“Quail hunting’s not a team sport,”

says Ricky Kelly.

“All of us go together as a group, walking. You’re walking around the whole time looking

for the birds, the dogs are looking for the birds, and the dogs go with you.”

Kelly, who has been Genteel’s caretaker for the last 27 years, is also Harrelson’s personal

hunting guide. He raises quail from day-old chicks, turning them loose about seven weeks

later into food plots that provide both food and shelter for the covey. Kelly also trains the

plantation’s five English setters and four English pointers along with his two Labrador

retrievers, Bullet, now retired, and Ellie May, a pup. He says, the dogs, after a little while,

know the route as well as he does.

“I’m going to park the truck and walk in a giant circle and back to the truck,” Kelly

says, “hunting all the food plots that are all over this property. We find the dog on point.

We go to the dog, he’s pointed birds. He doesn’t see them, he smells them. I’m going to

be in the middle because I’m not shooting,” Kelly says.

“We’re spread out a little bit,” Harrelson says. “The fellow on the right does not shoot

a bird coming up on the left hand side. You leave it alone. It’s not your territory; it’s not

your bird. Most good quail hunters are very gentlemanly about it.”

Using mostly double barreled or split barreled 12 gauge shotguns, quail hunters shoot

away from the circle’s center, leaving Kelly to train his eyes on the birds’ flight patterns.

“They come up and go straight away,” Kelly says. “They might not fly that high

off the ground this time. And the next one might fly 15, 20 feet off the ground. So you

never know.”

As the shoot progresses, Kelly says, “I’m looking at where all the birds are going that didn’t

get shot at. We try to chase down some of the singles. You call them singles after they’ve

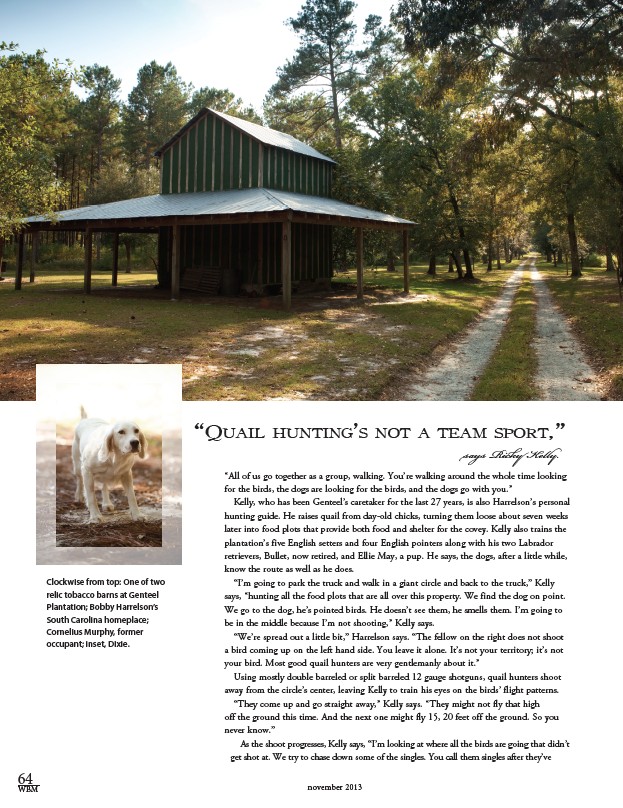

Clockwise from top: One of two

relic tobacco barns at Genteel

Plantation; Bobby Harrelson’s

South Carolina homeplace;

Cornelius Murphy, former

occupant; inset, Dixie.

64

WBM november 2013