www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com 35

WBM

Rivenbark described that film as “pretty much a

novelty” at the Hall, perhaps because there was more

money in bringing in plays or because the theater was

too big for showing movies to be economically viable.

But Thalian refused to be left out of the nation’s grow-ing

fascination with the silver screen. Birth of a Nation

was shown, accompanied by a full orchestra, and

during the 1930s Shirley Temple movies were popular.

The history of movies at Thalian illustrates a surpris-ing

fact. While outward forms may change, the essence

of theatrical entertainments often remains remarkably

the same. Lecturers, for example, attracted large crowds

during the Hall’s early years. One of the most popular

was Oscar Wilde, who spoke on aesthetics and his

theory of beauty. Temperance lectures were another big

draw during Thalian’s early years.

Japanese acrobats, who were declared “the most

wonderful jugglers in the world” when they performed

at Thalian in 1867, were replaced in the 21st century by

the stylized and athletic performance of the Shanghai

Huai Opera, which performed in 2009.

Musical performances have proven to be a remark-ably

consistent part of Thalian’s history. Opera

companies, as well as individual singers, visited with

regularity, and operettas enjoyed wide acclaim. All

kinds of vocal and instrumental groups have performed

at Thalian, from all-female cornet bands to John

Phillip Sousa, and from symphony orchestras to the

U.S. Marine band. As with movies, many concerts

have moved to more specialized venues, but a variety of

musical acts continue to appear. The Hall has show-cased

classical pianists, jazz trios and even an African a

cappella group.

THALIAN Hall was certainly segregated even though

the city was one of the most integrated towns around.

But Rivenbark believed that economics became the

deciding factor. “In the end,” Rivenbark said, “it’s all

about making money and selling tickets.”

When artists appeared who appealed primarily to a black audi-ence,

Rivenbark believed that “they would put all the black people

downstairs and put the white people in the balcony.” When Booker

T. Washington spoke in 1910, “they

basically divided the house in half;

it had a center aisle, so they put the

blacks on one side and the whites on

the other,” Rivenbark said.

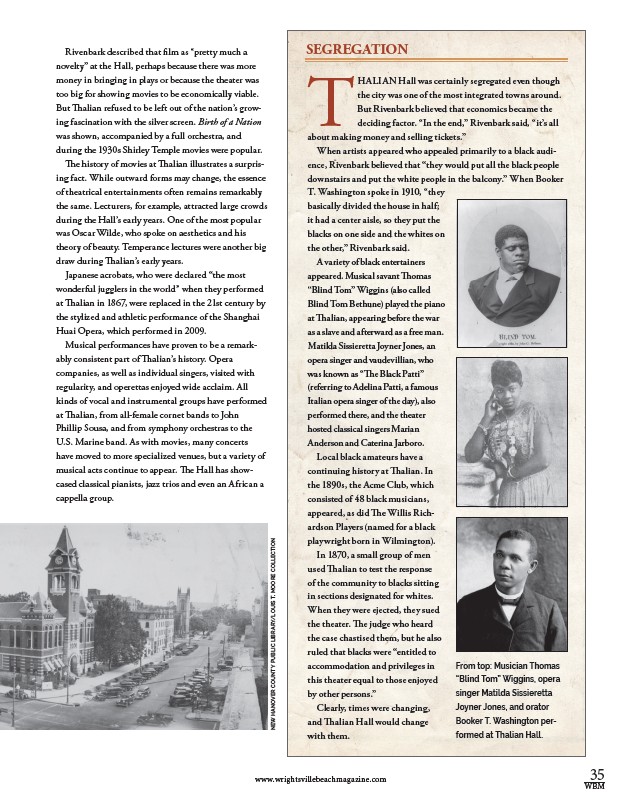

A variety of black entertainers

appeared. Musical savant Thomas

“Blind Tom” Wiggins (also called

Blind Tom Bethune) played the piano

at Thalian, appearing before the war

as a slave and afterward as a free man.

Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, an

opera singer and vaudevillian, who

was known as “The Black Patti”

(referring to Adelina Patti, a famous

Italian opera singer of the day), also

performed there, and the theater

hosted classical singers Marian

Anderson and Caterina Jarboro.

Local black amateurs have a

continuing history at Thalian. In

the 1890s, the Acme Club, which

consisted of 48 black musicians,

appeared, as did The Willis Rich-ardson

Players (named for a black

playwright born in Wilmington).

In 1870, a small group of men

used Thalian to test the response

of the community to blacks sitting

in sections designated for whites.

When they were ejected, they sued

the theater. The judge who heard

the case chastised them, but he also

ruled that blacks were “entitled to

accommodation and privileges in

this theater equal to those enjoyed

by other persons.”

Clearly, times were changing,

and Thalian Hall would change

with them.

From top: Musician Thomas

“Blind Tom” Wiggins, opera

singer Matilda Sissieretta

Joyner Jones, and orator

Booker T. Washington per-formed

at Thalian Hall.

SEGREGATION

NEW HANOVER COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY/LOUIS T. MOORE COLLECTION