AIRLIE’S RESEARCH REVEALS, SINCE THE EARLY 1900S,

North Carolina’s oyster population has declined roughly 90 percent due to disease,

habitat loss, pollution, declining water quality and harvest pressure.

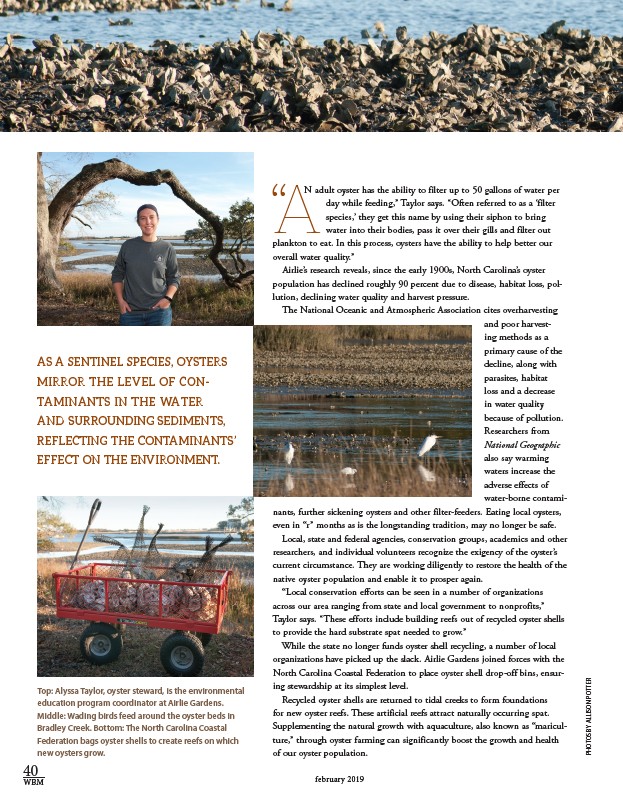

Top: Alyssa Taylor, oyster steward, is the environmental

education program coordinator at Airlie Gardens.

Middle: Wading birds feed around the oyster beds in

Bradley Creek. Bottom: The North Carolina Coastal

Federation bags oyster shells to create reefs on which

new oysters grow.

“A

40

WBM february 2019

PHOTOS BY ALLISON POTTER

N adult oyster has the ability to filter up to 50 gallons of water per

day while feeding,” Taylor says. “Often referred to as a ‘filter

species,’ they get this name by using their siphon to bring

water into their bodies, pass it over their gills and filter out

plankton to eat. In this process, oysters have the ability to help better our

overall water quality.”

Airlie’s research reveals, since the early 1900s, North Carolina’s oyster

population has declined roughly 90 percent due to disease, habitat loss, pol-lution,

declining water quality and harvest pressure.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association cites overharvesting

and poor harvest-ing

methods as a

primary cause of the

decline, along with

parasites, habitat

loss and a decrease

in water quality

because of pollution.

Researchers from

National Geographic

also say warming

waters increase the

adverse effects of

water-borne contami-nants,

further sickening oysters and other filter-feeders. Eating local oysters,

even in “r” months as is the longstanding tradition, may no longer be safe.

Local, state and federal agencies, conservation groups, academics and other

researchers, and individual volunteers recognize the exigency of the oyster’s

current circumstance. They are working diligently to restore the health of the

native oyster population and enable it to prosper again.

“Local conservation efforts can be seen in a number of organizations

across our area ranging from state and local government to nonprofits,”

Taylor says. “These efforts include building reefs out of recycled oyster shells

to provide the hard substrate spat needed to grow.”

While the state no longer funds oyster shell recycling, a number of local

organizations have picked up the slack. Airlie Gardens joined forces with the

North Carolina Coastal Federation to place oyster shell drop-off bins, ensur-ing

stewardship at its simplest level.

Recycled oyster shells are returned to tidal creeks to form foundations

for new oyster reefs. These artificial reefs attract naturally occurring spat.

Supplementing the natural growth with aquaculture, also known as “maricul-ture,”

through oyster farming can significantly boost the growth and health

of our oyster population.

AS A SENTINEL SPECIES, OYSTERS

MIRROR THE LEVEL OF CONTAMINANTS

IN THE WATER

AND SURROUNDING SEDIMENTS,

REFLECTING THE CONTAMINANTS’

EFFECT ON THE ENVIRONMENT.