President Lincoln's Naval Blockade

President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a

naval blockade of the seceded southern states

on April 19, 1861, only five days after the fall of

Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina, to

Confederate forces. He revised the blockade on

April 27 to include Virginia and North Carolina,

although the Tar Heel state was still in the Union

and did not go out until May 20, 1861. Lincoln

realized that the South did not possess the

industrial capacity to manufacture large quantities

of war materials to sustain a war effort and

would turn to Europe for help. He intended for

foreign nations, especially Great Britain, which

depended heavily on the importation of southern

grown cotton to fuel its cloth industry, to

stay out of the ensuing American conflict. Queen

Victoria of England and other heads of state

agreed to respect the blockade, but they turned

a blind eye to the profitable smuggling trade

that soon began in association with Confederate

merchants and importers.

The US Navy faced many challenges in the

spring of 1861 to establish the blockade. Only

12 steamships out of 42 commissioned vessels

were available for immediate service to guard

3,549 miles of coastline from Virginia to Texas.

As a testament to Yankee ingenuity, that

motley array of vessels had grown to 671 ships

by war’s end. Two out of every three Union

vessels saw duty on the blockade. Despite its

exponential growth, the navy failed to prevent

many commerce vessels from carrying supplies

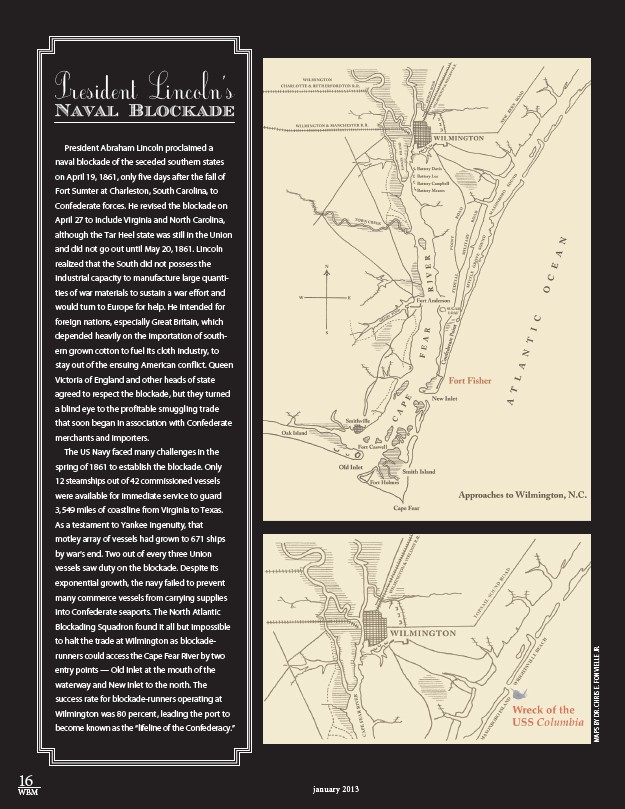

into Confederate seaports. The North Atlantic

Blockading Squadron found it all but impossible

to halt the trade at Wilmington as blockade-

runners could access the Cape Fear River by two

entry points — Old Inlet at the mouth of the

waterway and New Inlet to the north. The

success rate for blockade-runners operating at

Wilmington was 80 percent, leading the port to

become known as the “lifeline of the Confederacy.”

16

WBM january 2013

maps by Dr. Chris E. Fonvielle Jr.