HE PUBLIC ARCHAEOLOGY CORPS (PAC)

studies the unwritten historic record that lies

buried beneath the ground, specifically on

building and home sites that might be covered

forever by development.

“We formed to protect and address the

problem of archaeological site loss on privately owned land,”

Schleier says. “We have a long and varied history in this area

and not much work has been done.”

Schleier is happy to give an impromptu history lesson to

anyone who wanders by a site — and even put them to work.

It’s all part of his plan to make the public aware of the archae-ology

around them.

“The general public, they know that archaeology is

around but may not be aware that it happens here,” Schleier

says. “We’re trying a hearts-and-mind approach of public

education.”

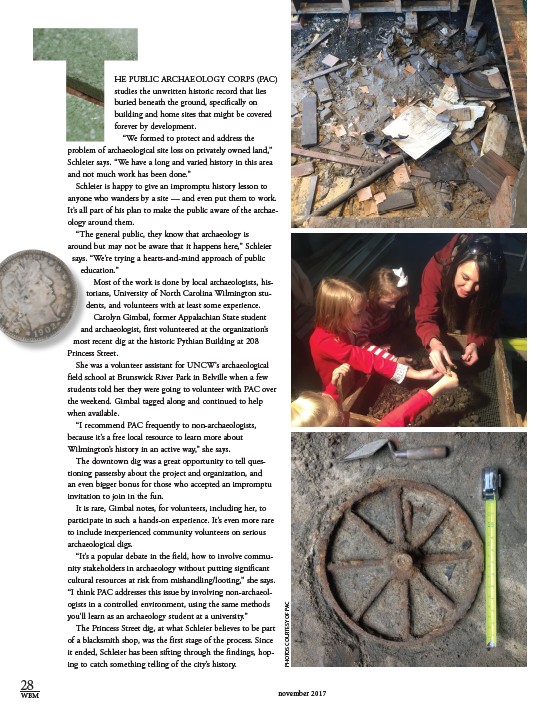

Most of the work is done by local archaeologists, his-torians,

University of North Carolina Wilmington stu-dents,

and volunteers with at least some experience.

Carolyn Gimbal, former Appalachian State student

and archaeologist, first volunteered at the organization’s

most recent dig at the historic Pythian Building at 208

Princess Street.

She was a volunteer assistant for UNCW’s archaeological

field school at Brunswick River Park in Belville when a few

students told her they were going to volunteer with PAC over

the weekend. Gimbal tagged along and continued to help

when available.

“I recommend PAC frequently to non-archaeologists,

because it’s a free local resource to learn more about

Wilmington’s history in an active way,” she says.

The downtown dig was a great opportunity to tell ques-tioning

passersby about the project and organization, and

an even bigger bonus for those who accepted an impromptu

invitation to join in the fun.

It is rare, Gimbal notes, for volunteers, including her, to

participate in such a hands-on experience. It’s even more rare

to include inexperienced community volunteers on serious

archaeological digs.

“It’s a popular debate in the field, how to involve commu-nity

stakeholders in archaeology without putting significant

cultural resources at risk from mishandling/looting,” she says.

“I think PAC addresses this issue by involving non-archaeol-ogists

in a controlled environment, using the same methods

you’ll learn as an archaeology student at a university.”

The Princess Street dig, at what Schleier believes to be part

of a blacksmith shop, was the first stage of the process. Since

it ended, Schleier has been sifting through the findings, hop-ing

to catch something telling of the city’s history.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF PAC

28

WBM november 2017