BY COLLEEN THOMPSON POKÉ

raw fish traditions, adding soy sauce and

sesame oil.

It was in the 1970s that poké began to

rise in popularity. This coincided with

ahi tuna becoming more readily available

as it made its way out of Hawaiian home

kitchens and onto mainstream menus. In

its “Brief History of Poké in Hawaii,” the

Hawaiian Ocean Project states that legend-ary

Hawaiian chef and restaurateur Sam

Choy almost single-handedly brought poké

bowls to the masses. In 1991 he launched

his first poké contest, featuring recipes from

all over Hawaii. The contest encouraged

chefs to be creative and inventive with their

creations.

Soon after, the dish journeyed to the

mainland with Hawaii’s multicultural influ-ences

naturally mixing in. Poké bowls are

still very much part of the Hawaiian culture

and are often brought along to family gath-erings.

Today, Hawaiians eat limu-seasoned

poké, usually called Hawaiian or limu poké,

but ahi shoyu poké, which is a mix of tuna,

soy sauce, sesame oil, green onions and

chili, has become more popular.

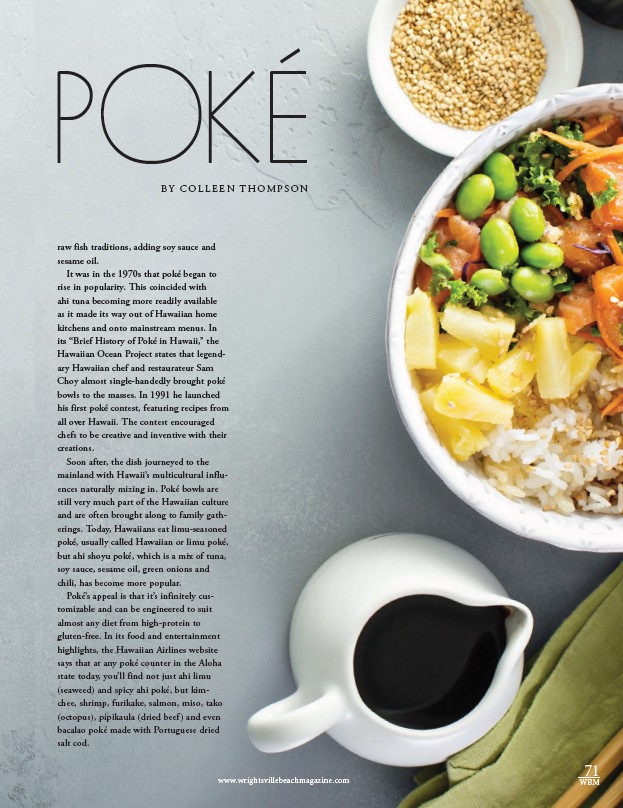

Poké’s appeal is that it’s infinitely cus-tomizable

and can be engineered to suit

almost any diet from high-protein to

gluten-free. In its food and entertainment

highlights, the Hawaiian Airlines website

says that at any poké counter in the Aloha

state today, you’ll find not just ahi limu

(seaweed) and spicy ahi poké, but kim-chee,

shrimp, furikake, salmon, miso, tako

(octopus), pipikaula (dried beef) and even

bacalao poké made with Portuguese dried

salt cod.

71

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM

o