The Lifeblood of North Carolina

BY Simon Gonzalez

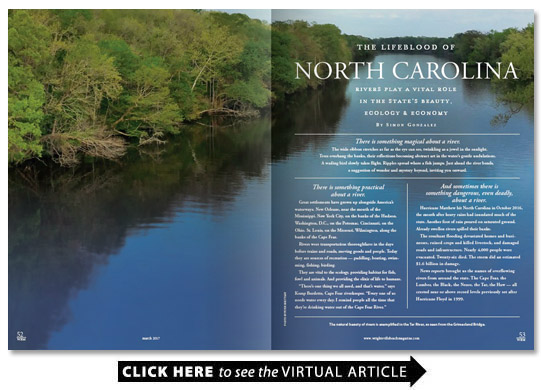

There is something magical about a river.

The wide ribbon stretches as far as the eye can see twinkling as a jewel in the sunlight. Trees overhang the banks their reflections becoming abstract art in the water’s gentle undulations. A wading bird slowly takes flight. Ripples spread where a fish jumps. Just ahead the river bends a suggestion of wonder and mystery beyond inviting you onward.

There is something practical about a river.

Great settlements have grown up alongside America’s waterways. New Orleans near the mouth of the Mississippi. New York City on the banks of the Hudson. Washington D.C. on the Potomac. Cincinnati on the Ohio. St. Louis on the Missouri. Wilmington along the banks of the Cape Fear.

Rivers were transportation thoroughfares in the days before trains and roads moving goods and people. Today they are sources of recreation — paddling boating swimming fishing birding.

They are vital to the ecology providing habitat for fish fowl and animals. And providing the elixir of life to humans.

“There’s one thing we all need and that’s water ” says Kemp Burdette Cape Fear riverkeeper. “Every one of us needs water every day. I remind people all the time that they’re drinking water out of the Cape Fear River.”

And sometimes there is something dangerous even deadly about a river.

Hurricane Matthew hit North Carolina in October 2016 the month after heavy rains had inundated much of the state. Another foot of rain poured on saturated ground. Already swollen rivers spilled their banks.

The resultant flooding devastated homes and businesses ruined crops and killed livestock and damaged roads and infrastructure. Nearly 4 000 people were evacuated. Twenty-six died. The storm did an estimated $1.6 billion in damage.

News reports brought us the names of overflowing rivers from around the state. The Cape Fear the Lumber the Black the Neuse the Tar the Haw — all crested near or above record levels previously set after Hurricane Floyd in 1999.

The Cape Fear River of course is well known in this area. The Riverwalk downtown rivals the beaches as the top tourist attraction. Enormous cargo ships sail upstream after crossing oceans disgorging cargo at the Port of Wilmington. The river is a popular place for boating fishing and walking.

Albeit in negative circumstances Matthew served as a reminder that waterways are the lifeblood of North Carolina.

“Philosophically speaking our natural resources belong to all of us ” says Burdette one of more than a dozen riverkeepers in the state charged with protecting the waters ensuring they are swimmable fishable and drinkable. “Around here and in a lot of places in North Carolina the rivers and our waterways are the foundation of our economy. The more people that are coming here to enjoy the river that come here to fish and get out in boats and walk along that riverfront and stay in hotels the more people that come here because this is a beautiful place the better we all do.”

There are 17 river basins in North Carolina and dozens of named rivers and tributaries. The state contains more than 40 000 miles of rivers and streams which are home to 217 freshwater fish species.

In eastern North Carolina the major rivers include the Cape Fear the Neuse the Tar-Pamlico and the Lumber. Each is important to the ecology and economy of the region.

Cape Fear River

Facts & Figures

The Cape Fear begins at the confluence of the Deep and Haw rivers just north of Greensboro and empties into the Atlantic Ocean 202 miles later. The 35 miles between Wilmington and the ocean is called the Cape Fear Estuary.

Major tributaries include the Black River which connects with the Cape Fear 15 miles above Wilmington and the Northeast Cape Fear River which enters at Wilmington. These are blackwater rivers flowing through swamps and wetlands with decaying vegetation and decomposing leaves that leach tannins into the water. This makes the water tannic — acidic and dark.

The Cape Fear River basin is North Carolina’s largest covering 9 000 square miles. Its rivers and streams touch 29 of the state’s 100 counties encompassing nearly 30 percent of the total population.

History Lesson

The river was called the Sapona by the land’s indigenous people Rio Jordan by Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano and the Charles and Clarendon by early English explorers. The name Cape Fear stuck in the 1700s and is derived from the “Cape of Fear ” the term given to the river mouth by explorers in the late 1500s because of the dangerous offshore shoals.

Wilmington became a leading exporter of naval stores — tar pitch and rosin the products of vast longleaf pine forests. A series of three dams and locks was built to ease the flow of goods upriver to Fayetteville.

The Cape Fear was a major artery for the Confederate Army during the Civil War shut down when the Union won victories at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher and the Battle of Wilmington early in 1865. The river was a means of escape for runaway slaves fleeing via the Underground Railroad.

Recreation

Paddling kayaks canoes and paddleboards are popular pastimes along the Cape Fear and its tributaries.

“It’s a beautiful river ” says Burdette who leads a paddle on the third Saturday of each month beginning in March. “It’s more than just the Cape Fear. There’s the Black and the Northeast Cape Fear. Each of those rivers has some amazing sections.”

It’s also an amazing river for fishing with saltwater species at the mouth and freshwater species further upstream.

“The Cape Fear is a neat river ” Burdette says. “A lot of your really popular saltwater fish live where the river is salty — red drum sea trout flounder lady fish Virginia mullet pompanos. All of those fish you can basically catch from Wilmington down. Then you’ve got your anadromous fish migratory fish like striped bass and shad. You also have all your freshwater species. Catfish. Largemouth bass. Brim crappie bluegill as you go further up. There are places right around Wilmington where you can catch fish that are traditionally salt water fish that are traditionally fresh water and anadromous fish that move in-between. That is kind of fun and unique.”

One of Burdette’s major projects is building passages to make it possible for migratory species to bypass the three dams between Wilmington and Fayetteville.

“Every migratory fish on the river is 5 10 percent of what it once was ” he says. “So now we’re building $12 million $15 million fish passages over these three dams. We’re trying to fix it before we completely lose two species of a sturgeon that are a federally endangered species and two species of shad that were the lifeblood of a lot of these rural communities up and down the river. The spring shad runs were important sources of food important sources of money and of community pride. The annual fish runs have largely gone just barely hanging on.”

Environmental Challenges

Burdette is affiliated with Cape Fear River Watch a member of the Waterkeeper Alliance. The group’s goal is “to hold polluters accountable and protect waterways ” he says.

Cape Fear River Watch and other environmental groups count as victories their efforts to prevent a cement plant along the river in Castle Hayne and to force Duke Energy to close and clean up the coal ash plant in New Hanover County to keep additional pollutants from going into the water.

The current battle is against concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) — hog and poultry farms — further upriver.

“The Cape Fear is kind of ground zero for factory farms ” Burdette says. “They are more highly concentrated in the Cape Fear basin than in any other place on the planet. They concentrate so many animals in such a small area and they produce way more waste than the landscape can absorb. So it ends up running off into waterways.”

The other major issue is storm water pollution the toxic stuff washed into the waterways every time it rains.

“Somebody’s putting fertilizer on their yard so in the springtime it’s nice and green and they are not paying attention to the instructions ” Burdette says. “Somebody is out there letting their dog poop on the side of the road. And somebody is blatantly throwing litter out on the ground. The water is going to pick all of that up mix it up into one big toxic stew and dump it straight into the river. Under the Riverwalk where everybody walks because it’s so beautiful — there’s 100 pipes from every single roadway out here and nobody thinks about those and what’s dumping into the river.”

It’s a tough job and at times tiring. But Burdette won’t give up on his community’s river.

“It is most definitely polluted ” he says. “That river is not swimmable fishable and drinkable all the time and it should be. It’s not at all acceptable to say the Cape Fear is already bad let’s give up on it. I go out on it all the time. I catch fish in that river. Further downstream and further upstream I take my kids swimming in the river. It’s a great river.”

Neuse River

Facts and Figures

The Neuse River begins in Falls Lake Reservoir Dam just east of Durham and runs 248 miles before emptying into the Pamlico Sound making it the longest river contained entirely within the state’s borders.

The Neuse River basin servesnearly one-sixth of the state’spopulation. Major tributaries include Crabtree Swift and Contentnea creeks and the Eno Little and Trent rivers.

The Neuse connects North Carolina’s current capital Raleigh with its first New Bern. It widens and turns brackish at New Bern becoming a sluggish 40-mile-long tidal estuary that empties into the southern end of Pamlico Sound.

It is six miles across at the mouth making the Neuse the widest river in America.

“A cool fact is where the river comes out of the dam in Wake County during the summer months you can walk across it. At the mouth it’s the widest river in the United States ” says Matthew Starr riverkeeper for the upper Neuse.

The Neuse has carved a 100-foot canyon in Lenoir County the centerpiece of Cliffs of the Neuse state park southeast of Goldsboro.

History Lesson

Geologists date the Neuse at 2 million years old making it one of the oldest rivers in America. Archeologists believe indigenous people settled the area thousands of years before Europeans arrived based on prehistoric artifacts found along the banks.

The name is derived from the Neusiok tribe and translates to peace.

TheCSS Neuse an ironclad built by the Confederate navy was sunk in the Neuse during the Battle of Kinston in 1865. The remains of the ship were raised in 1963 and are on display at theCSS Neuse State Historic Site and Governor Caswell Memorial a state historic site.

Recreation

The Cliffs of the Neuse stretch is popular for paddlers and tubers. Fishermen enjoy going after saltwater species toward the river mouth and estuary and freshwater species upstream. Spring migrations on the Neuse produce more catches of shad than any other river in the state.

Environmental Challenges

Large quantities of nutrients mostly from animal waste and fertilizers are the primary threat to water quality in the lower Neuse. Nutrients particularly nitrogen and phosphorous can cause excessive plant growth and algal blooms which remove vital oxygen from the water.

The river crested at record levels near Goldsboro following Hurricane Matthew.

“It was a tremendous amount of water something to see ” Starr says.

The resultant flooding caused a breach of an inactive site at the H.F. Lee Power Plant spilling coal ash into the river.

Sediment pollution is the major issue at the headwaters.

“What we have a lot here in Wake County and Durham County is rapid developments ” Starr says. “If it’s not done responsibly you have sediment pollution. The red clay we have here in the Piedmont it runs off the site and runs into the urban streams which run into the river. The clay particles settle at the bottom and kill the micro-invertebrates which causes issues for bigger stream life.”

Tar-Pamlico River

Facts and Figures

The Tar-Pamlico River basin is the third largest in the state with 2 335 miles of rivers and streams. The 180-mile river begins as the Tar a freshwater stream in the Piedmont near Roxboro. It meets the brackish Pamlico near Washington and continues to the coast to drain into the Pamlico Sound. The Tar officially meets the Pamlico at the bridge under U.S. Highway 17 in Washington.

Some 400 miles of streams connecting to the Tar are designated by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program as nationally significant aquatic habitat. Major tributaries of the Tar include Swift Fishing and Tranters creeks and Cokey Swamp. The Pungo River is the major tributary of the Pamlico.

The river basin includes Lake Mattamuskeet the largest natural lake in the state at more than 18 miles long and six miles wide.

Flooding from Hurricane Matthew caused portions of the Tar to crest at record levels completely inundating historic Princeville the oldest town incorporated by African Americans in the United States.

History lesson

The Pamlico portion of the river was named the Cipo River after the local Native American word for “river ” cites a book of state lore called the”North Carolina Gazetteer.” The first European explorers called it the Pamlico when a surveying group met the Pamlico tribe in 1584.

Sources disagree on the naming of the Tar. Some say it’s from the Native American word “Tau ” meaning “river of health.” Others claim it’s from tar-laden barges that plied the waterway.

Another account says the name comes from Union prisoners who bathed in the river after the Confederates dumped naval stores into the water as theyprepared to evacuate Washington in March 1862. They supposedly stirred up the river bottom so much that the tar smeared their bodies completely.

The river is the site of a sunken Union gunboat theUSS Picket originally used in an expedition along the North Carolina coast led by Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside.

In 2007 low water levels caused by a statewide drought exposed an 80-foot pole boat likely built in the 1820s and used before steamboats when Tarboro and Old Sparta were booming port cities.

Recreation

With little development along its banks the upper section of the river is a haven for wildlife and attracts paddlers fishermen and birdwatchers. There is whitewater paddling in theheadwaters and sea kayaking in the estuary and sound.

Shad and striped bass are popular game fish on the upper part of the river. The Pamlico Sound contains more than 90 percent of all the commercial seafood species caught in North Carolina.

Environmental Challenges

Rivers flowing into the sound face a challenge.

“It’s really a unique system ” says Heather Deck the Tar-Pamlico riverkeeper. “Because of the Outer Banks you don’t have the flushing effect.”

The barrier islands retard the waters from flowing into the ocean so nutrients build up. There’s an ongoing risk of algal bloom and fish kills.

The nutrient pollution largely comes from CAFOs.

“There are half a million hogs in the Tar-Pamlico basin and a growing poultry industry ” Deck says. “A lot of times you see the impact more clearly on smaller creeks and tributaries.”

Increased urbanization is another issue.

“There’s more concrete ” she says. “What used to soak in the ground is now hitting parking lots and draining into the rivers.”

Lumber River

Facts and Figures

The Lumber begins in North Carolina and ends in South Carolina. The headwaters in Hoke County are known as Drowning Creek. The river runs for 115 miles before entering South Carolina. It flows into the Pee Dee River and on into Winyah Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

In September 1998 81 miles of the Lumber were added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system. North Carolina Governor James Hunt sought the designation from Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt.

The Lumber River peaked somewhere around 22 feet 9 feet above flood stage at downtown Lumberton following Hurricane Matthew. About 1 700 people were forced from their homes.

“The poor folks of Lumberton have really struggled ” says Christine Ellis deputy director/river advocate with the Winyah Rivers Foundation. “They were hit hard in the city. Many of them are still in a bad situation because of the flooding.”

History Lesson

Indigenous people settled along the banks long before the first Europeans arrived on the scene. At one site archaeologists uncovered a dugout canoe estimated to be more than 1 000 years old.

Early European settlers called the waterway Drowning Creek because of the dark swiftly moving water. It became the Lumber River in 1809 from the extensive timber harvesting along its banks that were transported down river.

Recreation

The river’s black waters and scenic settings are popular with paddlers fishermen and naturalists.

“People find blackwater rivers fascinating ” Ellis says. “They are beautiful. What I really find is when people from urban areas come to the river you feel like you are in the middle of nowhere. I think that’s what people seek out — getting away getting into nature. Hunting fishing boating those are big uses of the river and the wetlands. Those are uses we consider are worth protecting.”

Environmental Challenges

Ellis is keeping an eye on the Weatherspoon Plant in Lumberton. Duke Energy was scheduled to remove coal ash from the plant in 2019 but it could be pushed back to as late as 2028. Meanwhile major flooding events like the one after Hurricane Matthew put pressure on the earthen berm holding in the ash.

“The problem is that repeated flooding is going to even more severely undermine the integrity of the berm and impoundment ” Ellis says. “We are pushing for a sooner rather than later removal of that coal ash. It’s at risk of failure pretty much at any time.”

Environmentalists are also fighting against the Atlantic Coast Pipeline a proposed project that would carry natural gas from West Virginia. The pipeline would cross the Neuse the Cape Fear and the Lumber near Pembroke.

“For the Lumber River watershed and our extensive wetlands it could have huge impacts ” Ellis says.