45

Coming Together to Protect and Preserve

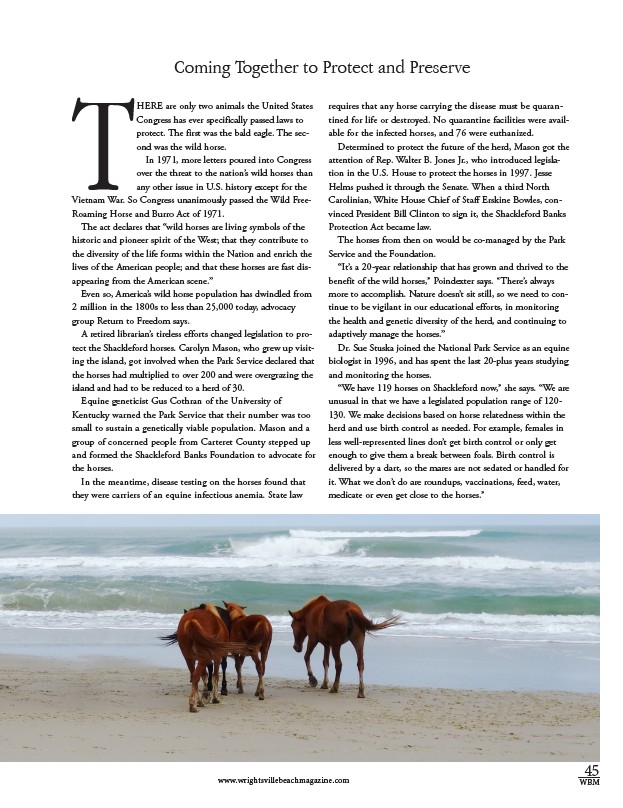

THERE are only two animals the United States

Congress has ever specifically passed laws to

protect. The first was the bald eagle. The sec-ond

was the wild horse.

In 1971, more letters poured into Congress

over the threat to the nation’s wild horses than

any other issue in U.S. history except for the

Vietnam War. So Congress unanimously passed the Wild Free-

Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971.

The act declares that “wild horses are living symbols of the

historic and pioneer spirit of the West; that they contribute to

the diversity of the life forms within the Nation and enrich the

lives of the American people; and that these horses are fast dis-appearing

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM

from the American scene.”

Even so, America’s wild horse population has dwindled from

2 million in the 1800s to less than 25,000 today, advocacy

group Return to Freedom says.

A retired librarian’s tireless efforts changed legislation to pro-tect

the Shackleford horses. Carolyn Mason, who grew up visit-ing

the island, got involved when the Park Service declared that

the horses had multiplied to over 200 and were overgrazing the

island and had to be reduced to a herd of 30.

Equine geneticist Gus Cothran of the University of

Kentucky warned the Park Service that their number was too

small to sustain a genetically viable population. Mason and a

group of concerned people from Carteret County stepped up

and formed the Shackleford Banks Foundation to advocate for

the horses.

In the meantime, disease testing on the horses found that

they were carriers of an equine infectious anemia. State law

requires that any horse carrying the disease must be quaran-tined

for life or destroyed. No quarantine facilities were avail-able

for the infected horses, and 76 were euthanized.

Determined to protect the future of the herd, Mason got the

attention of Rep. Walter B. Jones Jr., who introduced legisla-tion

in the U.S. House to protect the horses in 1997. Jesse

Helms pushed it through the Senate. When a third North

Carolinian, White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles, con-vinced

President Bill Clinton to sign it, the Shackleford Banks

Protection Act became law.

The horses from then on would be co-managed by the Park

Service and the Foundation.

“It’s a 20-year relationship that has grown and thrived to the

benefit of the wild horses,” Poindexter says. “There’s always

more to accomplish. Nature doesn’t sit still, so we need to con-tinue

to be vigilant in our educational efforts, in monitoring

the health and genetic diversity of the herd, and continuing to

adaptively manage the horses.”

Dr. Sue Stuska joined the National Park Service as an equine

biologist in 1996, and has spent the last 20-plus years studying

and monitoring the horses.

“We have 119 horses on Shackleford now,” she says. “We are

unusual in that we have a legislated population range of 120-

130. We make decisions based on horse relatedness within the

herd and use birth control as needed. For example, females in

less well-represented lines don’t get birth control or only get

enough to give them a break between foals. Birth control is

delivered by a dart, so the mares are not sedated or handled for

it. What we don’t do are roundups, vaccinations, feed, water,

medicate or even get close to the horses.”