Shrimp Tales

BY Simon Gonzalez

It’s the middle of June and Buddy Davis’ trawler is tied up at the family’s fish house on the banks of the New River in Sneads Ferry.

There’s plenty to do around the dock — boats to paint nets and equipment to repair or replace general maintenance to make sure everything is operating like it’s supposed to when it’s time to go out. Davis is 77 but he still does much of the work himself.

“From daylight to dusk he’s finding something to do ” says Stevie Davis one of Buddy’s three shrimping sons.

But it’s not where he wants to be. At this time last year — and the year before that and the year before that — he was out shrimping. But in the early summer of 2018 it’s not worth leaving the dock.

“We hadn’t done nothing here ” he says. “It’s been 6 months since we even caught any shrimp.”

An unusually cold winter is the culprit.

“The shrimp can’t stand real cold water and we had below-freezing temperatures here for over a week around December I think it was ” he says. “Them big white shrimp they just move south.”

Davis has been shrimping “since I was big enough to walk.”

“I’ve been going ever since I was 7 or 8 years old I’d imagine ” he says. “Daddy used to shrimp and I’d go with him.”

He’s itching to get back on the water but when you’ve been shrimping as long as he has you learn to take a philosophical view.

“Some years are good some years are not so good ” he says. “But you’ve got to have a little bad with the good to appreciate it. You can’t have good all the time.”

That’s the life of a shrimper. Some years the nets are filled with the little critters. Others they prove hard to get.

“There’s no guarantee ” says John Norris who has shrimped for about 60 years. “I had a guy come to me one time looking for a job. I said ‘Yeah I can use you.’ He said ‘Can you guarantee me $250 a week?’ I said ‘Bud I can’t even guarantee you’ll get back.’ He didn’t want no job after that.”

No shrimp of course means no money. The key to surviving the lean times is to take advantage of the good times.

“You’ve got to be prepared for the bad times when you’re a fisherman ” Davis says. “You can’t make money one day and spend it the next. You’ve got to save a little bit for bad times.”

It helps that the last few years have been very good.

“We were fortunate. We had three of the best years there’s ever been ” says Liston Norris John’s son. “I’ve not been at it as long as him but it’s unheard of. Just shrimping year-round. The amount of shrimp we caught has been unheard of.”

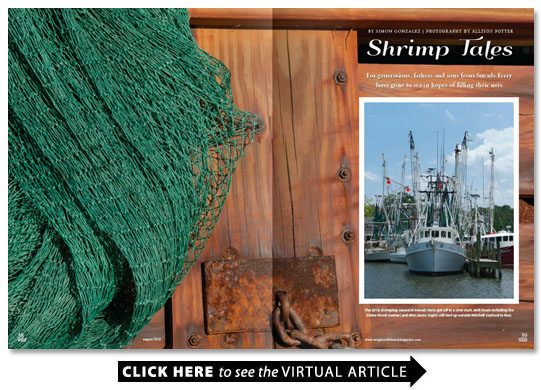

But early this season instead of being out on the water the boats remained tied up along the New River up into Wheelers Creek and around Poverty Point. That’s where the fish houses are located: Davis Seafood Mitchell Seafood and B.F. Millis & Sons.

This is where the weather-beaten men hang out men who have done this all their lives who depend on the annual harvest who are always thinking and talking about shrimping.

Men like Jeremy Edens who shrimps with his grandpa and is kin to the Millises. He hasn’t been out this year either but still has hopes for a good season.

“My brother shrimps ” he says. “He talked with someone who does the tests in the Pamlico Sound and said it looks better than last year. If that’s the case we’ll be OK. Last year the Pamlico Sound was really good.”

This is life in Sneads Ferry a town of 9 750 some 37 miles north of Wrightsville Beach just below the Marine base.

The ferry in the Onslow County town’s name dates back to 1728 when Edmund Ennett began taking passengers across the New River. The Snead is Robert Snead an attorney who settled here in 1791.

The community soon became established as a rural fishing village. Just about everyone made their living from the water.

“That’s all we know to do ” Buddy Davis says. “That’s all my daddy done and his daddy. I don’t know how far back it goes.”

These days not many people are involved in shrimping and fishing. The population has grown 80 percent since 2000 mostly because of the proximity to Camp Lejeune. Sneads Ferry is no longer a little shrimping village.

“A lot of people call it that but it really ain’t that no more. Not to me ” says Warren Hostetler Buddy Davis’ nephew and a shrimper for about three decades. “That’s what it mostly was when I was growing up. Fishing or shrimping. Trust me it ain’t like it used to be. It’s changed so much. You’ve got more people and more business. You’ve got the Marines. You’ve got people that work on base. A little bit of everything.”

At one time there were at least seven fish houses and a lot of boats supplying them with shrimp. Now there’s the three on the New River with the shrimp boats tied up outside and Grant’s Oyster House up Mill Creek and a handful of boats.

“There used to be a lot of boats come out here ” Hostetler says. “It used to be 16 17 boats at a time. We’d work right along the beach here. But it got so sorry people started getting out of it.”

Times have changed. High fuel prices and what the shrimpers see as often draconian regulations have altered the town and the industry.

“One of the biggest things that’s changed is it used to be I could take flounder nets with me ” John Norris says. “You can’t do both now. You’ve got to get a permit to do anything anymore. If I go rock shrimping I’ve got to have a rock shrimp permit. If I go floundering I’ve got to have a flounder permit. What they’re doing is making it so you can only do one thing.”

Other proposed or rumored regulations have the shrimpers worried. Liston Norris says they want to keep the boats at least three miles from shore because the bycatch is bringing sharks too close to the beach.

“Every little thing that is bad in the water gets blamed on us ” he says. “We get a bum rap. They act like we’re just out there to do harm. I don’t know a fisherman that’s out to do harm.”

Buddy Davis has heard about restrictions in one of the most fertile spots.

“They’re trying to close Pamlico Sound now ” he says. “They want to put regulations on it three days a week. People can’t work three days a week. I think there’ll be shrimp right on and on and on but you never know about the laws they’re going to pass.”

Still shrimping remains in the DNA. The town sign proudly proclaims Sneads Ferry as the “Home of the Shrimp Festival.” The annual event held the second weekend in August since 1970 celebrates the community’s heritage with a parade a Shrimp Ball a pageant and a fair on the festival grounds featuring naturally lots of shrimp to eat.

Shrimping is also in the DNA of those who still go out. It’s a family affair in Sneads Ferry a vocation passed down from generation to generation.

Hostetler begins ticking off the shrimping families.

“The Millises — my grandma her mother was a Millis; we’re related to them. The Davises. The Folgers and the Edens. The Mitchells ” he says. “Somewhere down the line we’re all related.”

Stevie Davis is one of Buddy Davis’ three sons. He and Billy are shrimpers. Jody runs the fish house with his wife Vikki.

“I was on a boat when I was 13 ” Stevie says. “I’m 55 now.”

The fish house started out as a small bait and tackle store built by Buddy’s parents Theron and Laura Lee in the 1940s.

“My grandfather used to rent out little skiffs so people could paddle out and fish ” Stevie says. “He sold bait and stuff here. My grandmother she would make lunches and drinks to sell. When my dad got old enough he built this fish house.”

Kim Mitchell married into the shrimping business. She helps run Mitchell Seafood for her father-in-law and goes out on the boats when extra crew is needed.

“This is life here ” she says. “My father-in-law it started with his mom and dad opening a tackle shop. He’s been around it his whole life. A lot of them have grown up with each other. There’s a lot of families.”

There are no family feuds here. Cooperation not competition characterizes shrimping in Sneads Ferry.

“We kind of work together ” Mitchell says. “The boats converse when they’re out there. We try to help each other out. Everything is good.”

Boats are named after wives and children and passed down from father to son. Buddy Davis built the William Michael a 60-foot wooden trawler in 1968 and named it after his two oldest sons. The Barbara Joe Stevie’s boat is named after two of Buddy’s children.

Liston Norris runs the Linda Ann handed down from his father John.

“The original builder it was named after his wife and my dad’s partner’s wife ” he says. “That’s the only name that boat has had since it was built. I always tried to get him to change the name. It’s bad luck to change the name of a boat he says. So it’s always been named that. I grew up on that boat since I was 5 years old.”

John Norris is one of the few first-generation shrimpers in Sneads Ferry.

“We moved from Pender County. I was born up there ” he says. “We lived on farms until I was 13 years old. I’ve cropped tobacco plowed with a mule. We moved to Sneads Ferry in August of 1957. I told my parents I’m through with farming. No more. Never.”

He learned shrimping by picking up jobs on boats in the summer. He was working in the warehouse for a paper company when he got married in ’66 but quit to run his own boat.

“I told my wife I don’t ever intend to do anything else but fish ” he says. “We won’t starve. I never went back to that job.”

It seemed that Liston was destined to be a shrimper; when he was born John paid the delivery doctor with 100 pounds of shrimp. But the father wasn’t sure he wanted his son to spend his life on the boat.

“He told me he didn’t want me to be a fisherman the whole time growing up until I decided to do it ” Liston says. “Then he told me there would be tough times but if you’ve got the want for it you’ll be OK. I can’t imagine doing anything else. This is all I’ve ever done. I feel like it’s the greatest job in the world.”

That’s a common refrain. There are tough times like this year when there weren’t enough shrimp to take the boats out before July. Maintenance and fuel are expensive. Regulations and competition for cheaper imported farm-raised shrimp make for an uncertain future.

There are also literal obstacles. Sneads Ferry shrimpers can only get through the New River Inlet at the highest of tides.

“Last year we’d come and go on high water and I’d hit most times ” Stevie Davis says. “It’s about as wide as the boat is. There ain’t no room for error. At nighttime it’s nerve-wracking. At low water we have to go to Morehead or go to Wrightsville to go out four hours each way.”

There are long hours and days away from home and family.

“It’s about a 10-hour run up to the Sound ” Buddy Davis says. “Then we work three or four days before we run them back home.”

But when they are trawling on the water with their nets extended and filling with shrimp it’s the greatest job in the world.

“It’s in my blood ” Hostetler says. “When it’s peaceful when it’s going good and you’re catching a few shrimp it’s great. You couldn’t ask for no better.”

That’s what keeps Buddy Davis going out year after year. He might be 77 but he has no plans to retire.

“I just want to go I’ve just got to go ” he says. “It’s peaceful out there. It sure is. It ain’t like being out there on that highway. You just feel free. I’m my own boss. I don’t have to listen to anybody. I do what I please.”