COASTLINE OPTIONS

STORM surges and large waves cause property damage

and beach erosion on a nearly annual basis. A study

published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration predicts a substantial increase in storm

damage in the future. “The large increases in tropical Atlantic Sea

surface temperatures projected for the late 21st century would

imply very substantial increases in hurricane destructive potential

— roughly a 300 percent increase by 2100.”

In places including Hawaii and Southern California, a network

of outer reefs acts as a safety net, dissipating wave energy, which

protects the shoreline. Most of the time, those reefs are invisible to

the naked eye, until a major swell event hits the coast. Then waves

can be seen breaking a long way out in places where the water is

typically calm.

“After watching powerful waves chew away at the sandy coastlines

along the East Coast, one might wonder how tropical islands manage

relentless swells without severe erosion,” says Dan Ginolfi, director of

coastal resilience for Coastal Strategies, a consulting firm for beach

nourishment and dredging projects, aquatic ecosystem restoration,

the Corps of Engineers, the Federal Emergency Management

Agency, and many others.

“The reason these islands are still here today is they all have one

thing in common — offshore reefs to dissipate wave energy.”

This is a strong contrast to a major swell event on the East Coast,

where large waves resulting from long-period swells usually break all

at once near the coastline. Surfers call this phenomenon a “close-out.”

Since it is practically impossible to ride in any direction other than

straight, the surfer is effectively closed-out from making the wave.

Large waves marching forward unimpeded and breaking near the

beach pose a danger for swimmers and boaters. Smaller is preferable

from a safety standpoint.

“There are reef breaks worldwide where 20-plus-foot surf is

occurring a quarter-mile offshore, but the waves reaching the

beach are small and playful,” Ginolfi says.

A network of outer reefs can protect the inner reefs as well as

the waters inside lagoons. There are those within the coastal

community advocating artificial reefs as a key component of a

coastal protection strategy.

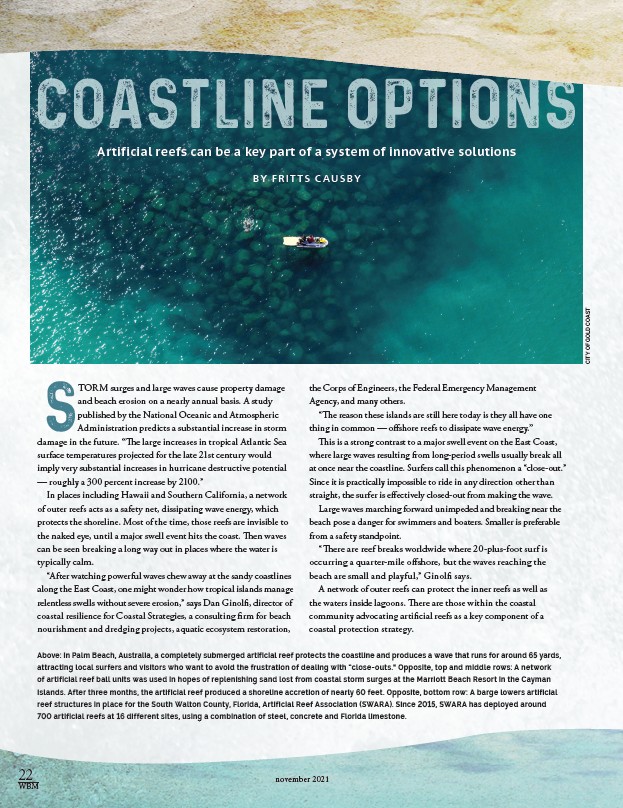

Above: In Palm Beach, Australia, a completely submerged artificial reef protects the coastline and produces a wave that runs for around 65 yards,

attracting local surfers and visitors who want to avoid the frustration of dealing with “close-outs.” Opposite, top and middle rows: A network

of artificial reef ball units was used in hopes of replenishing sand lost from coastal storm surges at the Marriott Beach Resort in the Cayman

Islands. After three months, the artificial reef produced a shoreline accretion of nearly 60 feet. Opposite, bottom row: A barge lowers artificial

reef structures in place for the South Walton County, Florida, Artificial Reef Association (SWARA). Since 2015, SWARA has deployed around

700 artificial reefs at 16 different sites, using a combination of steel, concrete and Florida limestone.

CITY OF GOLD COAST

Artificial reefs can be a key part of a system of innovative solutions

BY FRITTS CAUSBY

22 november 2021

WBM