Coastline Options

Artificial reefs can be a key part of a system of innovative solutions

BY Fritts Causby

Storm surges and large waves cause property damage and beach erosion on a nearly annual basis. A study published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts a substantial increase in storm damage in the future. “The large increases in tropical Atlantic Sea surface temperatures projected for the late 21st century would imply very substantial increases in hurricane destructive potential — roughly a 300 percent increase by 2100.”

In places including Hawaii and Southern California, a network of outer reefs acts as a safety net, dissipating wave energy, which protects the shoreline. Most of the time, those reefs are invisible to the naked eye, until a major swell event hits the coast. Then waves can be seen breaking a long way out in places where the water is typically calm.

“After watching powerful waves chew away at the sandy coastlines along the East Coast, one might wonder how tropical islands manage relentless swells without severe erosion,” says Dan Ginolfi, director of coastal resilience for Coastal Strategies, a consulting firm for beach nourishment and dredging projects, aquatic ecosystem restoration, the Corps of Engineers, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and many others.

“The reason these islands are still here today is they all have one thing in common — offshore reefs to dissipate wave energy.”

This is a strong contrast to a major swell event on the East Coast, where large waves resulting from long-period swells usually break all at once near the coastline. Surfers call this phenomenon a “close-out.” Since it is practically impossible to ride in any direction other than straight, the surfer is effectively closed-out from making the wave.

Large waves marching forward unimpeded and breaking near the beach pose a danger for swimmers and boaters. Smaller is preferable from a safety standpoint.

“There are reef breaks worldwide where 20-plus-foot surf is occurring a quarter-mile offshore, but the waves reaching the beach are small and playful,” Ginolfi says.

A network of outer reefs can protect the inner reefs as well as the waters inside lagoons. There are those within the coastal community advocating artificial reefs as a key component of a coastal protection strategy.

On the East Coast, the heavy machinery and trucks that are required for beach nourishment projects are a common sight. For outsiders, it can be hard to understand why the value and cost effectiveness of beach nourishment never seems to be questioned. Those who work in coastal preservation daily have more insight.

“Beach nourishment and temporary sandbags are simply the only options in the toolbox that can be permitted right now,” says Randy Boyd, principle of Scenic Consulting Group, an environmental and coastal engineering service. “There needs to be a platform for testing innovative, potentially transformative new technologies.”

Innovative technologies are something the company is familiar with, as it was a finalist in the 2020 North Carolina Tech awards in the Industry Driven-Clean Tech category. It was also recently included in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “Engineering with Nature” atlas. The company has a variety of successful projects under its belt, including a project to protect the shoreline at Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson.

The historic site and its Colonial-era wharves were at risk from constant tidal forces and dynamic wave action. Important historical artifacts were being washed into the Cape Fear River, and the erosion was destroying valuable coastal resources. Scenic Consulting Group installed 220 feet of Reefmaker, a living shoreline wave attenuation system, along the area with the highest erosion. The second phase installed an additional 240 feet — just before Hurricane Florence hit the North Carolina coast in 2018.

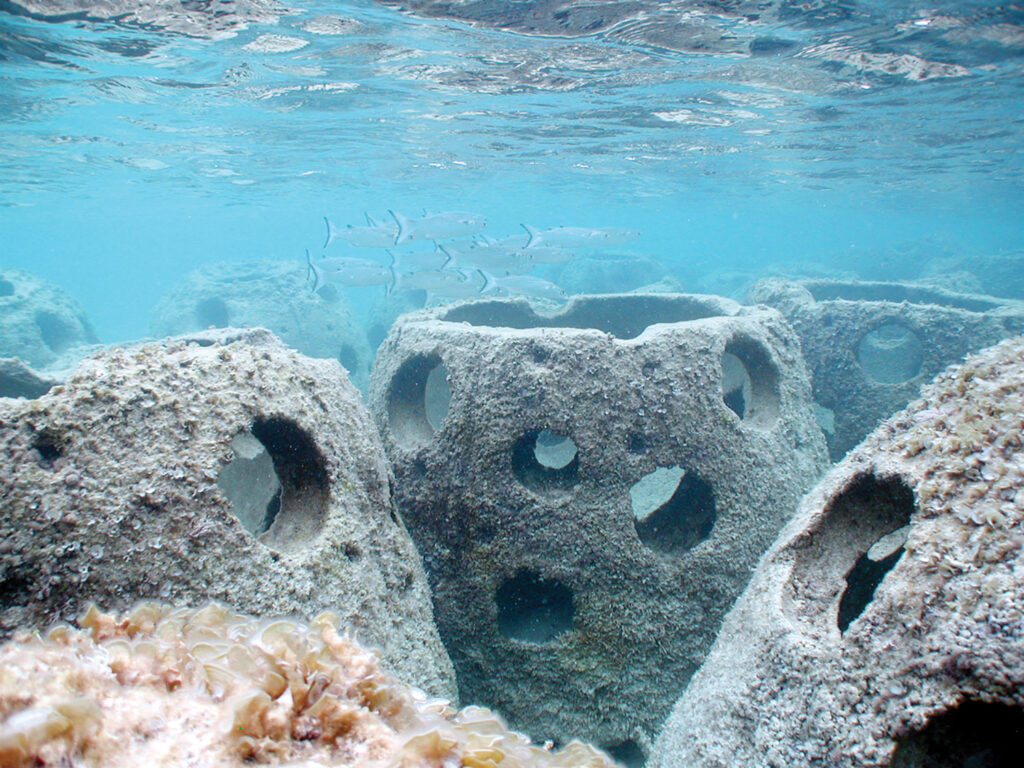

The Reefmaker is designed to mitigate coastal erosion. The system utilizes flow-through technology to dissipate wave energy by reflecting it back into open water from the front face of the structure, ensuring wave collisions occur along the sides of the octagonal structure, and by dissipating water energy.

The system stabilizes the shoreline and marsh while enhancing the fish and shellfish habitat on and around the structure for marine fauna, sessile and non-sessile organisms.

“This system has not only proven to protect our delicate coastal ecosystems, but it is helping those ecosystems to thrive, where some were nearly destroyed,” Boyd says. “It’s been encouraging to see everything from river otters, fish and seabirds, to oysters, crabs and shoreline marsh grass thrive in this new, engineered habitat. And it’s important to note we didn’t reintroduce a species or plant anything, we simply created the conditions that are conducive to growth.”

Beach nourishment projects appear to be an essential strategy for shoring up the economy and ensuring tourism dollars continue to flow. But beach nourishment — dredging sand from other areas and funneling it onto the beach — is not optimal for marine life.

Inefficient from an economic standpoint, renourishment must be done every few years to remain effective. Repairs post hurricanes Florence and 2016’s Matthew to Carolina and Kure beaches combined with the scheduled nourishment received total funding of more than $17 million. Though officials touted it as a highly successful means of protecting the shoreline, particularly from the destructive impact of hurricanes, others claim that artificial reefs would be at least as effective while offering a considerable savings.

“A ‘living’ artificial reef deployment is very economic given the consistent rise in global sea surface elevation,” says Stephen Rodan, president of the Beyond Coral Foundation and inventor of CHARM, an automated robot designed to help restore coral reefs. “Some reefs are able to grow in volume, which provides a positive economic return for investment. In certain cases, a living reef might rise in effective height at the same rate as (or greater than) the mean rise in global sea surface height (3.4 + 0.6 mm/year), which is very promising.”

A Different Solution

Advocates says artificial reefs have the potential to make beach renourishment obsolete. They argue, in addition to protecting against the adverse impacts of hurricanes and creating a safe harbor for wildlife, they can create popular surf and diving spots.

The North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries (NCDMF) has already constructed a network of 42 artificial reefs in the ocean and 22 in estuaries. The purpose is to provide a spawning and foraging habitat for many species of fish and to establish oyster sanctuaries.

“Artificial reef projects can aid in the recovery and preservation of coastal populations through the maintenance and establishment of a nursery at the desired site,” Rodan says.

Another goal is to compensate for the destruction of coastal habitats and the reduction of water quality. A side benefit is an expansion of recreational diving.

The NCDMF used a variety of old boats to build the reefs. The scuttled vessels consist of everything from trawlers and fishing boats to barges, dredgers and sailboats, and even a few old Navy ships that saw action in World War II, the Korean War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, creating many areas of interest for divers.

A study commissioned by the board of county commissioners in Citrus County, Florida, found that the average cost of building an artificial reef was in the tens of thousands of dollars, significantly less than beach nourishment projects.

The study said the network of artificial reefs in the Florida Panhandle has an economic impact of $415 million per year.

In addition to creating healthy fish populations and attracting divers, a network of artificial reefs would be a positive for surfers. A major swell event draws a crowd, so creating new surf spots has the potential to generate a positive impact on local economies. A recent report published by Surf-First and the Surfrider Foundation shows that surfers visit the beach around 100 times a year, spending approximately $66 each trip. This equates to a more than $36 million annual contribution.

At the Marriott beach resort in the Cayman Islands a network of artificial reef ball units was placed in front of the resort in hopes of replenishing a section of the beach lost to coastal storm surges.

After three months, the artificial reef had produced a shoreline accretion of 18 meters. After four years, the beach was almost completely restored.

Rodan says artificial reefs can be an effective means of ensuring coastal resilience.

“A new reef’s physical characteristics will produce a considerable drag on each incoming wave; slowing the wave’s speed, shortening the wave’s period, and causing the wave to break prematurely,” he says. “This condition, combined with the gentle slope of the seafloor, should result in a more ‘crumbly’ and less powerful wave reaching shore.”

Australia, one of the most surf-crazed nations on the planet, has a functional artificial surfing reef. The project began in 2013 when the city of Gold Coast realized that something needed to be done to protect the area from erosion.

After four years of testing, project teams chose building an artificial reef. After pumping sand to grow the beach, they created the artificial reef to keep the sand in place.

The approximately 175-by-87 yard reef was completed in 2019 for a cost of around $12.5 million. The design channels swell energy into a continuous and predictable wave that runs for around 65 yards, more on a good day. Video of the wave, which started with refining an underwater submerged breakwater into a shape that refracts swell energy into a shallow crest, is available online.

Palm Beach County, Florida, has been creating artificial reefs for 40 years. Using materials including limestone, concrete and decommissioned ships, the county has provided an arena for diving, snorkeling and fishing. Along with creating a spawning habitat for marine life, the reefs provide around 1,800 jobs and generate substantial funds for the economy.

“These habitats provide protection from predation and serve as recovery zones for all sorts of ocean life,” Rodan says. “A complex and varied reef architecture is essential for creating a sustainable and balanced ecosystem.”

Just off the coast at South Beach in Miami, the proposed Reef Line will be a public sculpture park, snorkel trail, and artificial reef. The project, which will run for roughly nine miles when complete, is intended to provide a habitat for marine life, promote biodiversity, and increase coastal resilience.

It will include eco-friendly artworks from around the world. An open call is out for artists to submit their plans for sculptures and reef modules. As stated on the website by founder/art director Ximena Caminos, “This series of artist-designed and scientist-informed artificial reefs will demonstrate how tourism, artistic expression, and the creation of critical habitat can be aligned.”

Advocates see artificial reefs as an environmentally friendly alternative to beach nourishment.

A network of artificial reefs would be less expensive, last longer, provide a haven for wildlife, and potentially generate a significant amount of annual revenue, which could then be used to fund other projects that are sorely in need.

“We are confident that, with some modifications and testing, the technology we have proven effective in inland estuaries could be applied to offshore installations,” Boyd says.