“There are many

opportunities

for creativity:

carving, sculpture,

piercing, staining,

and painting,”

she says. LeGwin,

whose father was

a woodworker,

maintains anyone

can learn to turn

wood.

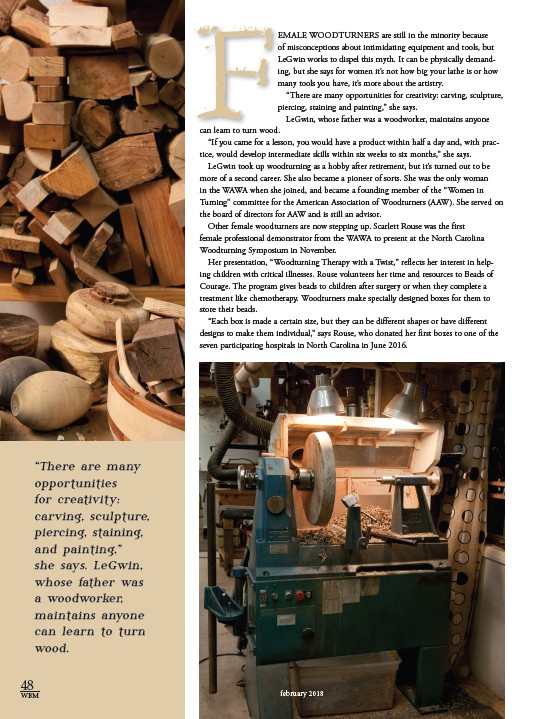

EMALE WOODTURNERS are still in the minority because

of misconceptions about intimidating equipment and tools, but

LeGwin works to dispel this myth. It can be physically demand-ing,

but she says for women it’s not how big your lathe is or how

many tools you have, it’s more about the artistry.

“There are many opportunities for creativity: carving, sculpture,

piercing, staining and painting,” she says.

LeGwin, whose father was a woodworker, maintains anyone

can learn to turn wood.

“If you came for a lesson, you would have a product within half a day and, with prac-tice,

would develop intermediate skills within six weeks to six months,” she says.

LeGwin took up woodturning as a hobby after retirement, but it’s turned out to be

more of a second career. She also became a pioneer of sorts. She was the only woman

in the WAWA when she joined, and became a founding member of the “Women in

Turning” committee for the American Association of Woodturners (AAW). She served on

the board of directors for AAW and is still an advisor.

Other female woodturners are now stepping up. Scarlett Rouse was the first

female professional demonstrator from the WAWA to present at the North Carolina

Woodturning Symposium in November.

Her presentation, “Woodturning Therapy with a Twist,” reflects her interest in help-ing

children with critical illnesses. Rouse volunteers her time and resources to Beads of

Courage. The program gives beads to children after surgery or when they complete a

treatment like chemotherapy. Woodturners make specially designed boxes for them to

store their beads.

“Each box is made a certain size, but they can be different shapes or have different

designs to make them individual,” says Rouse, who donated her first boxes to one of the

seven participating hospitals in North Carolina in June 2016.

48

WBM february 2018