Cannonball Jelly, 14 x 11 inches, mixed media on paper.

Martha the Pigeon

Martha the Passenger Pigeon is

interesting for its similarity to the cover

of The Goldfinch, Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer-

Prize winning novel. The attention to

detail draws the viewer in.

Martha was an endling, the last

known individual of a species. Her story

is an early example of conservation

efforts.

In the early 1900s, University of

Chicago professor Charles Whitman

recognized the population of once

prevalent passenger pigeons was

facing a steady decline. To establish a

stable population, Whitman attempted

to breed some of the survivors. He was

unsuccessful but his efforts raised awareness about extinction issues across

the nation. At one point, there was even a $1,000 reward for anyone who could

find a mate for Martha.

After her death at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914, Martha was preserved as a taxi-dermy

mount for display in the Smithsonian National Museum for Natural History.

She was exhibited at the museum for around 50 years, though she occasionally

appeared in various displays around the nation.

In the modern era, Martha has become a symbol of efforts to reintroduce

extinct species using synthetic biology.

The concept of rewilding the planet is something a lot of people get behind.

Returning a native poulation like wolves to the wild is something that many con-servations

cheer. Bringing other species back from extinction could be an effec-tive

means of bringing ecosystems back to balance. But concerns that rewilding

through genetic engineering or the reintroduction of native species could cause

a wide array of unforeseen problems are not uncommon.

The seemingly surface-level portrayal of Martha has much more depth

and complexity than initially meet the eye, making it a good introduction to

Perry’s work.

The Jellyfish

Any native of Southeast North Carolina will likely have a memory centered on

the sea mushrooms depicted in Perry’s “Cannonball,” as they are the perfect size

and shape to hurl at family and friends.

Similar to much of her work, the subject warrants further investigation. In

“Jellybunny,” Perry illustrates that the idea of inserting bioluminescent genes into

rabbits is being considered. Anyone under the age of 10 would never question

the wisdom of creating a glow-in-the-dark bunny, but that doesn’t mean it should

happen.

“I have always been intrigued by the line between attraction and repulsion, the

creepy versus the cute,” Perry says.

With “Medusoid,” Perry communicates that genetic engineering could someday

be used to splice jellyfish DNA into a human heart. Since the movement of jellyfish

in the water is similar to the ticking of a human heart, doing so could repair heart

issues.

“In many cases, it may seem like we are doing something good for society, but

what are the results?” she says. “A lot of my work is centered on the idea that mess-ing

with nature could have unintended consequences.”

54

WBM july 2020

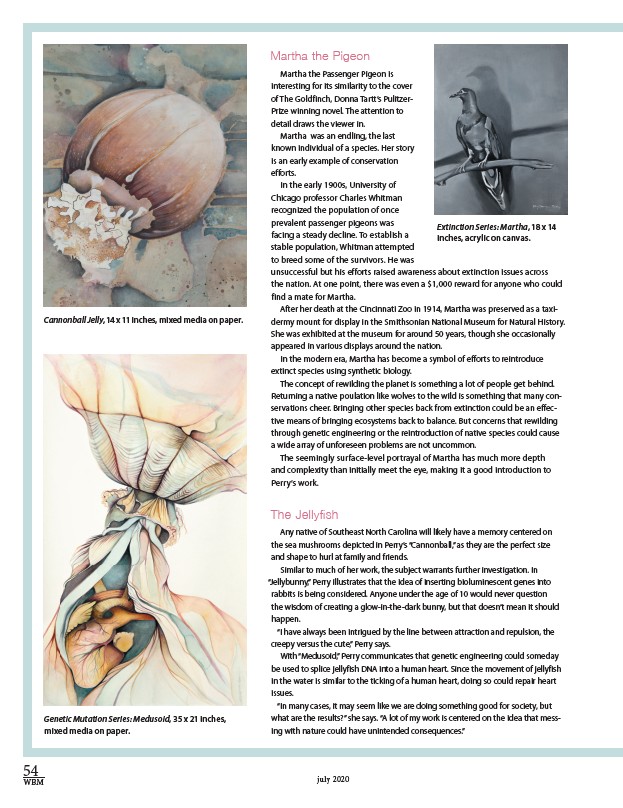

Extinction Series: Martha, 18 x 14

inches, acrylic on canvas.

Genetic Mutation Series: Medusoid, 35 x 21 inches,

mixed media on paper.