33

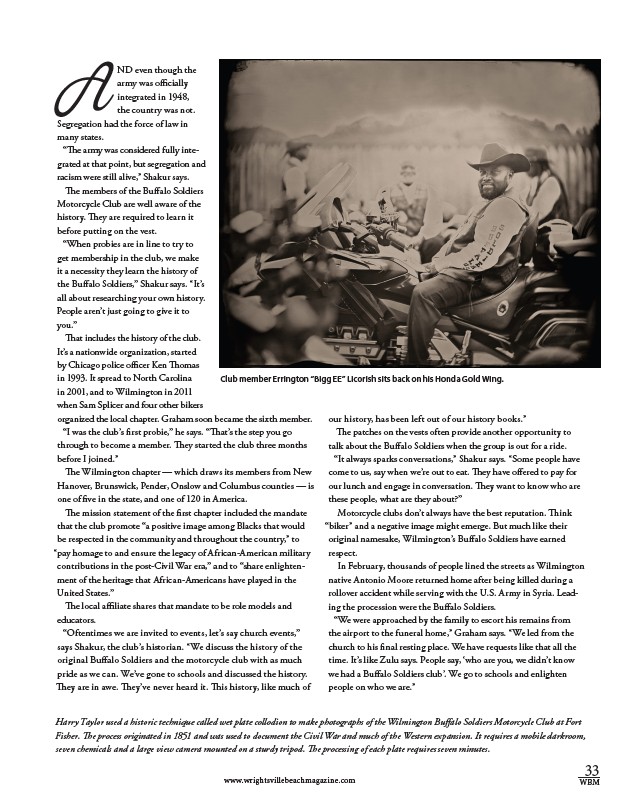

Club member Errington “Bigg EE” Licorish sits back on his Honda Gold Wing.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM

ND even though the

army was officially

integrated in 1948,

the country was not.

A

Segregation had the force of law in

many states.

“The army was considered fully inte-grated

at that point, but segregation and

racism were still alive,” Shakur says.

The members of the Buffalo Soldiers

Motorcycle Club are well aware of the

history. They are required to learn it

before putting on the vest.

“When probies are in line to try to

get membership in the club, we make

it a necessity they learn the history of

the Buffalo Soldiers,” Shakur says. “It’s

all about researching your own history.

People aren’t just going to give it to

you.”

That includes the history of the club.

It’s a nationwide organization, started

by Chicago police officer Ken Thomas

in 1993. It spread to North Carolina

in 2001, and to Wilmington in 2011

when Sam Splicer and four other bikers

organized the local chapter. Graham soon became the sixth member.

“I was the club’s first probie,” he says. “That’s the step you go

through to become a member. They started the club three months

before I joined.”

The Wilmington chapter — which draws its members from New

Hanover, Brunswick, Pender, Onslow and Columbus counties — is

one of five in the state, and one of 120 in America.

The mission statement of the first chapter included the mandate

that the club promote “a positive image among Blacks that would

be respected in the community and throughout the country,” to

“pay homage to and ensure the legacy of African-American military

contributions in the post-Civil War era,” and to “share enlighten-ment

of the heritage that African-Americans have played in the

United States.”

The local affiliate shares that mandate to be role models and

educators.

“Oftentimes we are invited to events, let’s say church events,”

says Shakur, the club’s historian. “We discuss the history of the

original Buffalo Soldiers and the motorcycle club with as much

pride as we can. We’ve gone to schools and discussed the history.

They are in awe. They’ve never heard it. This history, like much of

our history, has been left out of our history books.”

The patches on the vests often provide another opportunity to

talk about the Buffalo Soldiers when the group is out for a ride.

“It always sparks conversations,” Shakur says. “Some people have

come to us, say when we’re out to eat. They have offered to pay for

our lunch and engage in conversation. They want to know who are

these people, what are they about?”

Motorcycle clubs don’t always have the best reputation. Think

“biker” and a negative image might emerge. But much like their

original namesake, Wilmington’s Buffalo Soldiers have earned

respect.

In February, thousands of people lined the streets as Wilmington

native Antonio Moore returned home after being killed during a

rollover accident while serving with the U.S. Army in Syria. Lead-ing

the procession were the Buffalo Soldiers.

“We were approached by the family to escort his remains from

the airport to the funeral home,” Graham says. “We led from the

church to his final resting place. We have requests like that all the

time. It’s like Zulu says. People say, ‘who are you, we didn’t know

we had a Buffalo Soldiers club’. We go to schools and enlighten

people on who we are.”

Harry Taylor used a historic technique called wet plate collodion to make photographs of the Wilmington Buffalo Soldiers Motorcycle Club at Fort

Fisher. The process originated in 1851 and was used to document the Civil War and much of the Western expansion. It requires a mobile darkroom,

seven chemicals and a large view camera mounted on a sturdy tripod. The processing of each plate requires seven minutes.