Hot August Eve

BY Amy Kilgore Mangus

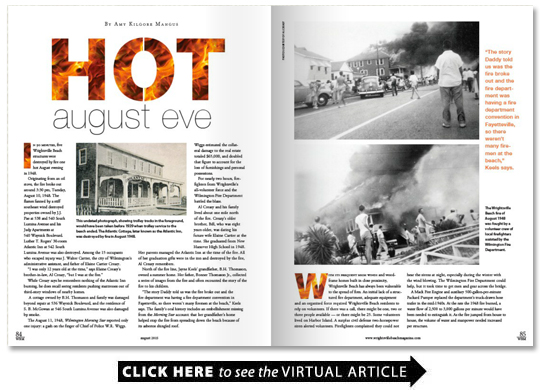

In 90 minutes five Wrightsville Beach structures were destroyed by fire one hot August evening in 1948.

Originating from an oil stove the fire broke out around 3:30 pm Tuesday August 10 1948. The flames fanned by a stiff southeast wind destroyed properties owned by J.J. Pae at 538 and 540 South Lumina Avenue and his Judy Apartments at 540 Waynick Boulevard. Luther T. Rogers’ 30-room Atlantic Inn at 542 South Lumina Avenue was also destroyed. Among the 15 occupants who escaped injury was J. Walter Cartier the city of Wilmington’s administrative assistant and father of Elaine Cartier Creasy.

“I was only 12 years old at the time ” says Elaine Creasy’s brother-in-law Al Creasy “but I was at the fire.”

While Creasy says he remembers nothing of the Atlantic Inn burning he does recall seeing residents pushing mattresses out of third-story windows of nearby homes.

A cottage owned by B.H. Thomason and family was damaged beyond repair at 536 Waynick Boulevard and the residence of S. B. McGowan at 546 South Lumina Avenue was also damaged by smoke.

The August 11 1948 Wilmington Morning Star reported only one injury: a gash on the finger of Chief of Police W.R. Wiggs. Wiggs estimated the collateral damage to the real estate totaled $65 000 and doubled that figure to account for the loss of furnishings and personal possessions.

For nearly two hours firefighters from Wrightsville’s all-volunteer force and the Wilmington Fire Department battled the blaze.

Al Creasy and his family lived about one mile north of the fire. Creasy’s older brother Bill who was eight years older was dating his future wife Elaine Cartier at the time. She graduated from New Hanover High School in 1948. Her parents managed the Atlantic Inn at the time of the fire. All of her graduation gifts were in the inn and destroyed by the fire Al Creasy remembers.

North of the fire line Jayne Keels’ grandfather B.H. Thomason owned a summer home. Her father Bonner Thomason Jr. collected a series of images from the fire and often recounted the story of the fire to his children.

“The story Daddy told us was the fire broke out and the fire department was having a fire department convention in Fayetteville so there weren’t many firemen at the beach ” Keels says. The family’s oral history includes an embellishment missing from the Morning Star account: that her grandfather’s home helped stop the fire from spreading down the beach because of its asbestos shingled roof.

ith its frequent high winds and wood-frame homes built in close proximity Wrightsville Beach has always been vulnerable to the spread of fires. An initial lack of a structured fire department adequate equipment

and an organized force required Wrightsville Beach residents to rely on volunteers. If there was a call there might be one two or three people available — or there might be 25. Some volunteers lived on Harbor Island. A surplus civil defense two-horsepower siren alerted volunteers. Firefighters complained they could not hear the sirens at night especially during the winter with the wind blowing. The Wilmington Fire Department could help but it took time to get men and gear across the bridge.

A Mack Fire Engine and auxiliary 500-gallon-per-minute Packard Pumper replaced the department’s truck-drawn hose trailer in the mid-1940s. At the rate the 1948 fire burned a water flow of 2 500 to 3 000 gallons per minute would have been needed to extinguish it. As the fire jumped from house to house the volume of water and manpower needed increased per structure.

On this day there also was apparently delay in getting water on the fire ” says the town’s first paid firefighter former chief

Everett Ward. “I think the fire was burning out of control. It hopped from one building to the next ? not enough water and not enough manpower.”

Once the truck and crew arrived on the scene water was pulled from Banks Channel using fire ramps — slopes leading to the water where a fire engine could use its hard rubber suction to draft water from the surface.

Ward says town officials just did not know they were operating the fire department archaically.

“They never thought about things like required fire flows how many people are really necessary how many trucks do we really need to suppress fire what’s it gonna cost ” Ward says.

This fire among five others in the 1940s led to numerous town meeting discussions about hiring firefighters to operate equipment and arrive on scene in a timely manner.

“They had a nervous itch about fires ” Ward says. “The fires didn’t occur frequently but with enough frequency to keep them alert to their vulnerability.”

This discussion would lead to the evolution of the Wrightsville Beach Fire Department protocol by which police dispatchers took calls and responded with equipment meeting volunteers often retired Wilmington firefighters on scene. The department also began completing a two-page list of improvements suggested by the Insurance Service Office (ISO). The ISO bases its ratings on periodic visits to fire departments where manpower level of training equipment availability of water and dispatching capabilities are assessed. The lower the number the better the rating.

“The department was deficient ” Ward says. “At the time the Fire Suppression Rating Schedule was a ten. They went to an eight after they got new water mains in after the war.”

The department under his direction “took the list and began checking it off ” Ward says. It went from an eight to a six because it was keeping better records and ultimately improved the fire rating to a four “where it remains today ” he says.

Many changes have been made to the Wrightsville Beach Fire Department since it formed in 1915. It evolved from an on-call volunteer group that employed carts bucket brigades and existing water pipes — because there were no fire hydrants — to battle the Great Fire of 1934 into a combination professional and volunteer force that responds in minutes with three fire engines capable of pumping 4 500 gallons of water onto a fire in one minute. Technology like thermal imaging cameras has significantly improved the department’s ability to extinguish a fire while protective gear and use of self-contained breathing apparatus as an example have improved the department’s ability to protect the firefighting men and women.

The changes though are not all about the equipment or even the state-of-the-art public safety facility on Bob Sawyer Drive completed September 2010.

Three components make up the Wrightsville Beach Fire Department: 12 career personnel 25 paid on call members and the department’s intern program.

“We are one department made up of many pieces which functions as a team to get the job done. We pride ourselves on that ” says Fire Chief Frank Smith who comes from a long line of firefighters with a career firefighting grandfather and a father and uncle who were volunteers. Smith joined the department as a volunteer in February 1987 and succeeded Ward as chief in 2003.

Ret. Wrightsville Beach Fire Chief Everett Ward joined the all-volunteer department in January 1973. He was elected chief in 1984 making him the first paid employee. Ward retired after 30 years of service in 2003.

The WBFD observed its centennial anniversary July 28 2015.