Fortunately,

efforts to identify

and protect

Carolina Bays

are underway by

state and federal

agencies in concert

with conservation

organizations.

And this good

work is not just

for the benefit of

birds, frogs and

wildflowers;

Carolina Bays

provide tangible

ecologic and

economic value,

with water as their

priceless currency.

53

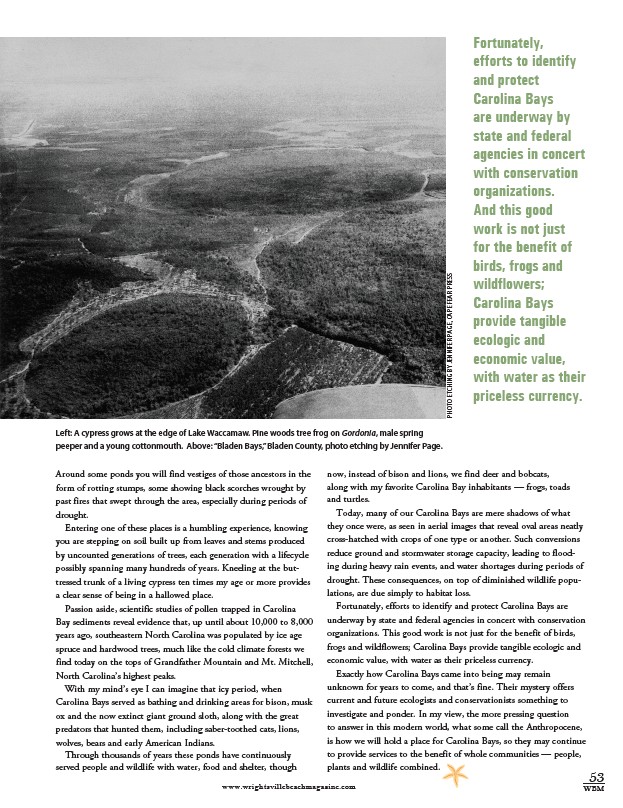

Left: A cypress grows at the edge of Lake Waccamaw. Pine woods tree frog on Gordonia, male spring

peeper and a young cottonmouth. Above: “Bladen Bays,” Bladen County, photo etching by Jennifer Page.

Around some ponds you will find vestiges of those ancestors in the

form of rotting stumps, some showing black scorches wrought by

past fires that swept through the area, especially during periods of

drought.

Entering one of these places is a humbling experience, knowing

you are stepping on soil built up from leaves and stems produced

by uncounted generations of trees, each generation with a lifecycle

possibly spanning many hundreds of years. Kneeling at the but-tressed

trunk of a living cypress ten times my age or more provides

a clear sense of being in a hallowed place.

Passion aside, scientific studies of pollen trapped in Carolina

Bay sediments reveal evidence that, up until about 10,000 to 8,000

years ago, southeastern North Carolina was populated by ice age

spruce and hardwood trees, much like the cold climate forests we

find today on the tops of Grandfather Mountain and Mt. Mitchell,

North Carolina’s highest peaks.

With my mind’s eye I can imagine that icy period, when

Carolina Bays served as bathing and drinking areas for bison, musk

ox and the now extinct giant ground sloth, along with the great

predators that hunted them, including saber-toothed cats, lions,

wolves, bears and early American Indians.

Through thousands of years these ponds have continuously

served people and wildlife with water, food and shelter, though

PHOTO ETCHING BY JENNIFER PAGE, CAPE FEAR PRESS

now, instead of bison and lions, we find deer and bobcats,

along with my favorite Carolina Bay inhabitants — frogs, toads

and turtles.

Today, many of our Carolina Bays are mere shadows of what

they once were, as seen in aerial images that reveal oval areas neatly

cross-hatched with crops of one type or another. Such conversions

reduce ground and stormwater storage capacity, leading to flood-ing

during heavy rain events, and water shortages during periods of

drought. These consequences, on top of diminished wildlife popu-lations,

are due simply to habitat loss.

Fortunately, efforts to identify and protect Carolina Bays are

underway by state and federal agencies in concert with conservation

organizations. This good work is not just for the benefit of birds,

frogs and wildflowers; Carolina Bays provide tangible ecologic and

economic value, with water as their priceless currency.

Exactly how Carolina Bays came into being may remain

unknown for years to come, and that’s fine. Their mystery offers

current and future ecologists and conservationists something to

investigate and ponder. In my view, the more pressing question

to answer in this modern world, what some call the Anthropocene,

is how we will hold a place for Carolina Bays, so they may continue

to provide services to the benefit of whole communities — people,

plants and wildlife combined.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM