Selling Nostalgia

Wrightsville Beach residents fondly remember Newell’s

BY Michelle Bliss

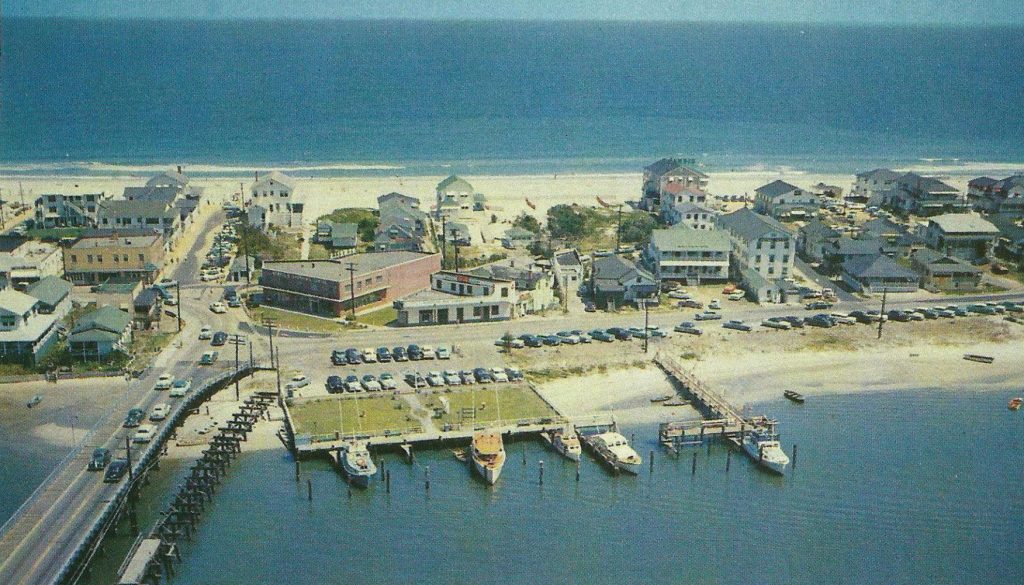

Newell’s began as a popular open-air concession stand at Station One on the trolley car line owned by the Tidewater Power Company. Back in the 1920s, visitors paid 25 cents to ride into town on a beach car. The concession stand was their first stop.

Originally owned by Bud Werkheiser, the wooden stand included a soda fountain that served Coca-Cola along with milkshakes and malts. Customers could also order a sandwich and read the Wilmington or Raleigh newspapers.

The concession stand narrowly escaped the Great Fire of 1934. Lester Newell and his wife, Mickey, bought the stand that same year after running it for a number of years.

The stand had a countertop, tables and chairs, and fold-up sides in case it rained. Eventually, permanent walls were added so the stand could remain open in the winter months. Lester and Mickey also put up a “Newell’s Soda Shop” sign, as well as advertisements for Budweiser and Buttercup Ice Cream.

The late Bill Creasy Jr., Wrightsville Beach’s unofficial historian, frequented the concession stand in the late 1930s and ’40s as a young boy and teenager. He remembered walking to the stand with his friends and trying to decide between a Baby Ruth and a comic book. Back then, fountain drinks and candy bars cost a nickel, and a milkshake was just 15 cents.

Creasy explained that while Lumina Pavilion was the hangout for kids on the southern end of the beach, Newell’s was the place to be in the middle of town.

“We all hung out there and grew up there,” he said in 2009.

Times were different then. Parents felt at ease letting their children gallivant freely around town with friends. And there was something wholesome about a family-owned business like Newell’s.

Linda Brown, a Wrightsville Beach resident who lived on the beach for five years as a child and came back in the summers as a teenager when her grandmother, Levi Murdoch Braswell, bought a house on Crane Street in l962, feels the same way.

“When you were a teenager and you were loose on a Saturday, you always went to Newell’s,” she says.

By the time Brown was visiting Newell’s in the early 1950s, it had moved into a brick building with more space and variety. No longer just a concession stand, Newell’s boasted an array of women’s clothing and beach supplies in addition to the soda fountain.

The Newells kept adding more space, holding a grand opening of the renovations on May 28, 1955, advertised in a “Special Newell’s Edition” of the Wrightsville Beach Newsette. That weekend, customers could buy men’s handkerchiefs for 7 cents, bobby pins for a quarter, and three “soft, thirsty 20 x 40 Cannon towels” for a dollar. The store also carried Coty 24-hour lipstick and Lady Manhattan tailored shirts, along with an array of hardware items and fishing gear.

Brown recalls how it felt to see the store on her family’s way into town for summer vacations.

“It was like the Welcome to Wrightsville Beach sign,” she says. “We couldn’t wait to see the Newell’s sign.”

Brown lived in Raleigh as a teenager, but always waited to get her bathing suits at Newell’s, including a green-and-white polka dot two-piece her mother bought her. She also fondly remembers the beautiful displays of shoes, jewelry and sunglasses.

Even as a child, she understood that Newell’s was a special treat.

“When you went in there you knew you needed to behave yourself,” she says. “It wasn’t like going into Woolworth’s and going crazy. That’s the way it was. It was respect.”

Along with buying clothing and presents for her friends back home, Brown liked spending time at the soda fountain, where they always knew her order.

“What I loved the most was getting up at the soda bar and just hearing old-timers in there,” Brown says. “You knew that they were the old Wrightsville Beach or Wilmington people. And just hearing them talk and tell stories was fascinating. The saddest day was when they took it down, when it went away as Newell’s.”

Around the same time, Wrightsville Beach residents Elizabeth King and her brother, Michael Brown, were also sitting on the bar stools at the soda fountain. They grew up on the beach, visiting Newell’s in the 1950s and ’60s. They remember ordering Cokes with squirts of vanilla or cherry syrup to wash down their grilled pimento cheese or chicken salad sandwiches.

As full-time residents of the beach, King and her brother recall desolate winters when the tourists had all left and the summertime buzz had faded away and Newell’s was one of the only places open.

They both enjoyed leafing through the comic books. King would read “Archie” and her brother was crazy about “MAD Magazine.” Brown says Lester Newell’s mother used to keep an eye on the children from the second-floor landing, making sure they weren’t horsing around or spending too much time in the comic books section.

In addition to riding to Newell’s on their bikes by themselves, King and Brown remember why Sunday nights at the store were so special.

“Every Sunday, we had a big lunch in the middle of the day,” King explains. “Well, by the end of the day, my mother wasn’t going to cook twice, so my father would take my brother and me up to Newell’s, and we got to pick our own pint of ice cream to eat, all by ourselves.”

Brown says this Newell’s ritual has become a bit of family lore.

Both King and Brown remember when the Newells sold the store in 1969 to John C. Drewry.

By that time, Newell’s was open 364 days a year from 7 in the morning until 10 at night in the summertime. The Newells continued working at the store for a year to help Drewry learn the tricks of the trade. They accompanied him to clothing shows and taught him how to order merchandise and manage a staff of 15 employees.

In 2009, Drewry described Lester Newell as “a good friend as well as a business associate. He tried to teach me all the secrets he knew, just like you would to a son.”

Drewry marveled at his mentor’s success as an entrepreneur. Lester Newell envisioned a hub of activity around his store so that shoppers could park in one lot and visit the post office, the bank, the ABC store and the department store all in one trip.

When they entered Newell’s, customer service was a priority.

“When you went in that store, someone was Johnny Quick to see if they could help you find something,” Drewry said. “It’s not like today when you see two salespeople sitting there, one chewing gum and talking and standing on the shovel with their foot propped up saying, ‘One of these days I’m going to own this company.’”

Mickey Newell was also a talented merchandiser. Drewry said she had a clientele of a few hundred people she shopped for at clothing shows.

Before the Drewry family sold the store to Cecil and Margaret Seal in 1976, they added a missy clothing line for teenage girls inspired by their daughter, Catherine. They also continued serving free coffee, just as the Newells did, so that a group of about 15 men, mostly boat captains and retirees, could meet for an informal coffee club.

Drewry would visit with the club each morning to talk about fishing, boating and local politics. By this point, the soda fountain had been replaced by vending machines for coffee and Stewart Sandwiches.

Despite their dedication to the store, the Drewrys had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy when the Seals bought it. The store was still operating but reorganization was needed.

“Cecil Seal had a long history of mercantile training,” Drewry explained. “He had worked for Roses for years and years.”

That, Drewry said, was exactly the experience needed to recover the store.

The Seals continued operating the store until 1992 when they sold it to Wings, the beachwear chain based in Myrtle Beach. In its final year, Newell’s made more than $1 million in sales and employed 20 people during the tourist season.

Madeline Flagler, executive director of the Wrightsville Beach Museum of History, vacationed in Wrightsville Beach as a girl and fondly remembers going to Newell’s in her bathing suit and shorts to buy T-shirts and penny candy, like Mary Janes and bubblegum.

“Newell’s was a real local place that you felt was really connected to the community, and Wings was another chain,” Flagler says. “Those kinds of family and community-oriented businesses are vital to the story of any community.”

Linda Brown misses Newell’s as well, because she wants her nieces and other children to have those memories.

“And sometimes I wonder what it would be like if it were still there,” she says. “How would it have handled all of the changes?”

Even though those who hold fond memories of Newell’s wish it were still a part of the landscape at Wrightsville Beach, it will always remain a symbol of an era gone by, a story to be shared from one generation to the next.

First published December 2009. Sources: The Bill Creasy Collection, The Bill Reaves Collection at the New Hanover County Public Library, Tide and Time: A History of Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina (Commissioned by Wrightsville Beach History Museum and written by Virginia Whiting Kuhn), Wilmington: Lost But Not Forgotten (by Beverly Tetterton.)

Mr. Knowledge

Remembering Wrightsville Beach’s fount of local lore

The late Bill Creasy Jr. was for decades the local go-to guy for Wrightsville Beach lore, history and preservation efforts.

Creasey served as vice president of the four-person Wrightsville Beach Preservation Society, founded by Greg Watkins, who had restored the 1910 Tarheelia Inn on North Lumina and later wrote Wrightsville Beach: A Pictorial History.

“My grandparents moved to Wrightsville Beach in 1915 and lived on Columbia Street right down here,” Creasy said in a 1990s interview for Wrightsville Beach Magazine with Gretchen Nash from his home overlooking Banks Channel. “My dad bought a house on Charlotte Street in 1926. I was born in 1928 and that was about my first summer down here. It was a little cottage that was not winterized or anything.”

As many families did back then, they were Wilmington residents who moved down to their cottages on Memorial Day and moved back on Labor Day.

Boxes of old photographs depicting life at the beach in the early 1900s were passed down to Creasy from his father. In 1992, Watkins and Creasy enlarged the old black-and-white photos for display on the west side of Newell’s Department Store, and then again at Wynn Plaza where the town docks are.

Creasy commented this was probably the first time that newcomers and tourists got a glimpse of life on the beach before automobiles and paved roads.