Sonnett and Matthews

envisioned SAROS

as a means to provide

safe, clean water to

small, impoverished

communities on

remote islands and

coastal regions around

47

didn’t suck up fish or seaweed. It would take that water and pressurize it to about 150 PSI. It was designed

to send that water back to shore to a desalination system that would be located on land, but we couldn’t

get the permits to run the hoses along the bottom and set up a structure on Masonboro Island. Most of

the time the buoy was just sucking up water and spitting it back out to the ocean. When we were actually

making water and testing the desalination component, we would take our boat out and I would spend

the night out there with the desalination system in the back of the boat. We had a hose running from the

buoy to the anchored boat and made water that way.”

The prototype could produce about 300 gallons of fresh water a day in waves from 2 ½ to 3 feet.

Sonnett and Matthews were designing a commercial system that could make about 2,500 gallons a day.

The average American uses about 100 gallons a day, so the wave-powered system never was intended

to produce water on a massive scale or even to meet the needs of even a small town like Wrightsville

Beach. Instead, Sonnett and Matthews envisioned SAROS as a means to provide safe, clean water to small,

impoverished communities on remote islands and coastal regions around the world.

“Desalination consumes so much energy, and typically energy in regions that rely on desalination is

prohibitively expensive,” Sonnett says. “Our thinking was if we can replace the expensive energy source by

using the free wave energy that exists in the area where salt water is, it would be a win-win. It would be

environmentally friendly and less expensive.”

They had a system that worked and a strategy to deploy the technology, but it all fell apart when they

moved to the implementation phase. They were working with officials in Puerto Rico and Colombia to

use SAROS in remote coastal villages, but the cost of permitting and other expenses was insurmountable.

“The groundwork to set up these projects was far too expensive to justify the relatively small output of

our systems,” Sonnett says. “If our buoy was spitting out oil that would be another story. But it was spit-ting

out water, which is a pretty low-value item, even in places where water is scarce.”

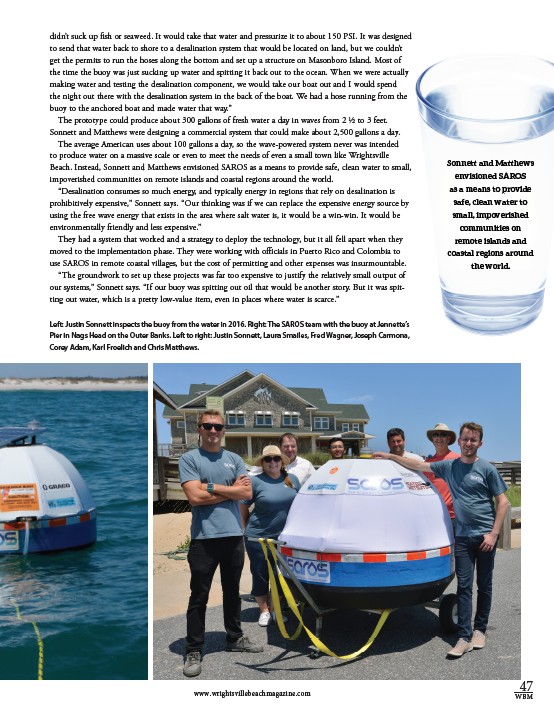

Left: Justin Sonnett inspects the buoy from the water in 2016. Right: The SAROS team with the buoy at Jennette’s

Pier in Nags Head on the Outer Banks. Left to right: Justin Sonnett, Laura Smailes, Fred Wagner, Joseph Carmona,

Corey Adam, Karl Froelich and Chris Matthews.

cutline here for

photos above and

left of WB plant.

Debit quid quatemq

uaepedia niasit

offici voloribus

maiorepuda

dollentibea volorro

od exerum eossitia

et volore sus dem

entur?

the world.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM