handful of sand and sprinkled it on the steak. I can see Daddy right

now. He stuck a fork in it and ran out in the surf to wash it off.”

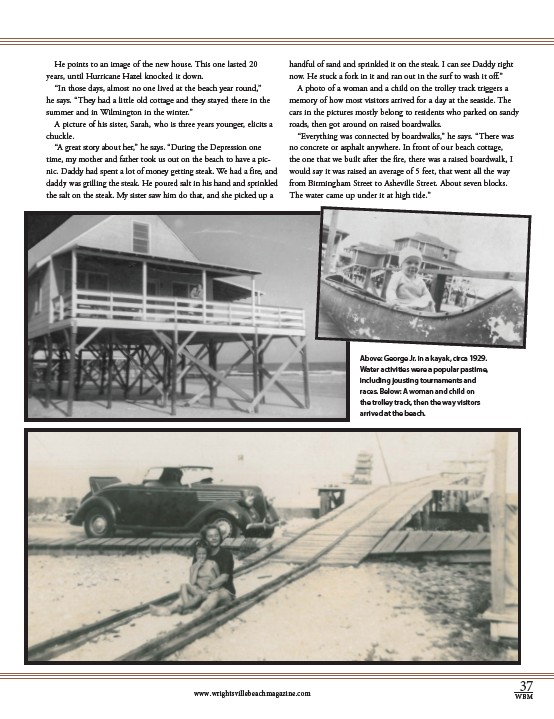

A photo of a woman and a child on the trolley track triggers a

memory of how most visitors arrived for a day at the seaside. The

cars in the pictures mostly belong to residents who parked on sandy

roads, then got around on raised boardwalks.

“Everything was connected by boardwalks,” he says. “There was

no concrete or asphalt anywhere. In front of our beach cottage,

the one that we built after the fire, there was a raised boardwalk, I

would say it was raised an average of 5 feet, that went all the way

from Birmingham Street to Asheville Street. About seven blocks.

The water came up under it at high tide.”

37

He points to an image of the new house. This one lasted 20

years, until Hurricane Hazel knocked it down.

“In those days, almost no one lived at the beach year round,”

he says. “They had a little old cottage and they stayed there in the

summer and in Wilmington in the winter.”

A picture of his sister, Sarah, who is three years younger, elicits a

chuckle.

“A great story about her,” he says. “During the Depression one

time, my mother and father took us out on the beach to have a pic-nic.

Daddy had spent a lot of money getting steak. We had a fire, and

daddy was grilling the steak. He poured salt in his hand and sprinkled

the salt on the steak. My sister saw him do that, and she picked up a

Above: George Jr. in a kayak, circa 1929.

Water activities were a popular pastime,

including jousting tournaments and

races. Below: A woman and child on

the trolley track, then the way visitors

arrived at the beach.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM