MUCH OF THE HISTORY was preserved in a museum established at the Hannah Block USO

Building in downtown Wilmington, which itself was an important part of the war effort. From 1941 to

1945, about 35,000 uniformed personnel a week came to town for dancing, recreation and entertainment.

As Jones considered the area’s vast involvement, the germ of an idea began to grow. Wilmington should

be recognized for its World War II legacy.

“I came up with the idea in late 2007,” he says. “When 2008 began, I began contacting the city council

and county commissioners about proclaiming Wilmington as a heritage city.”

Those efforts quickly bore fruit. The city and county

governments issued official declarations recognizing

Wilmington as a World War II City.

It was a good start, but Jones wanted national recogni-tion.

38

WBM november 2020

To accomplish that, he had to wade into the murky

waters of the legislative process.

“It was a classic case study of how to get things done

through Congress,” Jones says. “It was an amazing coop-erative

effort from volunteers, elected officials, govern-ment

staff, the media, and our congressional delegation.”

Jones, a former assistant to Republican President

Gerald Ford, began by working with U.S. Rep. Mike

McIntyre, a Democrat. They established the criteria

— what did your city do to support the war effort, and

what are your efforts to preserve that history — and

created the first draft of what would become the legis-lation.

In the beginning Jones also worked with Gov. Bev

Perdue, Sen. Kay Hagan and N.C. Rep. Susi Hamilton,

all Democrats, and Sen. Richard Burr, a Republican. Burr

helped for several years, then turned it over to Tillis, a

Republican. Rouzer, a Republican, took the torch when

he was elected in 2014 following McIntyre’s retirement.

The effort started when George W. Bush was president,

continued during Barack Obama’s tenure, and finally

happened during the Trump administration.

“It was totally bipartisan,” Jones says. “It was never

intended to be political or partisan. I didn’t give a hoot

or holler who was in the White House. I just wanted the

president to come to Wilmington and sign the declaration

on the Battleship North Carolina.”

It took so long because it had never been done. When

Jones first approached McIntyre with the idea, he was

hoping for something as simple as a congressional declara-tion.

He learned it had to be done through the legislative

process, which entailed creating the criteria for a munici-pality

to seek recognition as a WWII Heritage City.

Jones made several trips to Washington, testifying

twice before congressional committees.

“This entire project has taken an enormous amount of

patience,” he says. “I’m a volunteer. I never had a position

of authority. I had no pull, no leverage. In my later years

— I’m now 86 — I’ve acquired at least the ability to realize

when one should keep one’s mouth shut and look for the

right opportunity. I had to be extremely diplomatic and

patient.”

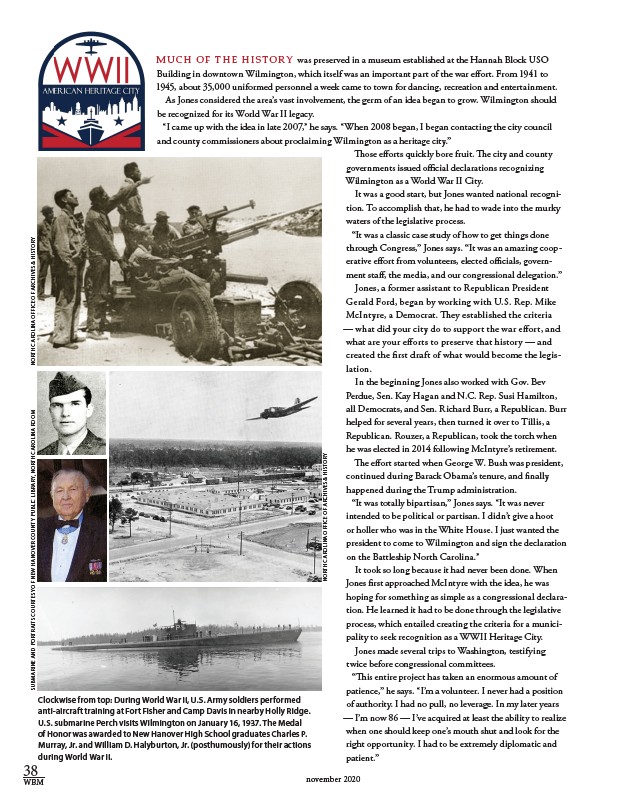

Clockwise from top: During World War II, U.S. Army soldiers performed

anti-aircraft training at Fort Fisher and Camp Davis in nearby Holly Ridge.

U.S. submarine Perch visits Wilmington on January 16, 1937. The Medal

of Honor was awarded to New Hanover High School graduates Charles P.

Murray, Jr. and William D. Halyburton, Jr. (posthumously) for their actions

during World War II.

SUBMARINE AND PORTRAITS COURTESY OF NEW HANOVER COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY, NORTH CAROLINA ROOM NORTH CAROLINA OFFICE OF ARCHIVES & HISTORY

NORTH CAROLINA OFFICE OF ARCHIVES & HISTORY