The mystery of the William H. Sumner Uncovered

Suicide or murder in grounding of ship

BY Pam Creech

Originally published in the February 2010 issue of Wrightsville Beach Magazine.

Nearly 100 years ago, beachgoers enjoying a late summer afternoon at Wrightsville Beach spotted a large ship on the horizon. Those with nautical experience noted the vessel was dangerously close to shore.

The ship was the William H. Sumner, a 165-foot three-masted schooner toting phosphate, mahogany and ironwood from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to her homeport in New York.

Several hours after passing Wrightsville Beach, the Sumner ran aground around 8 p.m. Sunday, Sept. 7, 1919, on a sandbar off Topsail Inlet.

“It accidentally ran aground,” says Nathan Henry, lead conservator with the state’s Underwater Archaeology Branch at Fort Fisher in Kure Beach. “Nobody knows why. It’s a mystery.”

A 28-by 11-foot section of the ship was again exposed on the beach in May 2015 following periods of high surf during Tropical Storm Ana.

Billy Ray Morris, director of the state’s Underwater Archaeology Branch, says archaeologists have known about the wreck for nearly five decades.

“The wreck didn’t actually wash up,” he says. “When storms come along, the sediment washes off.”

Each time the ship’s fragment resurfaces, near Public Beach Access No. 12 in Surf City, in the 700 block of North Topsail Drive, the mysterious circumstances surrounding its demise and the unresolved death of its captain resurface with it.

The Sumner was manned by a crew of eight: Caribbean seamen Leonida Edassarias, Aylando Frank, Aylando Quinonnes and Ramon Gonzales; the steward, Charles Wallace; the second mate, P.J. Antione of Louisiana; the first mate, African American Charles Lacey, and the skipper, Robert E. Cochrane — a 24-year-old from Bath, Maine, leading his first voyage.

Lacey arrived in Hampstead around noon Monday, Sept. 8 and reported the ship ran aground due to strong currents that had steered the vessel toward the shoals of Topsail Inlet. The following day’s issue of the Wilmington Morning Star stated Lacey referenced eight feet of water in the ship’s hold and Capt. Cochrane had a “fit of despondency” and shot himself in the head with a pistol at 6 a.m.

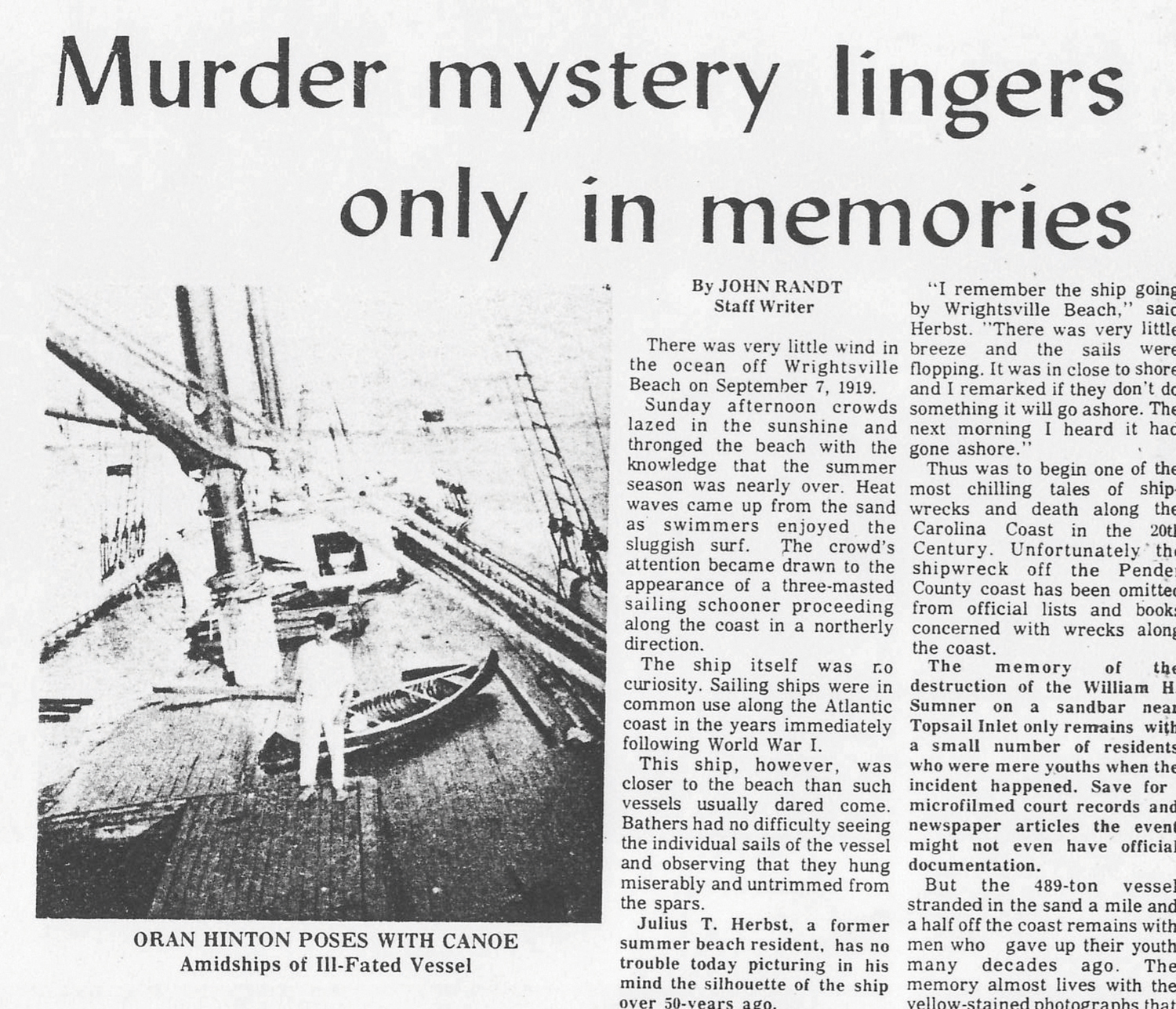

Before the Sumner split in half Sept. 9 at 8 a.m., a group of local boys purchased a canoe and rowed out to the ship as it rested just off Topsail Island. The crew had been taken ashore in Pender County. The boys were rumored to have seen a bullet still lodged in the captain’s cabin. The vessel broke in two soon after, before the tugboat Blanche could salvage it.

Five hours later, Pender County Coroner Will Pearsall removed Cochrane’s body. Pearsall, like many Hampstead locals, was suspicious of the account of Cochrane’s death reported by Lacey. He assembled a six-man jury and began an investigation.

After the jury was “unwilling to accept the theory of suicide as the cause of the skipper’s death,” the case was handed to United States District Attorney H.P. Whitehurst of New Bern.

Left: In a newspaper clipping from 1919, Oran Hinton poses with a canoe on the deck of the ill-fated ship, unaware of the brewing trouble the crew faced onshore. Newspaper article courtesy of the Department of Cultural Resources. Right: A 28-foot by 11-foot piece of the wreck was again uncovered in Surf City in May 2015 after Tropical Storm Ana. WBM File photo

“It is suggested that the course might have been lost and the vessel hopelessly involved in the countless shoals off the Carolina Coast, resulting finally in her going ashore,” The Morning Star reported Sept. 11. “Assuming that this premise is correct, it is believed that the crew, with ship aground and discovery imminent, killed the captain.”

Three crewmembers are reported to have broken down after three days of questioning. Wallace, the steward, said Lacey had a reputation for being violent.

Two other crewmembers spoke, through Spanish-English interpreter Nicolas Morel, of Lacey’s “naturally vicious and trouble-making disposition.”

It was rumored Lacey engaged in “a shooting scratch with a native” in Puerto Rico a few days before setting sail.

However, the other three crewmembers insisted Lacey and the captain were amicable.

Against Whitehurst’s recommendations, all crewmembers were jailed with bonds of $1,000 each and Lacey was scheduled for trial in federal court on Nov. 19.

After deliberating for 26 hours, the jury voted 7-5 in favor of charging Lacey with first-degree murder. Lacey refused to plead guilty, and he and the other crewmembers remained jailed until the following May, when the case returned to court.

During the second trial, prosecutors argued the bullet found in the cabin wall was in direct line with the broken window through which the shot was believed to have been fired.

However, Raleigh attorney Charles U. Harriss argued — on Lacey’s behalf — it was common practice for a captain to choose to go down with his ship. The jury finally rendered a not guilty verdict.

Lacey declared his relief and swore he’d “catch the first thing that smoked for Alabama.”

Other remnants of the Sumner have never been located.

“They could be completely disarticulated miles away,” Morris says.

Note: Unattributed quotes are excerpts from issues of the Wilmington Morning Star published between September 9 and 23, 1919.