See You Now Alligator

There are gators in our midst

BY Simon Gonzalez

It’s a beautiful, sunny Friday in April. The day dawned on the chilly side, but it’s quickly warming up. It is going to be a perfect, pleasant early spring day in coastal Carolina.

In normal circumstances, the Swamp Park in Ocean Isle Beach would be teeming with school children on field trips and tourists enjoying the adventure park and swamp boat tour. But these days are far from normal. The statewide stay-at-home order because of COVID-19 is in effect. The park is closed indefinitely.

Only people with essential jobs are supposed to be reporting to work. That includes George Howard, the general manager of the Brunswick County attraction.

The park might be closed, but the gators still must be fed.

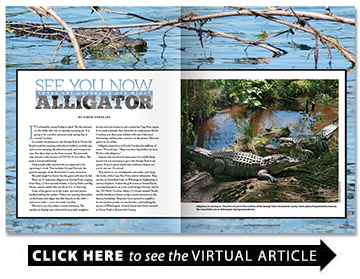

There are 15 American alligators at Swamp Park, ranging from Max, a 3-foot juvenile female, to Leroy, Nubs and Big Mama, mature adults who are about 9 to 11-feet long.

Some of the gators are in the water, eyes and snouts barely breaking the surface. Others are sunning themselves on the banks and ridges. Just like they do in the wild — and not so wild — areas of coastal Carolina.

This isn’t a zoo, but rather a rescue sanctuary. The reptiles on display were relocated from ponds, neighborhoods and even homes in and around the Cape Fear region. It is a stark reminder that if you live in southeastern North Carolina, you share your habitat with one of the most fascinating and fearsome creatures on the planet. There are gators in our midst.

“Alligators have been in North Carolina for millions of years,” Howard says. “They were here long before we were. We live with alligators.”

Anyone who has lived in these parts for a while likely knows it is not necessary to go to the Swamp Park to see gators. If you’ve spent much time outdoors, chances are you’ve see one. Or several.

They thrive in our swamplands and creeks, and along the banks of the Cape Fear River and its tributaries. They are also in Greenfield Lake in Wilmington, frightening to unwary kayakers. And at the golf course at Sunset Beach, sunning themselves on a rise overlooking a fairway. And at the USS North Carolina, where a 13-footer named Charlie and his family are almost as big a tourist attraction as the famous battleship. They have been spotted in neighborhood retention ponds, on area beaches, and walking the streets of Wilmington. Several dozen have been counted at Orton Pond in Brunswick County.

“This is the northern range of their territory,” says Alicia Davis, a biologist with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. “They are here.”

Davis, who has been with the NCWRC since 2015, became the agency’s American alligator biologist in Oct. 2017. It was a new position, added because of a rise in the alligator population in the state. Or, at least, an uptick in the number of gator reports.

“We’ve had an increase in the number of calls from the public with concerns about alligators,” she says. “It’s not a surprise if you think about an increase in human population on the coast. More people come in contact with gators. There’s less and less quote ‘wild places.’ Alligators don’t mind at all living in retention ponds or in a pond on the golf course.”

The calls typically go something like this: “Oh-my-gosh-I-just-saw-an-alligator-in-my-neighborhood-I’m-so-scared-it’s-going-to-eat-me-do-something!”

“People call shocked, what do I do? ‘I have children and pets,’” Davis says. “Lots of times it’s a tourist or someone who just moved to the area. I hear it all the time; I didn’t even know alligators were here.”

The calls increase this time of year. Alligators are cold-blooded creatures. During the winter they go into a state of dormancy called brumation. Their metabolism slows and they become lethargic. They are most active when the weather warms up. The wildlife commission receives hundreds of calls during the hottest four or five months of the year.

The concern about gators is understandable. They are fearsome looking. Intimidating. Scary. The scales, the armor, the spiky tail, the teeth. The half grin, as though it’s contemplating some inner-species joke about how the vulnerable, defenseless human just thinks it’s at the top of the food chain.

We’ve all seen the nature shows where the unsuspecting antelope goes to the waterhole for a drink only to be grabbed by the huge prehistoric lizard with the big jaws and teeth.

“You see an alligator, and it scares the crap out of you,” Howard says.

But if you live in the Wilmington area and have a close encounter of the gator kind, fear not.

“Historically alligators are looking for rodents usually first, birds second, and then opportunistic,” Howard says. “That may be fish, snakes, lizards, frogs, anything it can get its hands on. The only time that they’re going to mess with you is if you’re getting in their way of doing something.”

The key to coexisting with alligators is to, as Howard puts it, “let wild be wild.” Don’t live in fear of them, but recognize that they are an untamed, potentially dangerous creature and give them a wide berth.

“They’re actually pretty shy creatures,” Davis says. “A naturally behaving alligator, if they see you their instinct is to avoid you. They’ll go in the water and submerge. There’s only five instances that we have documented of people that have been bitten by an alligator. None were fatal, and all were provoked by the person. If you don’t want to get bit by an alligator, don’t jump on it.”

Humans and alligators typically co-exist just fine as long as that basic protocol is followed. But if it is violated, the relationship is out of balance.

“What can change that is if people feed alligators,” Davis says. “Just like any wild species, if a person feeds an alligator it will teach an alligator to associate people with food.”

It’s a potentially dangerous scenario when a gator sees a human as a possible food source. In that case, alligators can be a danger and must be relocated.

“A local biologist will do a site visit,” Davis says. “It would be up to that biologist to make a determination if that alligator needs to be relocated. Most of the time it is relocated for the alligator’s safety. It’s people misbehaving and not the alligator.”

About four or five are moved a month during the summer. Often, they are taken back to the wild. The Holly Shelter Game Land in Pender County often is a gator’s new home. Sometimes it’s the Green Swamp in Brunswick County.

Sometimes, the determination is made that there has been too much interaction with humans, or the gator would be unlikely to survive in the wild.

“Two to three times a year here lately an alligator will turn up well out of alligator range, in the Piedmont or foothills,” Davis says. “A person assisted it in getting there. We have to assume that animal was in captivity for some time. Maybe someone got it as a pet and released it, which is illegal. It could have a disease, or been fed by people all its life. We don’t want to release it into wild areas. We try to take them to captivity when we can.”

That is where an alligator rescue facility like the Swamp Park comes in.

“The only time we are able to accept an alligator is if N.C. Wildlife determines it is a nuisance in such a manner that it is no longer allowed back into the wild, or if the alligator was previously in captivity,” Howard says.

The Brunswick County facility was licensed by the state and began receiving alligators in 2016. The primary purpose is to be an education resource, to tell the school groups and the public about the gators in our midst, and how we can co-exist.

“You’d be amazed how many folks don’t know anything about the American alligator,” Howard says. “That intimidates people. Learn about them. Educate yourself about them. All of a sudden you gain an interesting relationship because you become excited about them. Alligators are a very important part of the ecosystem of eastern North Carolina, and they deserve our respect just like any other animal would.”

With a little education, alligators transform from something to fear to something to appreciate.

“Enjoy them,” Davis says. “But enjoy them from a safe distance. Give them the respect they deserve and let them be wild.”

American Alligator

Alligator mississippiensis

Classification Class: Reptilia | Order: Crocodilia

Many different kinds of alligators existed in the prehistoric past, but only two remain today: the Chinese alligator, which inhabits the lower Yangtze River valley in China, and the American alligator.

Description

Adults range in color from black or dark gray to dark olive. Alligators have a broad snout that is useful for digging, a short neck and legs, and a thick tail that is used to propel them through water. Contrary to popular belief, the tail is not used to attack prey. Two turret-like eyes stick above the skull so the alligator can see above the water as it swims. Its leathery skin is toughest on its back, where small bones called osteoderms create a rough, ridged shield. Unlike the turtle, these hard, flat bones are not connected to each other, so the alligator retains greater flexibility.

History and Status

The American alligator became scarce in the early 20th century due to loss of habitat as well as unregulated hunting for hides and meat. In 1967, it was one of the first species the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed as Endangered. This protection allowed alligator populations to recover in many areas. Today, it is federally listed throughout its current range as Threatened

Breeding/Young

Takes place in May and June. One brood per year. Females may not breed each year. Average clutch size is 30-45 eggs. Hatchlings are protected by the mother for up to two years.

Life Expectancy

American alligators can live 40+ years in the wild and 65+ years in captivity.

Food

Young alligators eat insects, frogs, small fish and crustaceans. Adults eat fish, snakes, frogs, turtles, birds and mammals such as muskrats. They feed primarily at dawn and dusk.

Average Size for Adults

Females generally grow to less than 9 feet while males can grow to 12-13 feet and weigh 500 pounds or more.

Human Interaction

Alligators rarely attack humans, and the attacks that do occur are most often caused by people who deliberately provoke or harass them. However, a close encounter with an alligator can be dangerous. Females actively defend their nest and young, and care should be taken when in or around areas where alligators are found. Alligator hunting is allowed by permit only in North Carolina. Only authorized individuals can remove problem alligators. The possession of live alligators is also prohibited in North Carolina without a permit.

— North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission