sinks into the ground and the root systems hold the soils and

absorb water,” Taylor says. “Always be aware of what pesticides and

fertilizers you use as those will end up in our water systems.”

As a sentinel species, oysters mirror the level of contaminant in

the water and surrounding sediments, reflecting the effect on the

environment. That we have witnessed such a sharp decline in the

oyster population in a short time period is a sign that local waters

are in big trouble, but efforts already in the works are proving

successful. The damage can be arrested and reversed.

The future of oysters is positive, and with continued diligence

by all involved, we might ultimately eliminate “Closed to Shellfish”

signs and enjoy all the benefits that a healthy local oyster popula-tion

41

THE University of North Carolina

Wilmington’s Center for Marine Science

Shellfish Hatchery at CREST Research

Park on Masonboro Sound operates a

12,000-square-foot facility dedicated to the propaga-tion

of marine bivalves, including oysters. The hatch-ery

has established outreach opportunities for the

community and offers high school internships along

with college undergraduate and graduate programs.

Under federal and state public trust doctrines,

individuals cannot own navigable waters or the lands

beneath them. However, the North Carolina General

Assembly recognizes the value of aquaculture, which

can be accomplished through various methods,

including seeding and growing oysters in racks. The

state has enacted laws allowing private citizens to

lease public waters for this purpose. Relevant legisla-tion

is being continually tweaked to maximize aqua-culture

harvesting incentives while sustaining healthy

growth and minimizing adverse effects on adjoining

riparian property owners.

North Carolina is coordinating with federal agen-cies,

including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to

increase the number of potential sites available state-wide

for shellfish leases. These agencies recognize the

value of incentivizing aquaculture, and that growing

the seafood industry will further promote environ-mental

stewardship, ultimately improving the health

of our waters.

Beyond growing more oysters, responsible steward-ship

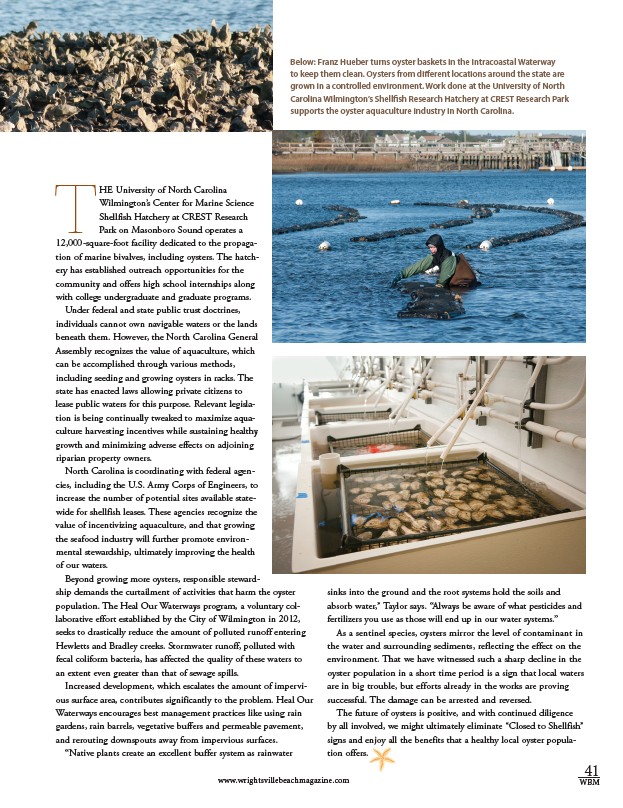

Below: Franz Hueber turns oyster baskets in the Intracoastal Waterway

to keep them clean. Oysters from different locations around the state are

grown in a controlled environment. Work done at the University of North

Carolina Wilmington’s Shellfish Research Hatchery at CREST Research Park

supports the oyster aquaculture industry in North Carolina.

demands the curtailment of activities that harm the oyster

population. The Heal Our Waterways program, a voluntary col-laborative

effort established by the City of Wilmington in 2012,

seeks to drastically reduce the amount of polluted runoff entering

Hewletts and Bradley creeks. Stormwater runoff, polluted with

fecal coliform bacteria, has affected the quality of these waters to

an extent even greater than that of sewage spills.

Increased development, which escalates the amount of impervi-ous

surface area, contributes significantly to the problem. Heal Our

Waterways encourages best management practices like using rain

gardens, rain barrels, vegetative buffers and permeable pavement,

and rerouting downspouts away from impervious surfaces.

“Native plants create an excellent buffer system as rainwater

offers.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM