gR O W I N G U P I N W R I G H T S V I L L E B E A C H ,

Walker Golder has been surrounded by birds and wildlife all of his life.

Early on, he developed a fascination with the seasonal comings and

goings of local wildlife — the summertime, when terns and skimmers

nested on remote beaches; the cooler months that brought ducks to the

marshes and shorebirds to the beaches. Bluefish, Spanish mackerel and

speckled trout each had their seasons of abundance, and each captured

his attention. This intrigue led to degrees in biology (BSc) and marine

biology (MSc) from UNCW. Fresh out of graduate school, he landed a

job with the National Audubon Society as the first manager of the newly

created North Carolina Coastal Islands Sanctuary program. Later on, he

launched the North Carolina Important Bird Areas Program and became

deputy state director when the state office was formed. Today he serves

as the director of the National Audubon Society’s Atlantic Flyway Coast

Strategy, where he works with organizations worldwide to advance con-servation

of coastal areas that are important to sustaining populations of

seabirds, shorebirds and marsh birds.

“I get excited when the terns and skimmers come back to nest, when

shorebirds from the Arctic arrive on our beaches, hearing the whistling

of ducks’ wings in the winter, and the moment a redfish takes a fly

crafted by my own hands,” Golder says. “Through it all I have stayed

connected to my roots and the rhythms of the coast. Whether pursu-ing

fishing, surfing, sailing, boating, or walking on the beach, any time

spent in the proximity of water refreshes me.”

Migration in the region varies depending on the species. For some

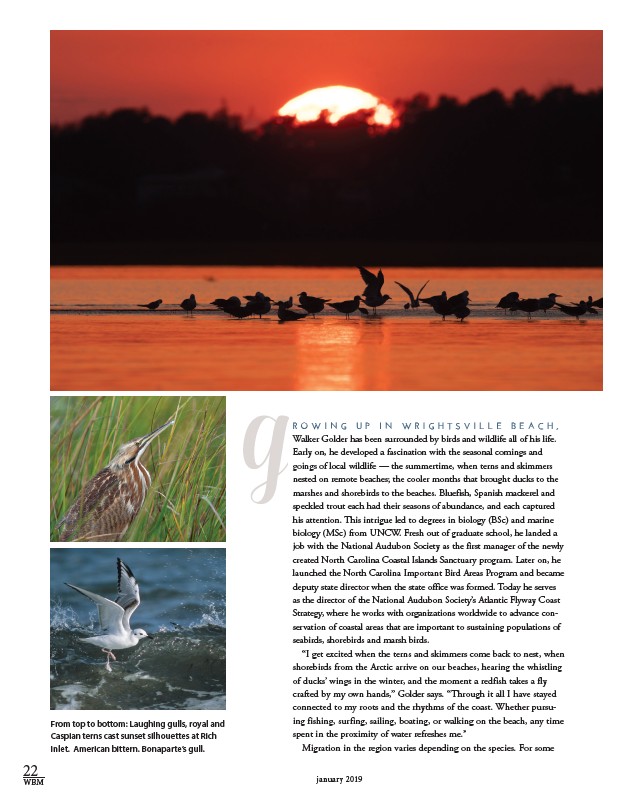

From top to bottom: Laughing gulls, royal and

Caspian terns cast sunset silhouettes at Rich

Inlet. American bittern. Bonaparte’s gull.

22

WBM january 2019