Photographs and Memories

BY Simon Gonzalez

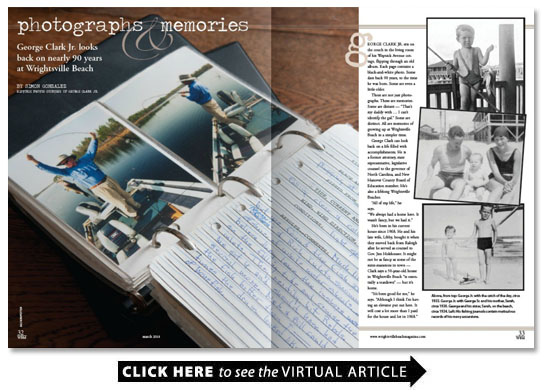

George Clark Jr. sits on the couch in the living room of his Waynick Avenue cottage flipping through an old album. Each page contains a black-and-white photo. Some date back 90 years to the time he was born. Some are even a little older.

These are not just photographs. These are memories. Some are distant — “That’s my daddy with … I can’t identify the gal.” Some are distinct. All are memories of growing up at Wrightsville Beach in a simpler time.

George Clark can look back on a life filled with accomplishments. He is a former attorney state representative legislative counsel to the governor of North Carolina and New Hanover County Board of Education member. He’s also a lifelong Wrightsville Beacher.

“All of my life ” he says. “We always had a home here. It wasn’t fancy but we had it.”

He’s been in his current house since 1968. He and his late wife Libby bought it when they moved back from Raleigh after he served as counsel to Gov. Jim Holshouser. It might not be as fancy as some of the mini-mansions in town — Clark says a 50-year-old house in Wrightsville Beach “is essentially a teardown” — but it’s home.

“It’s been good for me ” he says. “Although I think I’m having an elevator put out here. It will cost a lot more than I paid for the house and lot in 1968.”

rom the living room couch Clark enjoys a beautiful view across Waynick to Banks Channel. He can sit on his back deck and enjoy the neighborhood.

“That’s another thing about the beach ” he says. “People are so congenial. They’ll stop and talk about the flowers. Sometimes they’ll come up here and have a beer. It’s a friendly sort of situation. I enjoy it. I have a good time.”

Clark a fisherman since he was old enough to hold a rod and reel walks across the street to his 20-foot boat docked at his pier. It’s only a few steps from his back door to the beach where he can surf fish — although the aches and pains of his age keep him from doing that as much as he’d like.

The inside of the house is dominated by images. There’s a portrait of Libby over the fireplace painted by her sister Raleigh-based artist Rebecca Patman Chandler. There are his meticulously kept fishing journals with records of the ones he caught and the ones that got away complete with photos. And there are the albums with the old black-and-whites.

He opens one and sees a picture of his parents George Sr. and Sarah.

“Daddy was in the insurance business an insurance agent ” he says. “His father was a conductor on the railroad and his father was the governor of North Carolina during the first part of the Civil War. Henry Toole Clark. Mother was from Lumberton. When her nine months were up she went back to Lumberton to have me. Horace Baker the doctor was a good friend of her family. She had me in Lumberton and then came right back to Wilmington and the beach.”

Another photo shows a handsome man in uniform. It’s his father who served in World War I.

“He was in the Army ” Clark says. “He never talked about it. I understand that is normal for people that have been in combat.”

Lark leafs through more pages. He says his “89-year-old crusted-over brain” doesn’t remember all of the people and places.

“It’s just old old pictures that don’t amount to much ” he says dismissively.

One of his old courtroom opponents might leap up and object. There was no such thing as high-res images when these were taken so the quality isn’t the best and he might not recollect everybody in every picture. But they amount to a great deal.

The photos trigger memories and stories that are humorous nostalgic and unexpected. They also provide a glimpse into Wrightsville Beach history.

There’s an image of his parents’ first house at the beach an oceanfront cottage on Charlotte Street. The photo was taken shortly before the house was lost to the Great Fire of 1934 which claimed 103 buildings in less than three hours.

“That’s when my mother and father danced for joy when the house burned ” Clark says.

The fire was a tragedy for many but a godsend to the Clarks. Shifting sands had moved their house closer and closer to the ocean and it was about to go under.

“They didn’t have any rising water insurance but they had fire insurance ” he says. “The house was about to wash away. They got the fire insurance paid and they built a new house.”

He points to an image of the new house. This one lasted 20 years until Hurricane Hazel knocked it down.

“In those days almost no one lived at the beach year round ” he says. “They had a little old cottage and they stayed there in the summer and in Wilmington in the winter.”

A picture of his sister Sarah who is three years younger elicits a chuckle.

“A great story about her ” he says. “During the Depression one time my mother and father took us out on the beach to have a picnic. Daddy had spent a lot of money getting steak. We had a fire and daddy was grilling the steak. He poured salt in his hand and sprinkled the salt on the steak. My sister saw him do that and she picked up a handful of sand and sprinkled it on the steak. I can see Daddy right now. He stuck a fork in it and ran out in the surf to wash it off.”

A photo of a woman and a child on the trolley track triggers a memory of how most visitors arrived for a day at the seaside. The cars in the pictures mostly belong to residents who parked on sandy roads then got around on raised boardwalks.

“Everything was connected by boardwalks ” he says. “There was no concrete or asphalt anywhere. In front of our beach cottage the one that we built after the fire there was a raised boardwalk I would say it was raised an average of 5 feet that went all the way from Birmingham Street to Asheville Street. About seven blocks. The water came up under it at high tide.”

The boardwalks only live on in the photos. And so does a Wrightsville Beach amusement.

“Daddy had a putt-putt back then. Is that what you call it?” he says. “It was behind the Seashore Hotel which is where the Blockade Runner is now.”

His father’s mini-golf venture reminds Clark of other ways to pass the time.

“We spent a lot of time at Joe Stone’s Bowling Alley which is where the Neptune parking lot is now ” he says. “It was very popular. We didn’t spend much time at Lumina at least I didn’t and my neighbors didn’t. It was primarily a bathhouse. Men and women could come and rent bathing suits or change shower things like that. That wasn’t anything we needed. Although we did go when big bands were there. I saw several of them. I remember Jimmie Lunceford particularly. Cab Calloway I remember. Jimmy Dorsey. I don’t believe Tommy Dorsey ever came here but Jimmy Dorsey did. I had to sneak in to one or two of those. We couldn’t afford to pay for it but we had ways of sneaking in.”

There are lots of photos of young George in and around the ocean.

“I spent an awful lot of time in the water ” he says. “That included the ocean and the sound. I particularly remember when you swam in the sound you never did it at low tide. A lot of sewage dumped into the sound in those days. You waited for high tide.”

Fishing is another recurring theme. There are lots of photos of Clark with a rod in his hand beginning when he was practically a toddler.

“I did a lot of fishing ” he says. “In those days there were jetties. Jetties have barnacles and the sheepshead love to eat barnacles off the jetties. And so we did a lot of casting to the jetties using what we called sea fleas. Little things about the size of your thumb. We had a lot of luck catching rather large sheepshead. I used to do a lot of surf fishing. In the old days you could stand on the beach and cast a weighted treble hook and catch mullet that way. In September you could go out there and catch a mess of bluefish.”

A photo of a rowboat on a wheeled cart is a reminder that everybody could catch a mess of just about everything back then. The rowboats towed seines weighted fishing nets that hung vertically in the water.

“That’s something you don’t see anymore around here ” he says. “About late August and into September there were at least two and maybe three long-haul seining companies. Johnnie Mercer had one Walter Stokley had one and I believe the Robinsons at Lumina had one. In those days you would see acres and acres of popeye mullet swimming from north to south one right after another. Those seiners would drop one end of the net on the beach and then row around the school of mullet and come back in on the other side of them making a big U and corralling them and then pulling in both ends of the net to pull them up on the beach. I remember one time Johnnie Mercer pulled in a school that weighed 52 000 pounds. At least that’s my recollection.”

Fish weren’t the only plentiful marine life back then.

“I remember also you could go anywhere in the waters behind the beach and throw out a line with a chicken neck on it and get a mess of blue claw crabs ” he says.

Crabbing and fishing weren’t just for recreation when Clark was a boy. They were done out of necessity.

“Crabbing was very popular particularly in the early days which was part of the Depression ” he says. “You ate a lot of fish you ate a lot of crabs. And another thing in the early days there were the folks who caught shrimp on the sound and walked down the beach with baskets of them selling them. They did the same with pigfish and blackfish that they caught by rowing out into the ocean. Others had carts they pushed up and down the beach selling fresh vegetables. This was in the days before refrigeration or before really good refrigeration. You had iceboxes and trucks that came by daily with great big blocks of ice that you put in your icebox.”

Clark is quick to dismiss some pictures like the one of him as a child scrunched up in a white enamel basin.

“That’s not worth anything but that’s me taking a bath ” he says.

The tub is outside on a boardwalk running next to the house. It isn’t connected to plumbing and it triggers a memory of a time before taking a hot shower was simply a matter of turning a tap.

“I remember that to get hot water we and I think most people had a gas-operated hot water heater ” he says. “So if you wanted to take a hot shower you turned the gas on and heated the water that way.”

A conversation about water brings up a not-so-pleasant recollection.

“Another thing that is unforgettable is the water at the beach ” he says. “It smelled like rotten eggs. It stunk and a lot of people wouldn’t drink it. A lot of people wouldn’t take showers in it because it smelled so bad. For that reason we had a company called Greenfield Water Company which brought spring water from Greenfield Lake in 5-gallon and 1-gallon jugs that they sold all up and down the beach.”

A photo from 1946 shows Clark sitting in a lifeguard stand shortly after he graduated from New Hanover High School. It was a natural job for someone who grew up around the ocean — even if it wasn’t as exciting as he expected.

“Lifeguarding wasn’t as glamorous as it is thought to be ” he says. “It is probably the most boring job in the world. Because you are not even supposed to be reading. You are supposed to be looking and that is not much fun. The lifeguards in those days as I specifically recall we worked for the police department. There were no necessary qualifications. No one had to have first aid experience or classes or anything like that. In addition we had no supervision. We came to work when we were supposed to and nobody checked on that or checked when we left. And if it was raining we went home. But in spite of the looseness we never had a drowning at any place on the beach that had a lifeguard stand. I think that’s remarkable. That doesn’t mean that we didn’t pull a lot of people out of the surf because we did. I remember one Fourth of July we pulled 30-something people off of the jetty at Birmingham Street.”

The jetty he recalls was right behind Charlie Roberts’ grocery story.

“I distinctly remember Robert’s Grocery ” he says. “I remember Charlie Roberts I knew him. I knew his wife Dorothy. The story is that Charlie when he got sick Dorothy was a nurse and she took care of him. He said ‘If I get out of here I want you to be my wife.’ She said ‘OK ‘ and they did. They were very successful as a husband and wife and as grocers.”

Other old Wrightsville Beach and Wilmington names fall readily off his tongue: Bellamy. Murchison. Wise. Corbett. Bill Blair father of the current mayor. Johnnie Mercer namesake of the iconic pier. Lawrence Lewis who built the Blockade Runner. Bill Creasy.

Looking through the album takes Clark on a journey through the past but he still thinks of the future.

“I was born May 19 1928 ” he says. “With any luck at all I’ll get to be 90 come May. I’ve had a lot of luck so far.”

The present isn’t so bad either. He has a new girlfriend. He looks forward to visits from his sons and grandchildren. And he still fishes regularly going out in his bass boat a couple of times a week.

“I’m so lucky ” he says.