Ghost Trees

BY Andy Wood

Inexorable adj. not capable of being moved by entreaty: unyielding.

Ghost n. a faint weak or greatly reduced appearance trace or possibility of something.

The Cape Fear River North Carolinas largest river basin stretches across more than 9 000 square miles of North Carolinas landscape. It begins as a network of swampy streams in the piedmont area of Greensboro and grows with water from hundreds of tributaries that drain surrounding lands then discharges its contents into the Atlantic Ocean about 20 miles south of Wilmington; the last of several major towns and cities that draw water from the river.

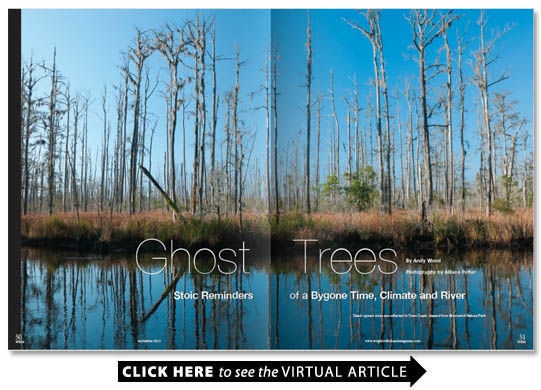

In recent years observers in lower reaches of the Cape Fear River including its tributaries have witnessed a disquieting condition among trees that once thrived in and around this great rivers waters: Many of the once lush cypress tupelo and other swamp trees are dead and still more are presently dying. Its not a new situation but the breadth and scope of dead trees many within sight of busy highways has caught public attention and earned the stark wooden skeletons the moniker Ghost Trees.

In truth most of the Cape Fears ghost trees seen by passersby are the remains of baldcypress Taxodium distichum a decay-resistant plant specially adapted to growing in freshwater wetland environs including the swamp forests found adjacent to the Cape Fear River and its tributaries.

A native of the American Southeast baldcypress are conifer trees related to the famous redwood trees of the Pacific Northwest. Like their redwood cousins baldcypress are long-lived trees as evidenced by several still living today in a swamp on the Black River a tributary to the Cape Fear River that are estimated to be more than 1 700 years old.

Baldcypress wood is renowned and prized for its decay resistance and many of the ghost trees seen along the Cape Fear Rivers shoreline have been standing dead for decades. Living or dead baldcypress trees provide habitat value to wildlife. While cypress wood is decay resistant the trunks of old-growth living trees are often hollow which creates shelter for cavity-dwelling animals including woodpeckers bats and tree frogs among other species. Trees with a diameter of four to five feet may disguise a hollowed center spacious enough to shelter adult black bears.

Baldcypress are adapted to life in a wet environment specifically freshwater wetlands including riverine swamps. For reasons not fully understood baldcypress trees produce from their roots odd-shaped stumps called knees. Cypress knees can grow up to five feet tall depending on water conditions and may provide structural support for the trees with roots that must remain close to the swamp soil surface to avoid suffocating from lack of oxygen under stagnant water. Cypress knees may also serve as mechanisms for gas exchange carrying oxygen from air to roots submerged in low-oxygenated water and soil.

While the exact role of cypress knees may be debated we know with certainty that in addition to contributing to biological diversity baldcypress and other swamp trees and plants perform ecosystem services to our benefit including water storage cycling and filtration; services we cannot easily replicate through engineering let alone for free as swamps provide. This brings us back to the ghost trees haunting the lower reaches of the Cape Fear River and its tributaries.

Cape Fears ghost trees are silent reminders of a bygone era a bygone climate and a bygone river. The ghost trees we see throughout the Cape Fears lower reaches died as a result of saltwater intrusion that proved toxic for the freshwater trees and the habitats they once helped support. Saltwater continues to flood into and up the Cape Fear River just as it has done for thousands of years. What is different today from millennia ago is the increased rate at which salty water is drowning the Cape Fear River; a rate hastened by the engineered deepening of the rivers connection to the ocean.

To understand how Cape Fears ghost trees came to be we must delve into history geologic and human. Geologically the Cape Fear coast has been changing since the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) the period of Earths past 25 000 to 18 000 years before present when much of North America was frozen beneath two miles of ice and snow and the global ocean was 400 feet lower than today. Beginning about 18 000 years ago our worlds climate warmed rapidly as it entered the interglacial period we are now experiencing. The interglacial warming turned glaciers into meltwater that flowed into the ocean raising sea level and drowning coastlines as water crept inland.

If we could visit southeastern North Carolina 10 000 years before present we would find the Cape Fear River generally flowing where it is today though its mouth would meet the ocean at a point several miles east of Bald Head Island the fringing point of land on the east corner of the rivers present day mouth. Ten thousand years ago Bald Head was not yet an island; it was part of the continental mainland a realm then covered by swamp forest and hardwood and conifer trees more similar to present-day conditions far to the north.

Fast forward to 3 000 years before present to find this region in a condition very much like the first colonists described. Bald Head Masonboro Wrightsville Beach Figure Eight and North Carolinas other present-day barrier islands were relatively young features in generally the location they now occupy and the Cape Fear River flowed freshwater directly into the ocean with bald- cypress swamps and water lilies fringing its shoreline all the way to what is now Southport North Carolina.

The early 1700s would see rapid changes on the landscape including swamps converted to rice plantations along the lower reaches of the Cape Fear River especially in Brunswick County above and below Town Creek. Other changes included clearing and deepening the Cape Fears main channel to facilitate shipping traffic on the river. This is where the story of the ghost trees gets complicated.

For dozens of centuries a rising ocean flooded onto the offshore zone we call the Continental Shelf where once the Cape Fear and other coastal plain rivers flowed in a meandering course to an ocean many miles from its current shoreline about 60 miles from the mouth of todays Cape Fear. Through past millennia the rising sea flooded and drowned North Carolinas rivers and swamps along with the terrestrial grassland and woodland habitats that once supported giant mammals including now-extinct mammoths in addition to many smaller animals we still see today.

The offshore stumps of ghost trees are evidence of coastal changes from a long since risen sea. But upstream of the ocean along the shorelines of a brackish Cape Fear River and its tributaries ghost trees provide evidence of more recent history as unintended victims of human activity that includes deepening a freshwater river to a saltwater sea. Snagging old logs and channelizing the Cape Fear River during the past 200 years has allowed ever-larger ships to slip upstream to Wilmington but these activities also enabled saltwater from the Atlantic Ocean to slip upstream in the process converting what was once freshwater swamp and marsh into what is now a wide and productive brackish estuary complete with grassy saltmarshes and tidal creeks harboring blue crabs shrimp and many kinds of saltwater fishes of commercial recreational and ecological value.

Researchers are piecing together the history of the relatively recent geologic past with help from stumps and logs of bygone forests observed on the North Atlantic seafloor near Denmark the Gulf of Mexico seafloor off the coast of Alabama and the slanted continental seafloor off the North Carolina coast. The historic path of the Cape Fears now drowned river channel is evidenced by remains of tree stumps standing ghost-like on a seafloor now submerged beneath the waves of an inexorably rising sea.