IT was turkey season, and I was returning home

from a scouting trip driving through one of

those lonely, almost-abandoned Southern mill

towns. The main street looked like something

z

from an old Western movie — a place once thriving,

now lost in time.

On the roadside, a tanned and weathered farmer in

faded coveralls stood beside his vintage truck. The hood

was up; it was a cold morning and there were no cars

passing by. Nothing was open in the town, and no garage

or station had survived there anyway.

I stopped and offered to help. He asked if I might take

him to his farm not too far away. He would retrieve the

truck later, he said.

There was only one road leading into the farm — a

narrow dirt track lined with a canopy of oak and hickory,

washed over in places by a bordering creek, and just wide

enough for my truck to pass through. Three hens and a

big tom scurried down the road ahead and then melted

back into the forest.

The farmhouse was small but friendly, the yard trim

and neat with beds of daffodils and hyacinths popping

up here and there. An old Farmall 230 tractor stood

under a tin shed. A big rooster and several chickens

pecked and scratched under a scuppernong vine.

The farmer tried to pay me, but I said I was happy to

help. I asked if he allowed turkey hunting. He said he’d

seen some turkeys in a 20-acre peanut field down by the

river. If I was so inclined, I could hunt there away from

the house. He motioned me back to my truck to show me

the way.

We drove along fields, hedgerows, and finally through

a wall of sumac and catclaw brier that opened suddenly

into the field. It was small and peaceful, framed on one

side by a languid river. Legions of bald cypress towered

above its banks and leaves spun slowly downstream in a

molasses current.

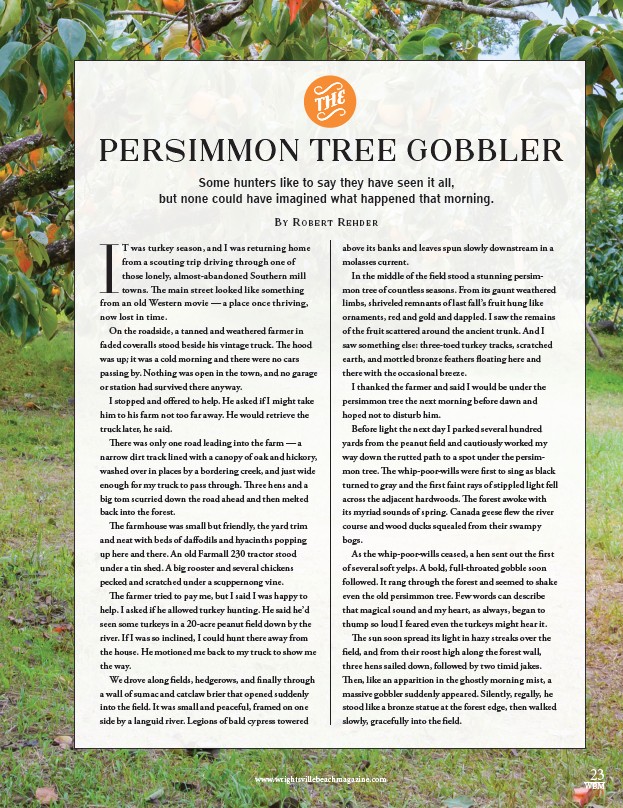

In the middle of the field stood a stunning persim-mon

tree of countless seasons. From its gaunt weathered

limbs, shriveled remnants of last fall’s fruit hung like

ornaments, red and gold and dappled. I saw the remains

of the fruit scattered around the ancient trunk. And I

saw something else: three-toed turkey tracks, scratched

earth, and mottled bronze feathers floating here and

there with the occasional breeze.

I thanked the farmer and said I would be under the

persimmon tree the next morning before dawn and

hoped not to disturb him.

Before light the next day I parked several hundred

yards from the peanut field and cautiously worked my

way down the rutted path to a spot under the persim-mon

tree. The whip-poor-wills were first to sing as black

turned to gray and the first faint rays of stippled light fell

across the adjacent hardwoods. The forest awoke with

its myriad sounds of spring. Canada geese flew the river

course and wood ducks squealed from their swampy

bogs.

As the whip-poor-wills ceased, a hen sent out the first

of several soft yelps. A bold, full-throated gobble soon

followed. It rang through the forest and seemed to shake

even the old persimmon tree. Few words can describe

that magical sound and my heart, as always, began to

thump so loud I feared even the turkeys might hear it.

The sun soon spread its light in hazy streaks over the

field, and from their roost high along the forest wall,

three hens sailed down, followed by two timid jakes.

Then, like an apparition in the ghostly morning mist, a

massive gobbler suddenly appeared. Silently, regally, he

stood like a bronze statue at the forest edge, then walked

slowly, gracefully into the field.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com 23

WBM

Persimmon Tree Gobbler

Some hunters like to say they have seen it all,

but none could have imagined what happened that morning.

By Ro b e r t Re h d e r