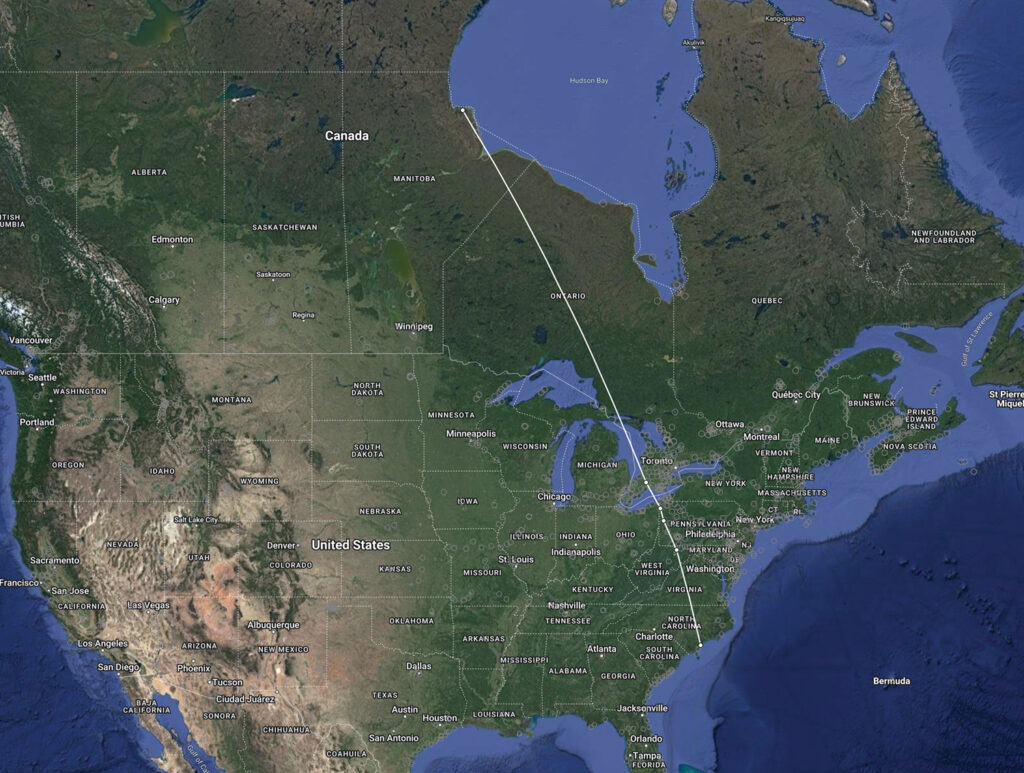

Walking a coastal barrier island at the end of July 2022, a visitor near the mud flats notices a plump little bird with a long beak and short legs. When the shorebird scurries away, the human gives it no more thought. It is doubtful they knew this was a short-billed dowitcher, which had flown 2,000 miles to the North Carolina coast from where it was tagged by biologists just a month prior in the boreal wetlands of Hudson Bay, near Churchill, Canada.

This little shorebird and two others were tracked as they migrated to Lea Island in Southeastern North Carolina, just south of Topsail Island. The island is part of Audubon North Carolina’s coastal sanctuary network and an officially designated important bird area. Its naturally occurring inlets and mudflats are good forging grounds for migrating species including these long-traveled dowitchers.

The dowitchers’ journey was tracked by a new Motus tower — the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international collaborative research network that uses coordinated automative radio telemetry — installed in the spring. The birds were radio-tagged near where they nested within 800 yards of each other in Canada, then over a few days they traveled separately cross-country to the undeveloped barrier island. The birds, detected on different dates along the way, followed the same path. A fourth tagged dowitcher was detected at Masonboro Island, 15 miles south of Lea Island.

The birds were fitted with nanotags in June. The tiny radio tracking devices weigh as little as an aspirin and are an alternative to the heavier satellite radio transmitters placed on larger birds like hawks and owls. The data collected is shedding light on patterns of migration among what Audubon describes as an under-studied shorebird.

The solar powered 20-foot high Motus tower was installed on Lea Island as a partnership between Audubon North Carolina, Cape Fear Audubon Society and the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Danner Research and Teaching Lab. Towers on Bald Head Island and Masonboro Island were installed by the North Carolina Coastal Reserve and the Bald Head Island Conservancy in partnership with the Danner Lab to further help detect migration in the Cape Fear region.

Under the leadership of Dr. Ray Danner, assistant professor of evolutionary ecology and part of the Department of Biology and Marine Biology, the Danner Lab focuses mainly on coastal birds that nest on the beaches and marsh.

The towers pick up radio signals from any tagged bird that flies within nine miles. The data is received by a ground-based transmitter instead of an orbiting satellite, and is uploaded automatically to the internet where it can be studied and made available to the public. The towers are part of a global network that is giving fresh insights into the movements of birds making voyages from Canada all the way to Argentina. The real-time data is made available via a free Audubon app so users can view the migrating birds that pass by.