J is for Jam

BY Colleen Thompson

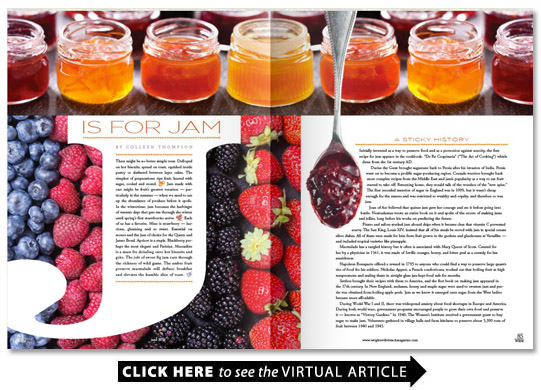

There might be no better simple treat. Dolloped on hot biscuits spread on toast squished inside pastry or slathered between layer cakes. The simplest of preparations: ripe fruit heated with sugar cooled and stored.

Jam made with care might be fruit’s greatest vocation — particularly in the summer — when we need to use up the abundance of produce before it spoils. In the wintertime jam becomes the harbinger of warmer days that gets me through the winter until spring’s first strawberries arrive.

Each of us has a favorite. Mine is strawberry — luscious gleaming and so sweet. Essential on scones and the jam of choice for the Queen and James Bond. Apricot is a staple. Blackberry perhaps the most elegant and Parisian. Muscadine is a must for drizzling onto hot biscuits and grits. The jolt of sweet fig jam cuts through the richness of wild game. The amber fruit preserve marmalade still defines breakfast and elevates the humble slice of toast.

A Sticky History

Initially invented as a way to preserve food and as a protection against scarcity the first recipe for jam appears in the cookbook: “De Re Coquinaria” (“The Art of Cooking”) which dates from the 1st century AD.

Darius the Great brought sugarcane back to Persia after his invasion of India. Persia went on to become a prolific sugar-producing region. Crusade warriors brought back more complex recipes from the Middle East and jam’s popularity as a way to eat fruit started to take off. Returning home they would talk of the wonders of the “new spice.” The first recorded mention of sugar in England was in 1099 but it wasn’t cheap enough for the masses and was restricted to wealthy and royalty and therefore so was jam.

Joan of Arc believed that quince jam gave her courage and ate it before going into battle. Nostradamus wrote an entire book on it and spoke of the secrets of making jams and jellies long before his works on predicting the future.

Pirates and sailors stocked jam aboard ships when it became clear that vitamin C prevented scurvy. The Sun King Louis XIV insisted that all of his meals be served with jam in special ornate silver dishes. All of them were made for him from fruit grown in the gardens and glasshouses at Versailles — and included tropical varieties like pineapple.

Marmalade has a tangled history but it often is associated with Mary Queen of Scots. Created for her by a physician in 1561 it was made of Seville oranges honey and bitter peel as a remedy for her seasickness.

Napoleon Bonaparte offered a reward in 1795 to anyone who could find a way to preserve large quantities of food for his soldiers. Nicholas Appert a French confectioner worked out that boiling fruit at high temperatures and sealing them in airtight glass jars kept food safe for months.

Settlers brought their recipes with them to America and the first book on making jam appeared in the 17th century. In New England molasses honey and maple sugar were used to sweeten jam and pectin was obtained from boiling apple peels. Jam as we know it emerged once sugar from the West Indies became more affordable.

During World War I and II there was widespread anxiety about food shortages in Europe and America. During both world wars government programs encouraged people to grow their own food and preserve it — known as “Victory Gardens.” In 1940 The Women’s Institute received a government grant to buy sugar to make jam. Volunteers gathered in village halls and farm kitchens to preserve about 5 300 tons of fruit between 1940 and 1945.

Revivalist Fervor

As with many artisan food trends that were once a necessity long ago — something your grandma used to do — they have become litmus tests for foodies. Preserving food at home has seen a revival as lushly photographed cookbooks like “Jamit Pickle Cure It ” have hit bookshelves. An endless stream of blog posts also touts the virtues of jam-making. Celebrities have joined the throngs of enthusiasts too. Supermodel Kate Moss recently made jam and sold it at the Glastonbury Festival for charity; Taylor Swift gives it as gifts to friends and family; Khloe Kardashian prepared strawberry and vanilla bean jam and posted the entire spectacle on Snapchat. Sales of jam-making paraphernalia have soared: Bell Mason jars jam thermometers and muslin squares.

The fastest growing sector of the market however is savory jams made from produce like tomatoes onions peppers chili ginger and even bacon. Hot pepper jam has always been a Southern staple but recently savory jams overtook sriracha as the fastest-growing condiment according to market research company Datassential. Marisa McClellan author of “Food in Jars” is perhaps one of savory jam’s biggest enthusiasts. “I’m always looking at ways to open people’s eyes to the different opportunities in preserve-making ” says McClellan. “One of these things is savory jam.”

Recipe Basics

1 pound fruit

1 pound granulated sugar

lemon juice

Buying jam gives no way near the satisfaction of making it yourself and it does not have to be an intimidating exercise. Jam recipes often comprise equal weights of fruit and sugar. The ripe fruit is simply chopped into pieces placed in a heavy-bottom pot and crushed to release the juice. Add sugar and the juice of fresh lemon to brighten the fruit through all that sugar and help it set. Bring the mixture to a boil once the jam thickens let it sit for 20 minutes then ladle into sterilized jars filling to just below the top.

The 1:1 ratio can be played with but the preserving effect might be lost if too much fruit is used; if too much sugar is used it will crystallize. Time is the secret ingredient to making jam without pectin; both the fruit and sugar need plenty of it to cook and thicken. Simmering the jam slowly will drive out moisture from the fruit and help to preserve and thicken it. Water content will vary in all fruit and some fruits might take longer to set. The choice of fruit for jam is almost endless but make sure to use seasonal slightly unripe fruit as it contains more pectin and is slightly more acidic which will add body and structure to your jam.

What’s the difference? kind of the same but not really…

Jellies are made only from fruit juice; the solids are strained from the juice before the sugar is added making it relatively translucent and easy to spread.

Jams are chunks of fruit crushed together and boiled until soft — the chunks are left in the mixture so the result is not a clear spread.

Marmalades are jellies in which pieces of fruit and rind are suspended not crushed.

Preserves are similar to jams with larger chunks and can be a mixture of fruits with nuts and raisins often added.