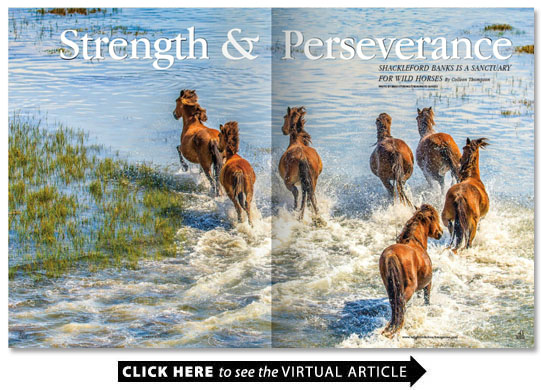

Strength and Perseverance

BY Colleen Thompson

Few visions conjure up the kind of mystery and romanticism that wild horses do. They symbolize unbridled freedom and untamed possibilities. They turn the idealized notion of flawless thoroughbreds on its head embodying perseverance grit and isolation.

They’re engrained in the symbolism and mythology of so many things we love and admire about our country and our state. The very idea that there are still places where wild horses thrive is at its core reassuring and intriguing.

In an increasingly penned-in tamed world the places inhabited by wild horses are the places people don’t live — scraps of landscape yellow deserts and barrier islands ravaged by hurricanes.

Places like Shackleford Banks.

Standing on top of a sand dune overlooking a scrubby island all I could see were more sand dunes and more scrub. There are no houses no campsites no roads. No fences no power lines. The bars on my cellphone all but disappeared.

Shackleford Banks is a slender 9-mile barrier island on the coast of Carteret County North Carolina bordered to the north by the Back Sound and to the south by the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the 56-mile-long Cape Lookout National Seashore and is the southeastern-most region of the National Park Service’s managed sites.

After a 20-minute 3-mile ferry ride from the small town of Beaufort across choppy waters and sea spray with summer temperatures well into the 90s a handful of adventurers landed at the east end of the Shackleford Banks. A kite-boarder overloaded with gear was making the trip because the island provided ideal wind and wave conditions. Others were headed to the pristine uninhabited beach. Along with my husband and me another couple who had sailed from Massachusetts to Beaufort were in search of the wild horses.

Following hoofprints in the sand and dry manure droppings we headed north in the opposite direction of everyone else making our way up and down the dunes and stopping every few feet to pull menacing prickly pear thorns from our shoes.

My husband and wild-horse-search companion using his outdoorsy skill set told me the horses would look for shade in the heat and that we needed to head further inland as I argued that we should look along the beach near the water. “Didn’t you learn anything growing up in Africa? Wild animals always head for shade in the middle of the day ” he said.

The endless dunes the scorching temperature and the suffocating humidity all contributed to the dissent about which direction we should walk in search of the horses.

Clearly our timing and planning could have been better. An early morning start would have avoided the heat. I forgot the bug spray. The drinks in the backpack were already lukewarm. I left my hat on the boat. I definitely wore the wrong shoes. For something I had envisioned and planned for a long time I seemed woefully unprepared.

But I was there for one reason. I had always wanted to see wild horses.

There are about 199 horses on Shackleford Banks. Getting to see them potentially meant trekking for 9 miles crisscrcrossing the island. Then suddenly as we climbed to the top of another dune there they were below us. Just two of them grazing quietly. One bourbon-colored mare the other the color of liquid honey. They raised their heads just slightly but took very little notice of us. The initial irritabilities of the day vanished as we watched them.

I came to chase a dream and tell a story of finding wild horses. I had little knowledge of the tireless fighting and advocacy of the many voices that have helped keep Shackleford intact from congressional legislation and co-management to scientific research and fundraising. All of it combined enables the wild horses to roam free among the dunes.

A Short History of the Banks

For generations people have been telling stories about the wild horses that roam between the dunes on Shackleford Banks. Romantic legend tells us the horses arrived sometime in the 16th century swimming ashore from ships wrecked on Cape Lookout’s hazardous shoals.

We do know that people used barrier islands for grazing lands from the mid- to late-1600s and most ships passing the island carried horses similar to those raised on the mainland. Few historical records exist however and the horses have been there for so long that many generations grew up believing that they were native to the islands.

Edmund Ruffin an agriculture authority who visited the area around 1858 noted that the horses were genetically unique and that outside animals as far as he could tell had not added to the gene pool. Decades of scientific studies confirmed that the horses do indeed have distinctive genetic characteristics shared with Spanish colonial breeds such as the Pryor Mountain Mustang and Paso Fino.

“My mother is from Beaufort and I spent summers there visiting my grandparents. My grandfather Charles Hassell often took me to Shackleford as a child and told me about the wild horses ” says Margaret Poindexter an attorney in Carteret County and president of the Foundation for Shackleford Horses. “We always went over in my grandfather’s boat from Beaufort. There were no ferries to the island back then. My grandfather always said about the horses ‘The island belongs to them.’ I remember one visit in particular I was probably 5 or 6. We had built a fire on the beach to cook hot dogs. We noticed a lone older horse walking down the beach toward us. As he got closer it appeared he was headed straight for what was left of our smoldering cook fire. He was either completely blind or significantly visually impaired. My grandfather got up and spoke to him softly and gently diverted him away from the fire. It made an impression on me that we are only visitors on Shackleford and we have an obligation to be stewards of that place and the horses that call it home.”

Shackleford Banks was originally owned by John Shackleford a Virginia farmer who was granted several tracts of land in North Carolina in 1713 one of which included the thin strip of barrier island. The island became known as “Cart Island ” perhaps a nod to Carteret County where the land resides and remained in the Shackleford family until it was sold in 1805.

By the mid-1800s the island was home to more than 600 people in several communities who called themselves “Ca’e Bankers” (dialect for “Cape Bankers”). The largest town ever established on Shackleford was called Diamond City named after the diamond pattern on the Cape Lookout Lighthouse. The town of about 500 residents was situated on the east end before Barden Inlet divided the island from Core Banks.

A slew of hurricanes hit the island from 1893-1899 convincing most residents to pack up and relocate to the mainland. By 1902 Shackleford was deserted except for livestock and a few roaming horses. In 1933 another storm severed Shackleford permanently from Core Banks at Barden Inlet.

In 1966 Cape Lookout National Seashore was created incorporating all of Core Banks. At one time developers considered building a bridge to Shackleford and turning the island into a tourist destination but in 1986 Shackleford Banks was added to the national seashore and all signs of human existence — cottages fishing shacks livestock — were removed.

Unclaimed equines gained their freedom and Shackleford Banks became a sanctuary for wild horses.

Coming together to Protect and Preserve

There are only two animals the United States Congress has ever specifically passed laws to protect. The first was the bald eagle. The second was the wild horse.

In 1971 more letters poured into Congress over the threat to the nation’s wild horses than any other issue in U.S. history except for the Vietnam War. So Congress unanimously passed the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971.

The act declares that “wild horses are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West; that they contribute to the diversity of the life forms within the Nation and enrich the lives of the American people; and that these horses are fast disappearing from the American scene.”

Even so America’s wild horse population has dwindled from 2 million in the 1800s to less than 25 000 today advocacy group Return to Freedom says.

A retired librarian’s tireless efforts changed legislation to protect the Shackleford horses. Carolyn Mason who grew up visiting the island got involved when the Park Service declared that the horses had multiplied to over 200 and were overgrazing the island and had to be reduced to a herd of 30.

Equine geneticist Gus Cothran of the University of Kentucky warned the Park Service that their number was too small to sustain a genetically viable population. Mason and a group of concerned people from Carteret County stepped up and formed the Shackleford Banks Foundation to advocate for the horses.

In the meantime disease testing on the horses found that they were carriers of an equine infectious anemia. State law requires that any horse carrying the disease must be quarantined for life or destroyed. No quarantine facilities were available for the infected horses and 76 were euthanized.

Determined to protect the future of the herd Mason got the attention of Rep. Walter B. Jones Jr. who introduced legislation in the U.S. House to protect the horses in 1997. Jesse Helms pushed it through the Senate. When a third North Carolinian White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles convinced President Bill Clinton to sign it the Shackleford Banks Protection Act became law.

The horses from then on would be co-managed by the Park Service and the Foundation.

“It’s a 20-year relationship that has grown and thrived to the benefit of the wild horses ” Poindexter says. “There’s always more to accomplish. Nature doesn’t sit still so we need to continue to be vigilant in our educational efforts in monitoring the health and genetic diversity of the herd and continuing to adaptively manage the horses.”

Dr. Sue Stuska joined the National Park Service as an equine biologist in 1996 and has spent the last 20-plus years studying and monitoring the horses.

“We have 119 horses on Shackleford now ” she says. “We are unusual in that we have a legislated population range of 120-130. We make decisions based on horse relatedness within the herd and use birth control as needed. For example females in less well-represented lines don’t get birth control or only get enough to give them a break between foals. Birth control is delivered by a dart so the mares are not sedated or handled for it. What we don’t do are roundups vaccinations feed water medicate or even get close to the horses.”

Keeping the Wild Wild

The wild mustangs of Shackleford Banks continue to be of great interest to the scientific community. Princeton University’s Daniel Rubenstein and his graduate students have been studying and documenting the social behavior of the horses for two decades.

“Colonial Spanish Mustangs are a threatened equine breed and this herd represents one of the few in the wild in the East ” Poindexter says. “The inheritable traits in these horses that have enabled their survival in such harsh conditions may also be of benefit in other equine breeds.”

Rubenstein and his students have developed a system for naming the horses that dictates that the foal’s name start with the first letter of its mother’s name essentially to facilitate their daily observations.

“The students named the horses based on the first letter of the name of their dam. So a mare with a name that started with a T would have offspring with T names as well ” Poindexter says.

Not everyone is a fan of the names though.

“Naming is something people do for pets and these are decidedly not pets ” Stuska says. “I do not call them by name to the public anymore. We have had too many people try to get way too close and there are other ways to identify them. Their allure for me is their natural wild behaviors which can be seen by watching from a distance. We always endeavor not to change their behaviors by our position or actions.”

Moving on from watching the two mares we continued walking further inland over the dunes and through the high sea oats that have made up the landscape for hundreds of years. As wind and waves move sand around these grasses trap and hold the sand allowing the dunes to build protecting plant life and fragile ecosystems from the damaging effects of salt spray. If these plants were removed the dunes would quickly blow away leaving a flattened more vulnerable island in their place.

Despite the harsh conditions wildflowers of marsh pinks orange and red firewheels and purple needlegrass add splashes of color to an otherwise sun-bleached landscape. Deeper into the island we came across a forest of cedar wax myrtle and live oaks dripping in Spanish moss and tangled vines.

The forest looks completely out of place in what is otherwise a barren environment. The island was once almost completely covered with maritime forest but wave erosion sand and countless hurricanes have all contributed to their demise. On the ocean side of the groves there’s a beautiful haunting display of a “ghost forest.” Trees killed by advancing dunes and salt spray have left sun-bleached skeletons protruding from the sand.

We came across a large fresh-water pond and a gathering of about 10 horses — sorrel liver chestnut bay and black. Some stood in the cool of the water others grazed on the banks. They were smaller and stouter than I expected standing between 12 and 14 hands with thick hooves and shaggy manes. A pale gold foal stuck close to its mother keeping her glare transfixed on our movements.

We decided to sit quietly and just watch. This was what I had pictured all along.

“I find their wild behaviors the source of endless fascination and learning ” Stuska says. “Having known some of these horses for more than 20 years I have watched them grow and develop. It is very important that they take no more notice of me than of some other object on their island. I do not want them to change their behaviors because of my presence as I watch them.”

Driving back home past vacation homes and trailer parks strip malls and countless Bojangles thoughts and images of wild horses sandy dunes maritime forests and salt marshes ran through my head.

I asked Poindexter if she thought a story like this might bring unwanted attention to the horses. Is there a fine line between preservation and promotion and turning places like Shackleford Banks into tourist destinations?

“These horses are an intrinsic part of what is special about this place as much as the lighthouse and fishing and the beaches ” she says. “It’s important to preserve these living legacies. I think a lot of things are drawing people to the island and it’s been that way for many years. We try to turn the challenge of increased visitation into an opportunity. It’s an opportunity to educate more people about what makes these horses unique and what everyone can do to help preserve and protect them.”

Shackleford Banks part of the Cape Lookout National Seashore is just one of many ecologically significant locations along the coast. They include six sites near Wrightsville Beach that are part of the N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve system.

1 Rachel Carson Reserve

The Rachel Carson Reserve is located between the mouths of the Newport and North Rivers and directly across Taylor’s Creek from the historic town of Beaufort in Carteret County. The mix of fresh and salt water creates a pristine estuarine environment where juvenile fish and invertebrates find shelter and food. Horses brought to the site by a local citizen in the 1940s eventually became wild and are considered non-native inhabitants of the islands. To maintain the health of both the horses and the island ecosystem select female horses are given birth control through a remote injection once per year. The horses subsist primarily on saltmarsh cordgrass and they dig for fresh water.

2 Permuda Island

Permuda Island is a small narrow island located in the extreme southwestern portion of Onslow County. Archaeological evidence indicates the earliest occupation occurred as early as 300 B.C. The central portion of the island contains former agriculture fields. Fish shrimp crabs clams and oysters utilize the Stump Sound estuary as a nursery ground. Shorebirds frequent local marshes and mudflats. River otters are occasionally found in marsh and sound areas.

3 Masonboro Island Reserve

Masonboro Island is the largest undisturbed barrier island along the southern part of the North Carolina coast. Eighty-seven percent of the 8.4-mile-long island is covered with marsh and tidal flats. The remaining portions are composed of beach uplands and dredge material islands. Loggerhead and green sea turtles nest on the beaches where seabeach amaranth plants grow on the foredunes. The nutrient rich waters of Masonboro Sound are an important nursery area for spot mullet summer flounder pompano menhaden and bluefish.

4 Zeke’s Island Reserve

Zeke’s Island Reserve is located 22 miles south of Wilmington. The lagoon-like complex is one of the most unusual areas of the North Carolina coast. Both the Atlantic loggerhead and green sea turtles federally protected threatened species occasionally nest on the site’s open beaches. The expanse of intertidal flats in the vicinity is the single most important shorebird habitat in southeastern North Carolina.

5 Bald Head Woods Reserve

The 191-acre Bald Head Woods is part of the Smith Island Complex located just east of the Cape Fear River. It features extremely old large trees in this maritime forest. Live oak and laurel oak are the major species comprising a canopy that shelters the plants from salt spray. The lack of light favors shade-tolerant plants like ebony spleenwort. Cars are not allowed on the island but bicycles and golf carts may be rented.

6 Bird Island Reserve

Bird Island is an undeveloped barrier island located at the southwestern edge of the North Carolina coast situated between Sunset Beach and the Little River Inlet in South Carolina. The Reserve site represents excellent examples of barrier communities with several occurrences of rare species. The most notable are nesting loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) and seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus) a plant of the foredune area. Both species are listed as threatened by the federal and state governments.

Descriptions are excerpted from the North Carolina Coastal Reserve website