg’s cultural resource management program and works on PAC

digs as time permits. But he’d like to make PAC work a regular gig.

“I work in archaeology, but I’m kind of hoping I’ll be able to make this my full-time day job,”

he says.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM