L T H O U G H M O S T P E O P L E

associate the beach with gulls, there are many

more bird species that are found in southeast-ern

North Carolina. Most species of shorebirds

— sandpipers, plovers, and their relatives — nest in the far

north, as far as the Arctic, and winter in the south, anywhere

from the mid-Atlantic coast of the U.S. to South America,”

Addison says. “They depend on coastal habitats, especially

inlets, for places to forage and rest on their long migrations.

Without these habitats, they would not be able to survive to

reach their breeding and winter grounds.”

These crucial habitats have become increasingly threatened

as hurricanes like Florence have barreled through the region,

displacing birds and disrupting food supplies. Birds and hur-ricanes

have coexisted for millenia in an annual life-and-death

struggle, and survival has never come easy for birds, be they

migratory land birds, shorebirds or birds that spend most of

their time over open water.

“Pelagic seabirds that usually occur far out at sea ended

up on inland lakes as far away as Raleigh and Greensboro,”

Golder says. “After Florence, there was a Trindade petrel near

Raleigh; a brown pelican that should have been on the coast

was seen near Burlington. After Hurricane Matthew, there

was a flamingo (likely from Cuba or the Bahamas) on the

coast of S.C.,” Golder says. “During Florence, many black

skimmers that are usually around area inlets moved inland

and were reported in odd places, like on area roads, highways

and overpasses and unfortunately, some were hit by cars. I

observed a skimmer flying down the center lane of Market

Street and counted 14 dead skimmers in the vicinity of the

17-140 overpass in Porters Neck.”

While a hurricane is still over the ocean, birds will often

seek shelter in the eye and keep flying inside of it until the

storm passes over the coast, where they will take refuge on

land. It is also why birders flock to areas struck by hurricanes

— the storms provide an opportunity to spot species in places

where they are not supposed to be.

“Over the ocean, hurricanes can affect migrating birds by

directly impacting them when the birds get caught in them.

These birds can end up being carried off-course by hundreds

of miles and show up in unusual places as a result,” Addison

says. “Other birds at sea might be forced to fly around them, as

in the case of a whimbrel that was being tracked with satellites

and detoured hundreds of miles.”

Birds, however, are remarkably resilient, and they will find

ways to shield themselves from the wind and rain, seeking

shelter on the lee side of trees or buildings, in shrubbery, or

anywhere they can.

“They don’t have the Weather Channel and they really don’t

know how strong or large a storm might be. But they can

detect changes in barometric pressure and studies have shown

that they increase food intake in response to declining pressure.

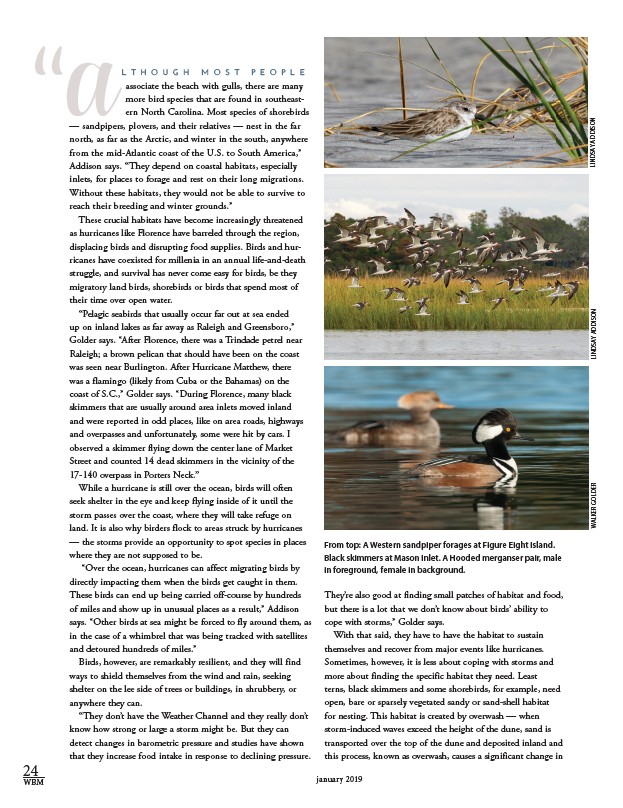

From top: A Western sandpiper forages at Figure Eight Island.

Black skimmers at Mason Inlet. A Hooded merganser pair, male

in foreground, female in background.

They’re also good at finding small patches of habitat and food,

but there is a lot that we don’t know about birds’ ability to

cope with storms,” Golder says.

With that said, they have to have the habitat to sustain

themselves and recover from major events like hurricanes.

Sometimes, however, it is less about coping with storms and

more about finding the specific habitat they need. Least

terns, black skimmers and some shorebirds, for example, need

open, bare or sparsely vegetated sandy or sand-shell habitat

for nesting. This habitat is created by overwash — when

storm-induced waves exceed the height of the dune, sand is

transported over the top of the dune and deposited inland and

this process, known as overwash, causes a significant change in

24

WBM january 2019

WALKER GOLDER LINDSAY ADDISON LINDSAY ADDISON

“a