25

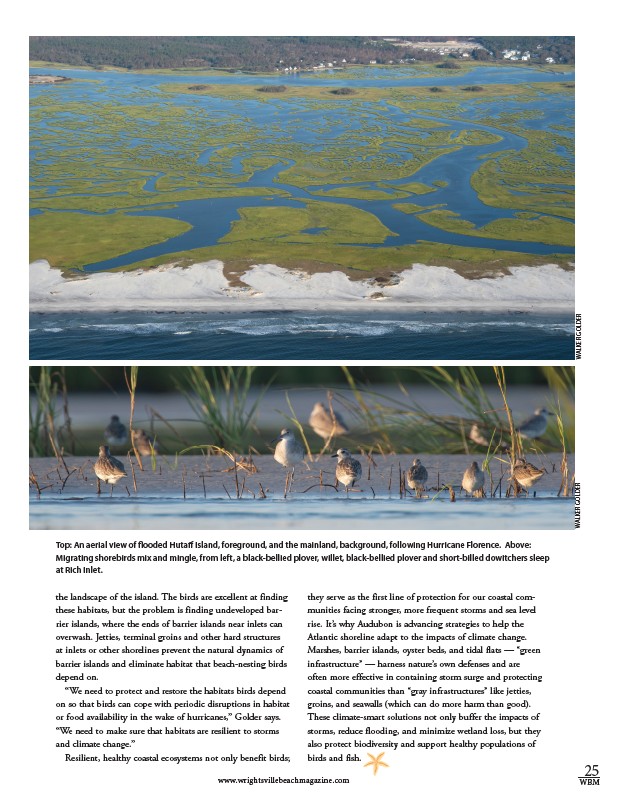

Top: An aerial view of flooded Hutaff Island, foreground, and the mainland, background, following Hurricane Florence. Above:

Migrating shorebirds mix and mingle, from left, a black-bellied plover, willet, black-bellied plover and short-billed dowitchers sleep

at Rich Inlet.

WALKER GOLDER WALKER GOLDER

the landscape of the island. The birds are excellent at finding

these habitats, but the problem is finding undeveloped bar-rier

islands, where the ends of barrier islands near inlets can

overwash. Jetties, terminal groins and other hard structures

at inlets or other shorelines prevent the natural dynamics of

barrier islands and eliminate habitat that beach-nesting birds

depend on.

“We need to protect and restore the habitats birds depend

on so that birds can cope with periodic disruptions in habitat

or food availability in the wake of hurricanes,” Golder says.

“We need to make sure that habitats are resilient to storms

and climate change.”

Resilient, healthy coastal ecosystems not only benefit birds;

they serve as the first line of protection for our coastal com-munities

facing stronger, more frequent storms and sea level

rise. It’s why Audubon is advancing strategies to help the

Atlantic shoreline adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Marshes, barrier islands, oyster beds, and tidal flats — “green

infrastructure” — harness nature’s own defenses and are

often more effective in containing storm surge and protecting

coastal communities than “gray infrastructures” like jetties,

groins, and seawalls (which can do more harm than good).

These climate-smart solutions not only buffer the impacts of

storms, reduce flooding, and minimize wetland loss, but they

also protect biodiversity and support healthy populations of

birds and fish.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM