After studying pottery in Montana, Steve Kelly apprenticed at Buckcreek Pottery in Nelson, Virginia. There, he immersed himself

in the Japanese tradition of mingei.

“Philosopher Yanagi Sōetsu is the grandfather of this tradition,” he says. “Mingei states if you do something enough, the object you

make will have an inherent presence that shows a knowledgeable hand. Sōetsu used this example of a rice bowl he found in Korea. It was

made in these factories with not much thought, but there was this inherent beauty. It was perfect but not overly fussy. My apprenticeship

and early works were very rooted in this. Yet, today, the pots I make don’t look very mingei.”

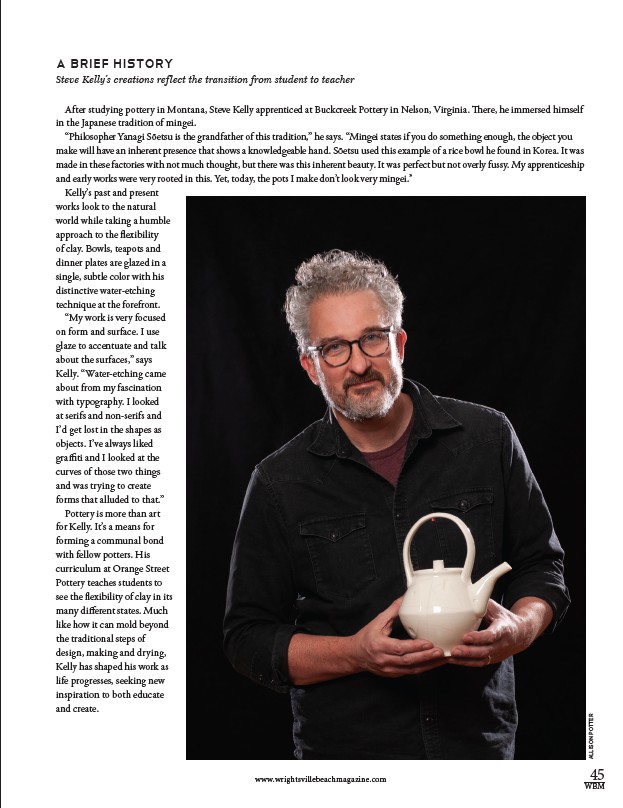

Kelly’s past and present

works look to the natural

world while taking a humble

approach to the flexibility

of clay. Bowls, teapots and

dinner plates are glazed in a

single, subtle color with his

distinctive water-etching

technique at the forefront.

“My work is very focused

on form and surface. I use

glaze to accentuate and talk

about the surfaces,” says

Kelly. “Water-etching came

about from my fascination

with typography. I looked

at serifs and non-serifs and

I’d get lost in the shapes as

objects. I’ve always liked

graffiti and I looked at the

curves of those two things

and was trying to create

forms that alluded to that.”

Pottery is more than art

for Kelly. It’s a means for

forming a communal bond

with fellow potters. His

curriculum at Orange Street

Pottery teaches students to

see the flexibility of clay in its

many different states. Much

like how it can mold beyond

the traditional steps of

design, making and drying,

Kelly has shaped his work as

life progresses, seeking new

inspiration to both educate

and create.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com 45

WBM

A Brief History

Steve Kelly’s creations reflect the transition from student to teacher

ALLISON POTTER