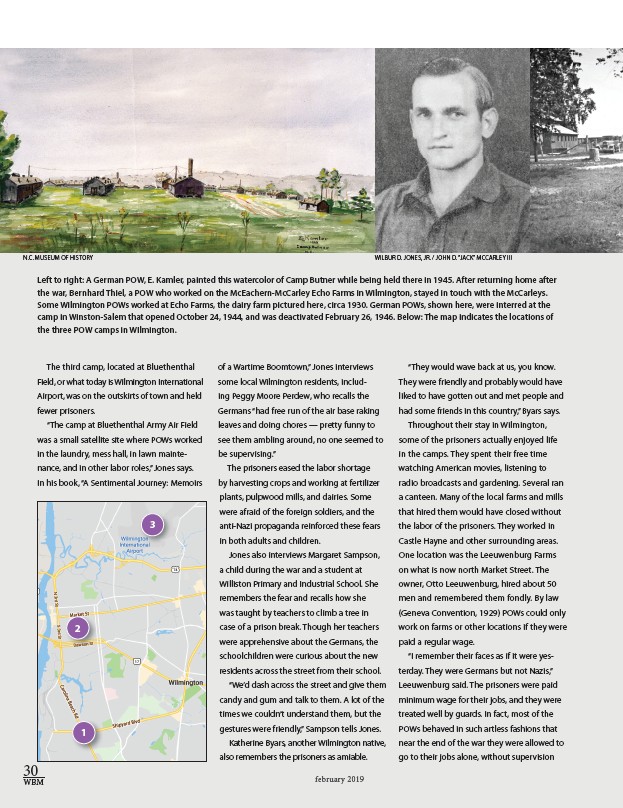

N.C. MUSEUM OF HISTORY WILBUR D. JONES, JR. / JOHN D. “JACK” MCCARLEY III

Left to right: A German POW, E. Kamler, painted this watercolor of Camp Butner while being held there in 1945. After returning home after

the war, Bernhard Thiel, a POW who worked on the McEachern-McCarley Echo Farms in Wilmington, stayed in touch with the McCarleys.

Some Wilmington POWs worked at Echo Farms, the dairy farm pictured here, circa 1930. German POWs, shown here, were interred at the

camp in Winston-Salem that opened October 24, 1944, and was deactivated February 26, 1946. Below: The map indicates the locations of

the three POW camps in WIlmington.

february 2019

The third camp, located at Bluethenthal

Field, or what today is Wilmington International

Airport, was on the outskirts of town and held

fewer prisoners.

“The camp at Bluethenthal Army Air Field

was a small satellite site where POWs worked

in the laundry, mess hall, in lawn mainte-nance,

and in other labor roles,” Jones says.

In his book, “A Sentimental Journey: Memoirs

of a Wartime Boomtown,” Jones interviews

some local Wilmington residents, includ-ing

Peggy Moore Perdew, who recalls the

Germans “had free run of the air base raking

leaves and doing chores — pretty funny to

see them ambling around, no one seemed to

be supervising.”

The prisoners eased the labor shortage

by harvesting crops and working at fertilizer

plants, pulpwood mills, and dairies. Some

were afraid of the foreign soldiers, and the

anti-Nazi propaganda reinforced these fears

in both adults and children.

Jones also interviews Margaret Sampson,

a child during the war and a student at

Williston Primary and Industrial School. She

remembers the fear and recalls how she

was taught by teachers to climb a tree in

case of a prison break. Though her teachers

were apprehensive about the Germans, the

schoolchildren were curious about the new

residents across the street from their school.

“We’d dash across the street and give them

candy and gum and talk to them. A lot of the

times we couldn’t understand them, but the

gestures were friendly,” Sampson tells Jones.

Katherine Byars, another Wilmington native,

also remembers the prisoners as amiable.

“They would wave back at us, you know.

They were friendly and probably would have

liked to have gotten out and met people and

had some friends in this country,” Byars says.

Throughout their stay in Wilmington,

some of the prisoners actually enjoyed life

in the camps. They spent their free time

watching American movies, listening to

radio broadcasts and gardening. Several ran

a canteen. Many of the local farms and mills

that hired them would have closed without

the labor of the prisoners. They worked in

Castle Hayne and other surrounding areas.

One location was the Leeuwenburg Farms

on what is now north Market Street. The

owner, Otto Leeuwenburg, hired about 50

men and remembered them fondly. By law

(Geneva Convention, 1929) POWs could only

work on farms or other locations if they were

paid a regular wage.

“I remember their faces as if it were yes-terday.

They were Germans but not Nazis,”

Leeuwenburg said. The prisoners were paid

minimum wage for their jobs, and they were

treated well by guards. In fact, most of the

POWs behaved in such artless fashions that

near the end of the war they were allowed to

go to their jobs alone, without supervision

1

2

3

30

WBM