Reuniting with History and Memory

BY Cindy Ramsey

They migrate here each spring. The lady who draws them waits patiently for their annual return. Though a quarter million others are awed by her each year she truly comes alive when her boys come home. But their numbers are diminishing. All too soon they will be extinct.

The end of an era is imminent. Not this year. Maybe not next year. But sometime in the not-too-distant future none of the boys who grew into men while manning America’s newest and fastest battleship during World War II will ever walk her decks again.

It won’t be by choice.

As the USS North Carolina Battleship celebrates her 75th birthday this year even her youngest enlisted men who are still surviving are well into their 90s. This year on Memorial Day weekend those who are able will once again make their annual trek to reunite with shipmates on their beloved ship. They will walk or roll up the gangway pause to salute the flag and cross over the threshold of their youth traveling back in memory to a time that shaped their lives on the ship that holds their hearts. The battleship carried out nine shore bombardments destroyed at least 24 enemy aircraft sank an enemy troopship and participated in every major naval offensive in the Pacific theater.

The USS North Carolina Battleship Association began in 1962 when the ship was saved from being scrapped and brought to Wilmington to become a memorial to those North Carolinians from every branch of service who died in WWII. A small delegation of shipmates and their wives dined in the Captain’s cabin as guests of the memorial’s first superintendent Rear Admiral William Maxwell. That was the first reunion.

Through hard work and perseverance those few found many more and annual reunions at the ship grew in size and significance. Shipmates who never knew each other when they served together on the North Carolina became great friends as they met and shared memories each year.

Every reunion was unique and special in its own way but some were especially memorable. Some were magical.

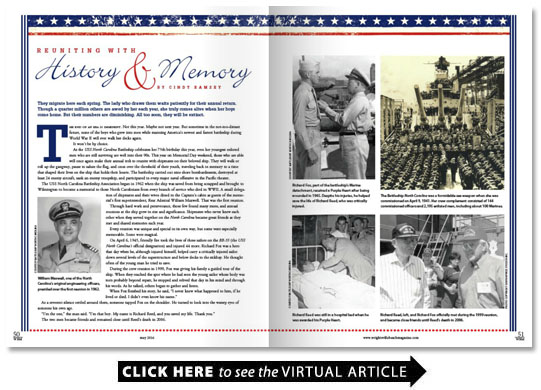

On April 6 1945 friendly fire took the lives of three sailors on the BB-55 (the USS North Carolina’s official designation) and injured 44 more. Richard Fox was a hero that day when he although injured himself helped carry a critically injured sailor down several levels of the superstructure and below decks to the sickbay. He thought often of the young man he tried to save.

During the crew reunion in 1999 Fox was giving his family a guided tour of the ship. When they reached the spot where he had seen the young sailor whose body was torn probably beyond repair he stopped and relived that day in his mind and through his words. As he talked others began to gather and listen.

When Fox finished his story he said “I never knew what happened to him if he lived or died. I didn’t even know his name.”

As a reverent silence settled around them someone tapped Fox on the shoulder. He turned to look into the watery eyes of someone his own age.

“I’m the one ” the man said. “I’m that boy. My name is Richard Reed and you saved my life. Thank you.”

The two men became friends and remained close until Reed’s death in 2006.

During the reunion in the spring of 2000 an oral history project included videotaping members of the crew. During his interview Elton Kunkle told the story of how he and the other junior officers had managed to sneak cases of liquor onto the ship when in dry dock at Pearl Harbor in early 1945. They wrapped the bottles in towels removed some plating and hid the bottles in the void next to the skin of the ship. Every night they would take a bottle out pass it around and have a little drink.

As Kunkle continued to talk battleship staff went down to the compartment where Kunkle said the liquor had been hidden. They removed the plating and found 18 bottles — still wrapped in towels. They brought one into the interview room.

Kunkle laughed and cried as he unwrapped the towel he had placed around it 55 years earlier and saw the empty bottle of Southern Comfort.

“We were putting empties back because where were we going to hide them?” Kunkle said. “Nobody believed my story but they do now.”

In 1986 four survivors of the Japanese submarine I-19 were invited to the annual reunion. They were sailors on the boat that on September 15 1942 torpedoed the North Carolina and killed five of her crew.

In preparation for the arrival of the Japanese guests the association newsletter the TARHEEL made this request of all its members who planned to attend the reunion: “Remember the I-19 men will be our guests after traveling halfway around the world just to meet with us. � Remember in 1942 they were simply doing their duty as we were and they certainly earned our respect as fighting men. � They know all too well who won the war.”

The reunion was a memorable success. The former enemies exchanged stories shared food and gifts during a picnic and honored their fallen during a joint memorial service.

During the 2008 reunion the newest ship to be named North Carolina the nuclear submarine SSN-777 was commissioned in Wilmington and crewmembers of the battleship participated in those festivities.

Crewmembers of the submarine were also special guests of the reunion events. The aged WWII sailors and the young crew of the highly sophisticated sub attended a Legacy Luncheon on the fantail of the battleship where they toasted each other shared stories and talked about their ships.

“I remember being particularly struck by the difference in both sophistication and training of the new ship’s crew as compared with what we had as much older salts ” BB-55 crewmember Bill Faulkner said. “It was pretty much on-the-job training on the battleship for sailors.”

While the sailors are the focus of and reason for the annual reunions family members attend as well. They proudly accompany their heroes and listen to their stories. Families of deceased crewmembers also find comfort and camaraderie in the gatherings.

Dave Stryker is the son of the late Rear Admiral Joe Warren Stryker who served as navigator then executive officer of the Battleship North Carolina from 1941-1944. Commander Stryker as he was known to the crew was a beloved and trusted officer.

“I treasure my many trips to the battleship crew reunions where I hear story after story about my dad ” Dave Stryker says.

Vance Velletri attended reunions with his father Fred Velletri for many years. Now he and his wife attend in his father’s memory. He recounts how important being able to visit the ship was to his father.

“In 1968 we were on our way back from a trip to Florida and he saw the sign for the ship ” Velletri says. “We got off I-95 and drove to Wilmington. We visited every couple of years and he would cry.”

They became regular attendees to the reunions and Fred Velletri was an active member of the association until his death in March 2015. He also traveled across the country dressed in his uniform and stood guard beside the caskets of his shipmates during their funerals.

Each year during the reunion a memorial service is held on the fantail of the ship. Names of each crewmember who died the previous year are read followed by the tolling of a brass ship’s bell. As the list gets shorter and the attendees fewer each year it is a stark reminder of just how few WWII veterans remain.

The memorial service is open to the public and is scheduled to take place this year on Saturday May 28 at 10 a.m.

Faulkner said one of his first impressions of the reunions was finding himself automatically reverting to that 17-year-old seaman first class when he boarded the ship. Those of the crew who attend this year’s reunion will have an opportunity to take that reversion one step further. On Sunday May 29 those who are able will man their battle stations one last time.

Nothing would thrill them more than to have visitors stop by and listen to their stories.

Saving the Ship

Each year becomes a bit more bittersweet as I attend the crew reunion of the Battleship North Carolina. So many of my special friends are gone now. I miss their excited greetings their smiles their hugs.

I first met the crew during their reunion in the spring of 2000. I spent six days helping with the oral history interviews and my life forever changed. I greeted crewmembers as they came aboard the ship and sought to persuade each one into doing an interview. Some thought they had nothing important to tell. Oh how wrong they were.

While conducting the interviews I felt as though the chair in which they sat became a time machine. I could see their expressions change as they traveled back to the days of their youth remembering both good and bad. They talked. They laughed. They cried.

At dinner one night near the end of that reunion I was internally recounting all the stories I had heard wondering how in the world I could ever find adequate words to thank them for what they endured for my freedom.

I looked up at one of the crew sitting across the table and he had tears in his eyes. I smiled at him and his next words pierced my heart.

“Thank you ” he said.

“Thank me?” I asked. “For what?”

“Thank you for saving my ship.”

I was in the third grade at Long Creek Elementary in Pender County in 1961 when children were asked to bring coins to school to help bring home the USS North Carolina. We were poor but I remember my daddy — who served in the Army in World War II — making sure we had a dime to take to school to help save the ship because it was that important.

Word had gotten around that the lady helping with the interviews had been one of the school children who took money to school to help save the ship. Many of them told me over and over again how important it was to them to be able to return to their ship every year.

I spent years interviewing the crewmembers for my book “Boys of the Battleship North Carolina” — some in person some on the phone some through letters or emails. Some became like family. My greatest hope was to do them justice in the words I would write.

During one of the reunions I purchased a Navy shirt at the annual auction and started asking crewmembers to sign the back. I have scores of signatures but very few of those who signed it are still living. I promised the men that I would wear the shirt every time I had a book signing or gave a presentation about the ship and her crew. It is my way of taking them with me wherever I go.

I always keep one other promise I made to them. They asked me to thank anyone who helped save the ship. Words cannot adequately describe the emotion they feel when they actually walk the decks of their ship return to their workstations and battle stations or touch the bunk where they slept.

So if you were one of those children who took change to school or one of the many other North Carolinians who helped save the ship and bring her to Wilmington — the crew thanks you. You have touched the hearts of the men who served aboard her and they are forever grateful.

I have been blessed to know them and call them my friends.

Cindy Ramsey is the author of Boys of the Battleship North Carolina a book that tells the story of the battleship through the eyes of the young sailors who matured into men while manning the floating fortress.