IS ESCAPE sounds like something

from a spy novel.

With the prisons full to overflowing,

some were let go with posting a surety

bond, including Fred. Friends helped

smuggle him out of Tehran and hid him

in a remote area. He then went by bus

to the Iran-Pakistan border. With a fake ID and passport

obtained through his international connections, he walked

across the border to freedom. From there, he made his way

to Karachi, where he boarded a flight to Germany. He went

to the American embassy in Bonn and applied for political

asylum. And called his wife.

“One day, after three years, I had a phone call,” Pat says.

“It was Fred. I was so happy. It was the best day of my life.”

ALONE IN ARKANSAS

While Fred was going through the hell of imprisonment,

enduring physical and mental torture before his escape

from almost certain death, Pat was living through her own

purgatory.

She and the children left in the summer of 1978, as the

turmoil in Iran was building.

She bought a small flat on Baker Street in London. The

children were enrolled in school.

“That was the most important thing, for the children to

be educated,” she says.

But everything else was uncertain.

“I didn’t have any news from Fred,” she says. “I couldn’t

get any news from anybody. It was really frightening.”

Her money was running out, as was her visa to stay in

the U.K. One of her brothers was in Fayetteville, studying

architecture at the University of Arkansas. Pat and the chil-dren

packed for America.

“After one year in England, I said it is much better to

go to the United States,” she says. “At least they have free

schools there.”

With money from the sale of the flat in London, she

bought a house in Arkansas.

“I bought a very small house,” she says. “I put a big fence

around it and two Dobermans in order to take care of the

children. I bought a .22 gun in order to protect myself.”

After the opulent family life in Tehran and the cosmo-politan

66

WBM february 2018

culture of London, Arkansas felt like the middle

of nowhere. It was difficult to adjust, especially during

the hostage crisis when anti-Iranian sentiment in America

peaked.

“From Tehran to London to Fayetteville, Arkansas, that

is a very strange trip,” Shawn says. “I always tell everybody,

it’s never how bad things are for you, it’s how far you have

fallen. I was driven to school with a chauffeured Mercedes

Benz when I was 9 years old. Talk about being spoiled

rotten. Now we were in a little bitty ranch house, with a

6-foot chain link fence around it. You’re riding the yellow

school bus that’s nasty and smelly with tobacco chew to a

junior high school and high school where ignorance and

prejudice and discrimination is at its highest. I was the only

Iranian, the only Persian kid in the school. It was a very

rough patch.”

It was a desperate time. Pat spoke very little English,

making it challenging to find work. Everything they once

had was lost, seized by the militants. Money trickled in,

gifts from family and friends, but it didn’t go far.

“I took Shahrzad to the mall once and she said, ‘Mom, I

want that dress. It is beautiful,’” Pat says. “I said, ‘I know,

H

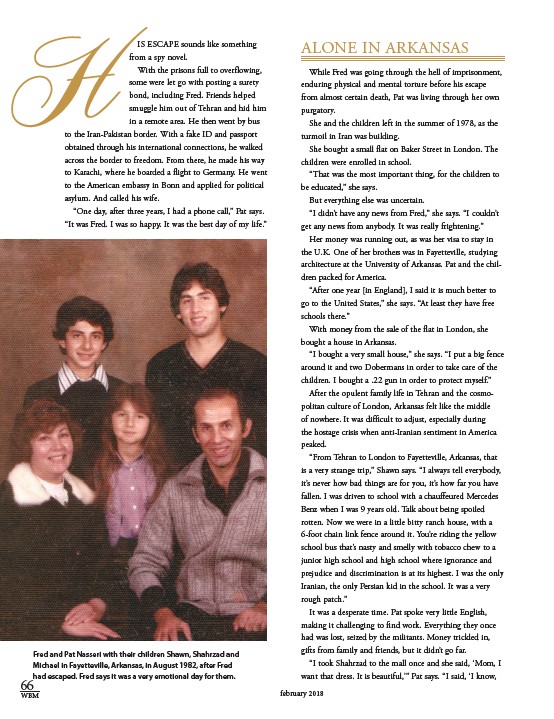

Fred and Pat Nasseri with their children Shawn, Shahrzad and

Michael in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in August 1982, after Fred

had escaped. Fred says it was a very emotional day for them.